School Food Authorities Work With State and Federal Agencies To Implement the National School Lunch Program

- by Saied Toossi and Jessica E. Todd

- 6/12/2025

Highlights

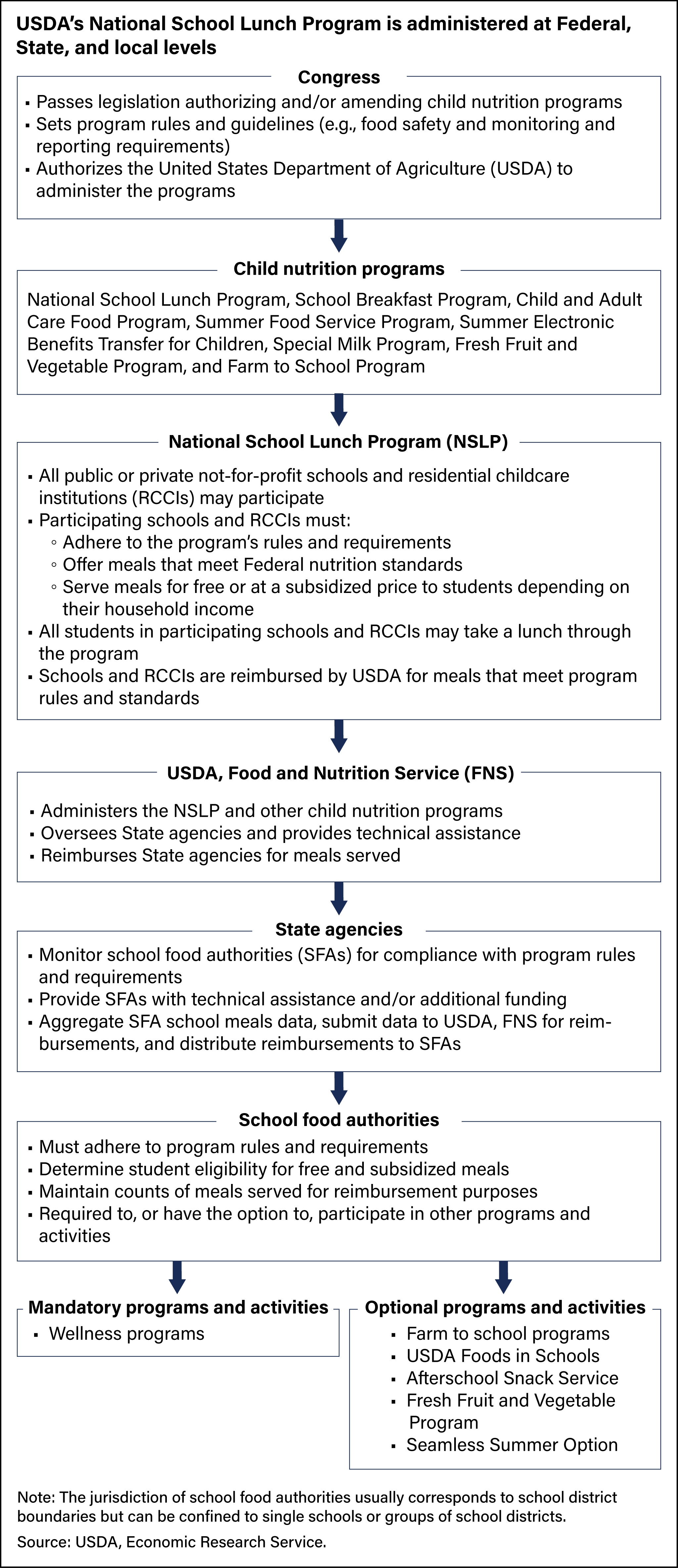

- Providing meals to children through the National School Lunch Program is a partnership between the Federal government, which sets rules and provides funding and other support; State agencies, which monitor program implementation; and school food authorities, which operate the program.

