ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

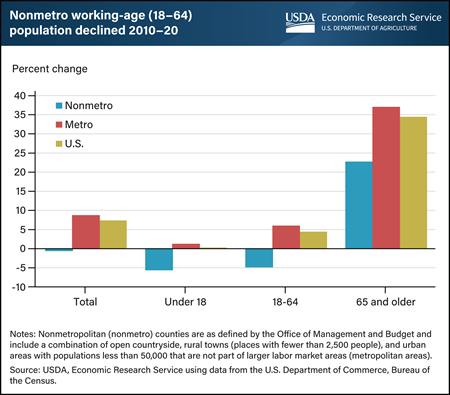

In nonmetro areas from 2010 to 2020, the working-age population (ages 18 to 64) declined by 4.9 percent, and the population under age 18 declined by 5.7 percent. At the same time, the population of those 65 years and older grew by 22 percent. In metro areas, the working-age population increased by 6 percent during the 2010s; however, this growth was overshadowed by the 37 percent growth in the 65 and older population. Nationwide, the overall U.S. population has aged as the baby boomer generation entered their 60s and 70s. Nonmetro areas, in addition to having an aging population, also face population decline. Between 2010 and 2020, U.S. Census data show the population in nonmetro counties declined by 0.6 percent, the first decade of overall nonmetro population decline in U.S. census history. Nonmetro population subsequently increased in the first year and a half of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from 2020 to 2021 which saw people move out of metro areas into rural places. However, population gains due to COVID-19 were not enough to offset a decade-long slide in the share of the population that is of working-age nor to reduce the share of the rural population that was 65 or older during this period. Overall, population decline and an increase in average age in rural areas will affect the makeup and availability of the rural labor force. This chart appears in the USDA, Economic Research Service report Rural America at a Glance: 2022 edition, published on November 15, 2022.

Thursday, November 10, 2022

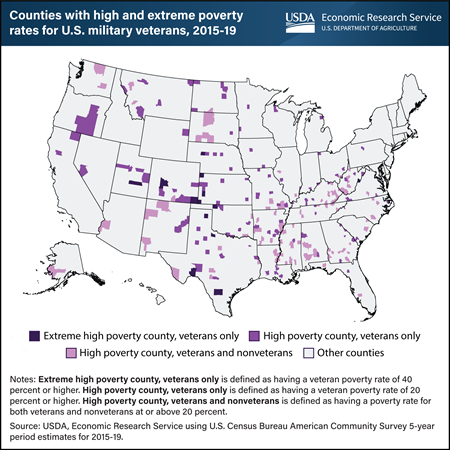

USDA, Economic Research Service’s (ERS) analysis of the American Community Survey estimates for 2015–19 reveal the poverty rate for veterans to be nearly 5 percentage points lower than for non-veteran adults (8.2 percent compared to 12.8 percent). However, in many areas of the nation, veterans have higher poverty rates than nonveterans, especially in nonmetropolitan counties. During the 2015–19 data period, there were 248 counties with a high rate of poverty (equal to or greater than 20 percent) for the veteran population. The adult non-veteran population had high poverty rates in less than half of those counties (119). Of the 129 counties in which only veterans had high poverty, there were 15 counties with extreme high poverty rates (equal to or greater than 40 percent) for veterans. Across all the 248 counties in which there was high veteran poverty, nearly 90 percent (219 counties) were nonmetropolitan counties. This chart uses data found in the ERS Atlas of Rural and Small-Town America and updates statistics that appear in the ERS Economic Brief Rural Veterans at a Glance, published in November 2013.

Friday, October 14, 2022

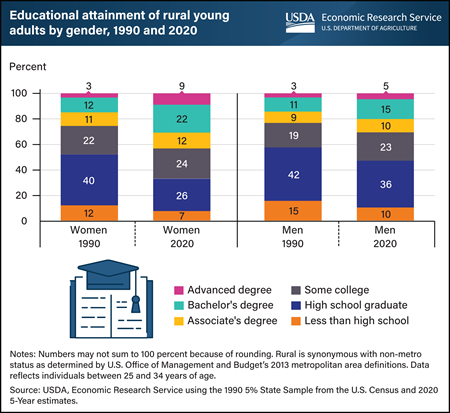

In rural areas, the level of educational attainment for women ages 25–34 continues to outpace young men. In 1990, 48 percent of rural young women had post-high school education, compared to 42 percent of rural young men. By 2020, this 6-percentage-point difference in post-high school educational attainment between the sexes increased to 14 percentage points, with 67 percent of rural, young women having post-high school education compared to 53 percent for their male counterparts. From 1990 to 2020, higher education rates for young, rural females increased almost 19 percentage points. The majority of that increase (10 percentage points) came from a rise in bachelor’s degrees, with another 6 percent coming from gains in advanced degrees, such as graduate or medical degrees. Educational attainment often has direct implications for earnings, with higher levels linked to increased wages and lower rates of unemployment, as discussed in Rural Education at a Glance, 2017 Edition. This is even more relevant for rural areas, where median earnings do not keep pace with urban area earnings. This chart updates information found in Rural Education at a Glance, 2017 Edition.

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

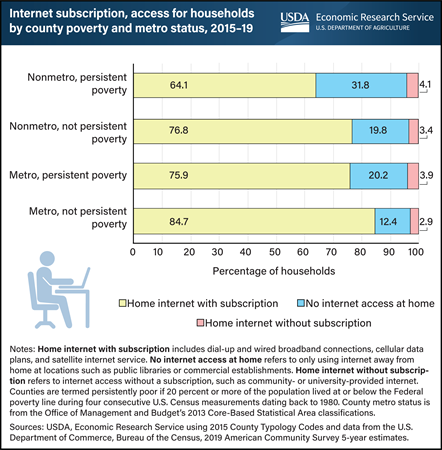

Households in rural (nonmetropolitan) persistently poor counties were the least likely to have home internet in 2015-19, with more than 3 in 10 households lacking internet access at home. In comparison, only 2 in 10 households in rural counties that were not persistently poor had no internet access at home. A similar pattern was observed in urban (metropolitan) areas, with 2 in 10 households in persistently poor counties lacking home internet access. Only a little more than 1 in 10 households in urban counties that were not persistently poor had no internet access at home. These data illustrate two major trends. First, rural households were less likely to have internet subscriptions at home than urban households. Second, in persistently poor counties, whether rural or urban, a higher share of households lacks internet adoption than in counties that are not persistently poor. For households with internet access at home, service was mainly through a subscription, which includes a range of access from dial-up to broadband to cellular data plans. These gaps in at-home internet access and subscriptions suggest that households in persistently poor counties—and more specifically, households in rural persistently poor counties—had additional barriers to internet adoption. This chart appears in the USDA, Economic Research Service report Rural America at a Glance: 2021 Edition, published in November 2021.

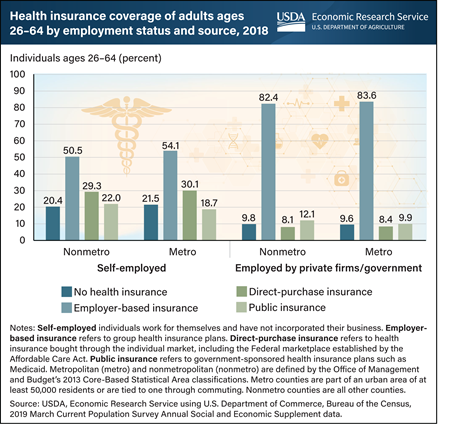

Monday, August 1, 2022

Self-employed workers were more than twice as likely to lack health insurance compared with those employed by private firms or government in 2018, regardless of whether they lived in metropolitan or nonmetropolitan counties. Self-employed working-age adults (ages 26–64) with health insurance were covered more widely across sources. Like those employed by private firms and government, they were insured through employer-based group health insurance plans more than any other source. (Many of these individuals could be receiving coverage through another household member’s employer-based plan.) Even so, a much smaller share of self-employed workers was covered by employer-based plans than those employed by private firms or government (50.5 percent versus 82.4 percent, respectively, in nonmetro counties). Instead, self-employed working-age adults were insured through direct-purchase health insurance plans at more than three times the rate of those employed by private firms or government. Similarly, public health insurance (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare) rates for self-employed working-age adults were nearly twice that of those employed by private firms or government. A version of this chart appears in the ERS publication Health Care Access Among Self-Employed Workers in Nonmetropolitan Counties published May 2022.

_450px.png?v=6054.6)

Wednesday, July 27, 2022

As the effects of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic deepened in 2020, a greater share of employed people reported lacking health insurance coverage, regardless of residential location or whether they were self-employed. Self-employed workers were already more often uninsured than those employed by private industry or government, and the gap persisted through the end of 2020. Self-employed workers started the pandemic with uninsured rates of between 24 percent and 28 percent, and these rates remained relatively stable through July 21, 2020. Thereafter, the percentage of uninsured individuals increased, and between August 19 and December 21, 2020, around 33 to 34 percent of self-employed workers were uninsured. The rates of uninsured individuals among other workers followed the same trend, with rates of 15 to 16 percent at the beginning of the pandemic increasing to around 27 percent by the end of 2020. The increases correspond both to a decrease in health insurance coverage through employer-based plans as job losses grew and to slight declines in coverage through direct-purchase plans among the self-employed. This chart appears in the ERS publication report Health Care Access Among Self-Employed Workers in Nonmetropolitan Counties, published May 2022.

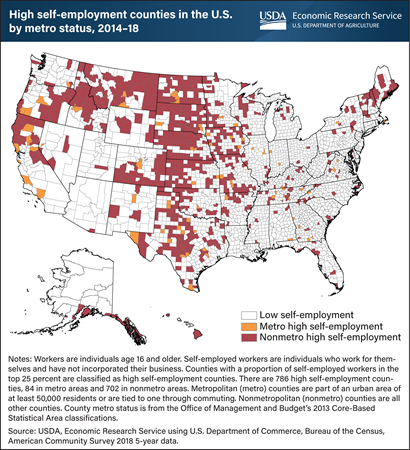

Counties with high levels of self-employed workers dominate the Great Plains and upper Mountain West

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

Self-employed workers are individuals who work for themselves and have not incorporated their businesses. A higher proportion of nonmetropolitan workers are self-employed than metropolitan workers, according to a recent study by the USDA, Economic Research Service. ERS researchers used workforce data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census’ 2014–18 American Community Survey (ACS) to classify counties by the percentage of self-employed workers. Counties with a share of self-employed workers in the top 25 percent were considered to have a high level of self-employment. In these counties, 9.1 percent to 36.7 percent of workers were self-employed. High self-employment counties were primarily nonmetropolitan (702 counties versus 84 metropolitan counties). They were largely clustered throughout the Great Plains and upper Mountain West. This figure appears in the ERS publication Health Care Access Among Self-Employed Workers in Nonmetropolitan Counties, published May 2022.

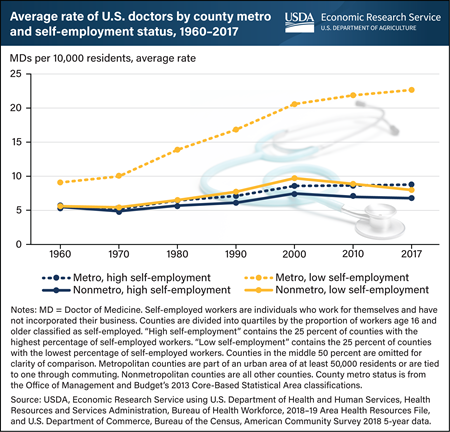

Thursday, July 7, 2022

To understand how the availability of health care for self-employed workers in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas has changed over time, researchers at USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) examined the average rate of doctors with medical degrees (not with osteopathic degrees) per 10,000 people. In this chart, they focused on differences between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties with high and low rates of self-employment. The researchers found that between 1960 and 2017, doctors have been far more available in metropolitan counties with low self-employment rates than in other counties. They also found that doctors have been the least available in nonmetropolitan counties with high self-employment rates. The largest gap in doctor availability existed between these two groups: in 2017, there was an average of 23 doctors per 10,000 residents in low self-employment metropolitan counties versus 7 doctors in high self-employment nonmetropolitan counties. However, the average rates of doctors and trends in those rates have changed over time. Between 1970 and 2000, the average rate of doctors increased in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties. But since 2000, the average rate of doctors started to decrease in nonmetropolitan counties. By 2017, the average rate of doctors in low self-employment nonmetropolitan counties fell below the rate in high self-employment metropolitan counties. Thus, people living in nonmetropolitan counties, particularly those with a higher proportion of self-employed workers, generally had less access to doctors. A version of this chart appears in the ERS publication Health Care Access Among Self-Employed Workers in Nonmetropolitan Counties, published May 2022.

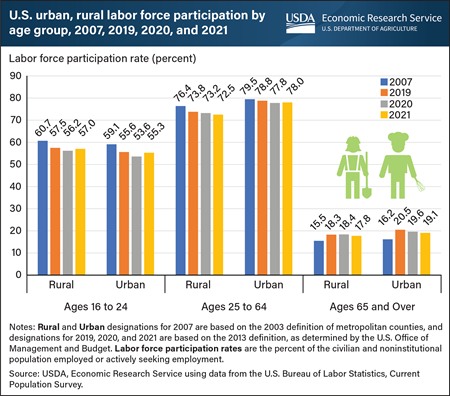

Tuesday, May 10, 2022

From 2007 to 2019, labor force participation rates (the percentage of the population that is working or actively looking for work) decreased 2.6 percentage points for people aged 25 to 64 in the rural United States and 0.7 percentage point for the same age group in urban areas. The larger decrease in rural participation reflects a slower recovery in those areas after the Great Recession, which lasted from December 2007 to June 2009. Labor force participation rates for people aged 25 to 64 decreased again from 2019 to 2020 due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic but decreased less in rural counties than in urban counties (rural 0.6 percentage point vs. urban 1 percentage point). Rates declined the most from 2019 to 2020 for people aged 16 to 24 and fell the most in that age group in urban counties. In 2021, labor force participation rates for each age group remained below pre-pandemic (2019) levels in rural and urban counties and even decreased below 2020 levels for people aged 25 to 64 in rural areas and for people 65 and over in urban and rural areas. In 2021, the labor force participation rate for people aged 16 to 24 in rural counties rebounded compared with 2020. This chart was drawn from the Rural Employment and Unemployment data page, updated March 29, 2022.

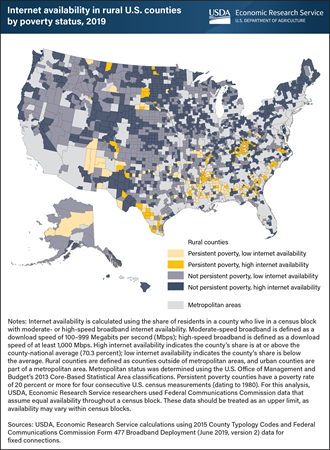

Friday, January 14, 2022

Access to fast internet speeds has been crucial throughout the Nation with the increased online presence of school, work, and shopping due to the (Coronavirus) COVID-19 pandemic. In June 2019, the moderate- or high-speed broadband internet needed for high-quality video calls was available in the census blocks of more than 90 percent of U.S. residents. In rural counties, however, only 72 percent residents had access to those internet speeds. Only 63 percent of rural residents in counties with persistent poverty had moderate or high-speed broadband available in their census blocks. Counties are considered persistently poor if they have a poverty rate of 20 percent or more for four consecutive U.S. Census measurements dating back to 1980. Among persistently poor rural counties, high availability of moderate or high-speed internet was clustered in and around eastern Kentucky and southern Texas. Rural persistently poor counties in the Deep South and Southwest had low internet availability, as did rural counties in the lower Great Plains and western Mountain States that were not persistently poor. Rural counties without persistent poverty that had high internet availability were scattered throughout the eastern half of the United States and clustered in the upper Great Plains and eastern Mountain States. This map was first published in the USDA, Economic Research Service report Rural America at a Glance: 2021 Edition.

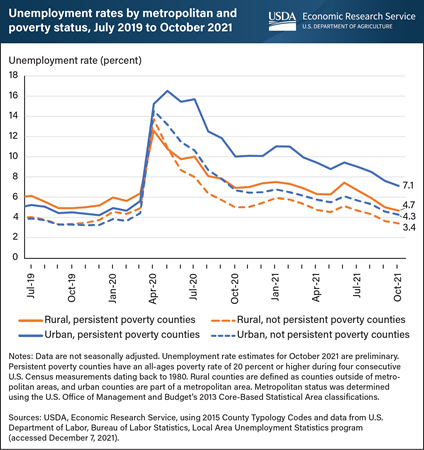

Friday, January 7, 2022

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic affected unemployment rates differently in rural and urban counties. In January 2020, just before the pandemic, the unemployment rates in rural counties, both persistently poor and not, were higher than in urban counties. In addition, the unemployment rates in persistently poor counties were higher than in counties that were not persistently poor (6 percent versus 4.6 percent, respectively, for rural counties). That changed with the pandemic-driven economic downturn. By April 2020, the unemployment rate among persistently poor rural counties had more than doubled to a peak of 12.6 percent. However, in other rural counties the unemployment rate had more than tripled, surpassing the unemployment rate in persistently poor rural counties with a peak of 13.7 percent. Similarly, in urban counties the unemployment rate more than tripled for persistently poor counties and quadrupled for other urban counties, surpassing the unemployment rates in rural counties. These changes in the unemployment rate suggest that the employment shock at the start of the pandemic was not as prominent in persistently poor counties as in counties that were not persistently poor, and that it had a larger effect on urban counties than rural counties. These changes are possibly due to differing employment dependence on industries that remained in operation, such as meatpacking, or that had less demand, such as retail and hospitality. By June 2020, the unemployment rate in not persistently poor rural counties had again fallen below the rate in persistently poor rural counties, while the rate in not persistently poor urban counties again fell below the rate in persistently poor rural counties by October 2020. As of October 2021, the unemployment rates in rural counties had returned to what they were before the pandemic, but the unemployment rate remained elevated in persistently poor urban counties. This chart updates data in the USDA, Economic Research Service report Rural America at a Glance: 2021 Edition, published in November 2021.

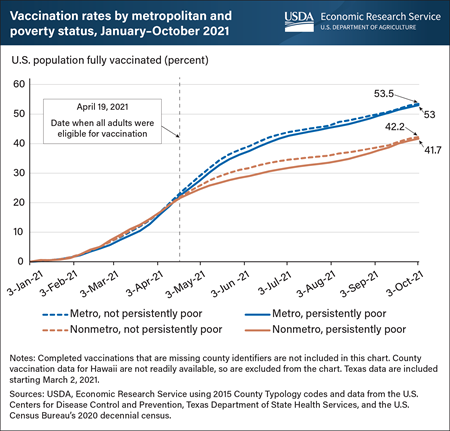

Thursday, November 18, 2021

The public rollout of Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations in the United States began in mid-December 2020. The early phases of vaccination prioritized frontline health care workers, adults age 65 and over, individuals with high-risk medical conditions, and essential workers. During this period, vaccination rates in metro (urban) and nonmetro (rural) counties increased at about the same rate, and by mid-April 2021, total vaccination rates for the Nation were slightly above 20 percent. After April 19, 2021, when all adults became eligible for vaccination, the share of fully vaccinated residents increased faster in metro counties than in nonmetro counties. In addition, the vaccination rate was consistently lower in persistently poor counties than in counties that were not persistently poor. Persistently poor counties are counties in which 20 percent or more of the population lived at or below the Federal poverty line during four consecutive U.S. census measurements dating to 1980. In July 2021, the highly infectious Delta variant began to spread. Rural persistently poor counties led the Nation in new infections through much of this surge, and the gap in vaccination rates between persistently poor and other counties started to close in mid-August. However, the rural-urban vaccination gap persisted. By early October 2021, the vaccination rate in urban counties had reached 53 percent, while the vaccination rate in rural counties was about 42 percent. This chart is included in the USDA Economic Research Service report Rural America at a Glance: 2021 Edition, published November 17, 2021.

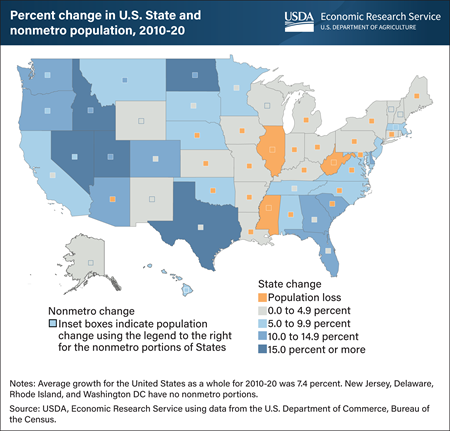

Monday, November 15, 2021

During the decade from 2010-20, 24 States lost population in nonmetropolitan, or rural areas, according to the 2020 U.S. census. Sixteen of those States lost population overall or showed slow population growth (less than 5 percent) during the period. Data from the 2020 census show the U.S. population grew 7.4 percent from 2010 to 2020, slower than the 9.7 percent growth in the previous decade. West Virginia, Mississippi, and Illinois lost population in the most recent decade, with the population declining the most in West Virginia at 3.2 percent. West Virginia also was the only State to lose population in metropolitan areas as well as in nonmetro areas. The highest-population growing State from 2010 to 2020 was Utah at 18.4 percent, and Idaho, Texas, North Dakota, and Nevada also showed population growth of 15 percent or more. This map uses data from the USDA, Economic Research Service’s State Fact Sheets data product, updated in November 2021.

Monday, August 23, 2021

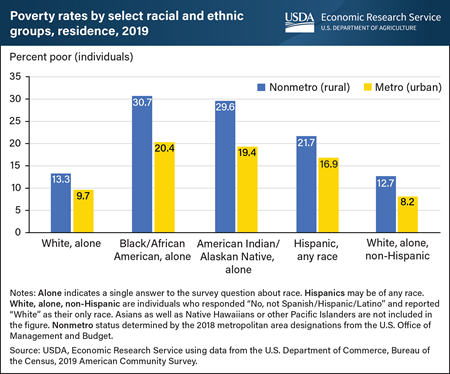

Across all races and ethnicities, U.S. poverty rates in 2019 were higher at 15.4 percent in nonmetro (rural) areas than in metro (urban) areas at 11.9 percent. Rural Black or African American residents had the highest incidence of poverty in 2019 at 30.7 percent, compared with 20.4 percent for that demographic group in urban areas. Rural American Indians or Alaska Natives had the second highest rate at 29.6 percent, compared with 19.4 percent in urban areas. The poverty rate for White residents was about half the rate for either Blacks or American Indians at 13.3 percent in rural areas and 9.7 percent in urban settings. Rural Hispanic residents of any race had the third highest poverty rate at 21.7 percent, compared with 16.9 percent in urban areas. Non-Hispanic White residents had the lowest poverty rates in both rural (12.7 percent) and urban (8.2 percent) areas in 2019. This chart appears in the Economic Research Service topic page for Rural Poverty & Well-Being, updated June 2021.

Wednesday, August 11, 2021

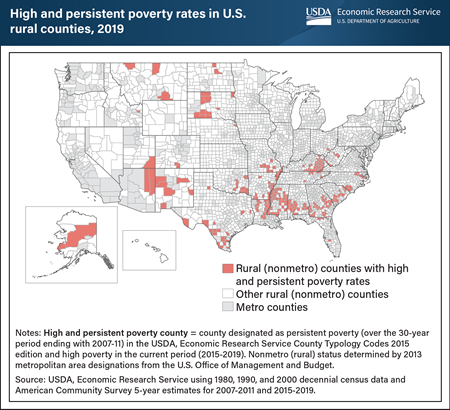

A recent USDA, Economic Research Service study of U.S. poverty identified 310 counties—10 percent of all counties—with high and persistent levels of poverty in 2019. High and persistent poverty counties had poverty rates of 20 percent or more in 1980, 1990, 2000, and on average for 2007-2011 and 2015-2019. Of those 310 counties, 86 percent, or 267 counties, were rural (nonmetro). These rural counties were concentrated in historically poor areas of the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, the Black Belt, and the southern border regions, as well as on Federal Indian reservations. More than 5 million rural residents, or about 12 percent of the U.S. rural population, lived in counties that had high and persistent poverty rates in 2019. Of those, 1.5 million individuals had incomes below the Federal poverty threshold, accounting for 20 percent of the total rural poor population. Rural residents who identify as Black or African American and American Indian or Alaska Native were particularly vulnerable. Nearly half the rural poor within these groups lived in high and persistent poverty counties in 2019. By comparison, 20 percent of rural poor Hispanics and 12 percent of rural non-Hispanic Whites lived in those counties. This chart appears in the August 2021 Amber Waves finding, Rural Poverty Has Distinct Regional and Racial Patterns.

Friday, May 28, 2021

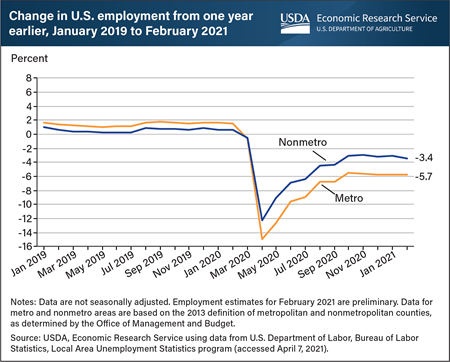

Early during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, U.S. employment fell at rates not seen since the Great Depression, with the greatest declines occurring in metro areas. Before the pandemic, employment growth in metro areas had averaged 1.4 percent per year for the 12 months prior to March 2020, more than twice the rate in nonmetro areas (0.6 percent per year). After March 2020, the situation reversed. In April 2020, metro employment was 15.0 percent below 12 months earlier, while nonmetro employment was 12.2 percent lower. Employment has since largely recovered in both metro and nonmetro areas but remained lower in February 2021 than levels 12 months earlier. The extent to which employment was still depressed in February 2021 is greater in metro areas: Metro employment was 5.7 percent lower in February 2021 than in February 2020, while nonmetro employment was 3.4 percent lower. This chart appears in the Economic Research Service topic page, The COVID-19 Pandemic and Rural America, updated May 2021.

Friday, April 2, 2021

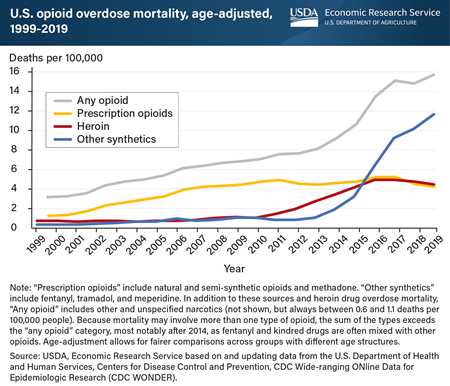

Since the late 1990s, an opioid epidemic has afflicted the U.S. population, particularly those in the prime working ages of 25-54. As a result, the National age-adjusted mortality rate from drug overdoses rose from 6.1 per 100,000 people in 1999 to 21.7 per 100,000 in 2017, then dipped to 20.7 per 100,000 in 2018 and rose back to 21.6 in 2019. Among the prime working age population, the drug overdose mortality rate was 37.8 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019. This rate was exceeded only by cancer (39.2 deaths per 100,000) in 2019 as a major cause of death in this population. ERS researchers, examining the opioid epidemic from 1999 to 2018, observed two distinct phases: a “prescription opioid phase” (1999-2011) and a succeeding “illicit opioid phase” (2011-2018), marked especially by the spread of fentanyl and its analogs. Updated data show the second phase has extended into 2019. Mortality data indicate that in the prescription opioid phase, drug overdose deaths were most prevalent in areas with high rates of physical disability, such as central Appalachia. Rural residents, middle-age men and women in their 40s and early 50s were most affected, as were Whites and American Indian/Alaskan Natives. Opioid prescriptions ceased driving the epidemic in 2011 as increased regulation and greater awareness of prescription addiction problems took hold. The illicit opioid phase that followed involved primarily heroin and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl. Fentanyl and its analogs are often used to spike other addictive drugs, including prescription opioids, creating powerful combinations that make existing drug addictions more lethal. During the study period, this second phase was concentrated in the northeastern United States, particularly in areas of employment loss. This phase most often involved urban young adult males, ages 25 to 39. All the racial/ethnic groups studied—Hispanics, Blacks, American Indian/Alaskan Natives, and Whites—were affected. This chart updates data found in the Economic Research Service report The Opioid Epidemic: A Geography in Two Phases, released April 2021.

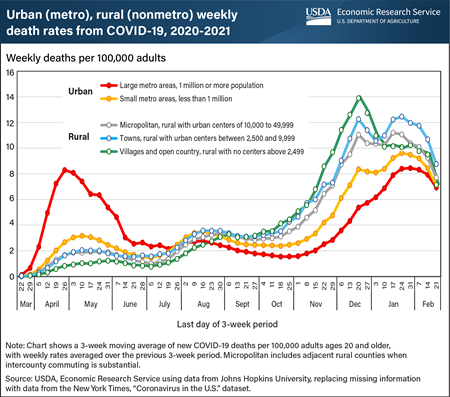

Friday, March 19, 2021

During the initial COVID-19 surge between March and June 2020, large urban areas had the highest weekly death rates from the virus in the United States. Those numbers declined as medical professionals learned more about the virus, how to treat it, and how to prevent its spread. As the virus spread from major urban areas to rural areas, the second COVID-19 surge, from July to August 2020, brought more deaths to rural areas. The peak in deaths associated with this surge was smaller because testing was more widespread, the infected population was younger and less vulnerable, and treatments were more effective. However, in early September 2020, COVID-19 death rates in rural areas surpassed those in urban areas. This trend continued into a third, still ongoing, surge that spiked in rural areas during the holiday season and again shortly thereafter. Rural areas have shown higher death rates per 100,000 adults since September in part because they had higher rates of new infections than urban areas, but that is not the whole story. Rural COVID-19 deaths per 100 new infections 2 weeks prior (to account for the lag between infection and death) were 2.2 in the first 3 weeks of February—35 percent higher than the corresponding urban mortality rate of 1.6 deaths per 100 new infections 2 weeks earlier. The rural population appears to be more vulnerable to serious infection because of the older age of its population, higher rates of underlying medical conditions, lack of health insurance, and greater distance to an intensive care hospital. As of early February, death rates have started decreasing, possibly because of more widespread vaccinations among the most vulnerable populations. This chart updates data found in the February 2021 Amber Waves data feature, “Rural Residents Appear to be More Vulnerable to Serious Infection or Death from COVID-19.”

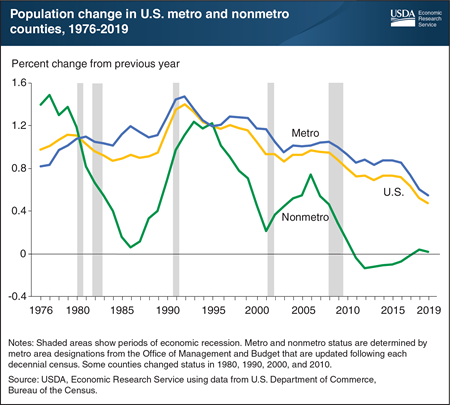

Friday, October 30, 2020

The U.S. population in nonmetro (rural) counties stood at 46.1 million in July 2019, accounting for 14 percent of U.S. residents spread across 72 percent of the Nation's land area. Nonmetro population growth has remained close to zero in recent years and was just 0.02 percent from July 2018 to July 2019, according to the latest county population estimates from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. As in previous periods of economic difficulties, such as in the mid-1980s and early 2000s, nonmetro America experienced a steep decline in population growth rates during the Great Recession. Unlike those previous periods of difficulty, the post-recession population recovery during the 2010s has been quite slow. Nonmetro population growth fell from a peak of 0.7 percent in 2006-07 to -0.14 percent in 2011-12. The nonmetro growth rate has been lower than in metropolitan (metro) counties since the mid-1990s, and the gap widened considerably in recent years. This chart appears in the July 2020 Amber Waves data feature, “Modest Improvement in Nonmetro Population Change During the Decade Masks Larger Geographic Shifts.”

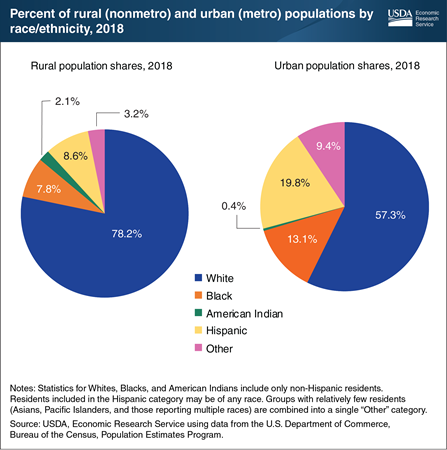

Tuesday, October 13, 2020

Rural America is less racially and ethnically diverse than the Nation’s urban areas. In 2018, Whites accounted for 78.2 percent of the rural population compared to 57.3 percent of urban areas. While Hispanics were the fastest-growing segment of the rural population, they accounted for only 8.6 percent of rural areas, but 19.8 percent of urban areas. Blacks made up 7.8 percent of the rural and 13.1 percent of the urban population. American Indians were the only minority group with a higher concentration in rural areas (2.1 percent) than urban (0.4 percent). Relatively few Asians and Pacific Islanders (included in the “Other” category) were rural residents, with these groups accounting for 0.9 and 0.05 percent of the rural population, respectively. The rest of the “Other” category reported multiple races and accounted for 2.2 percent of the rural population. This chart updates data found in the November 2018 ERS report, Rural America at a Glance, 2018 Edition.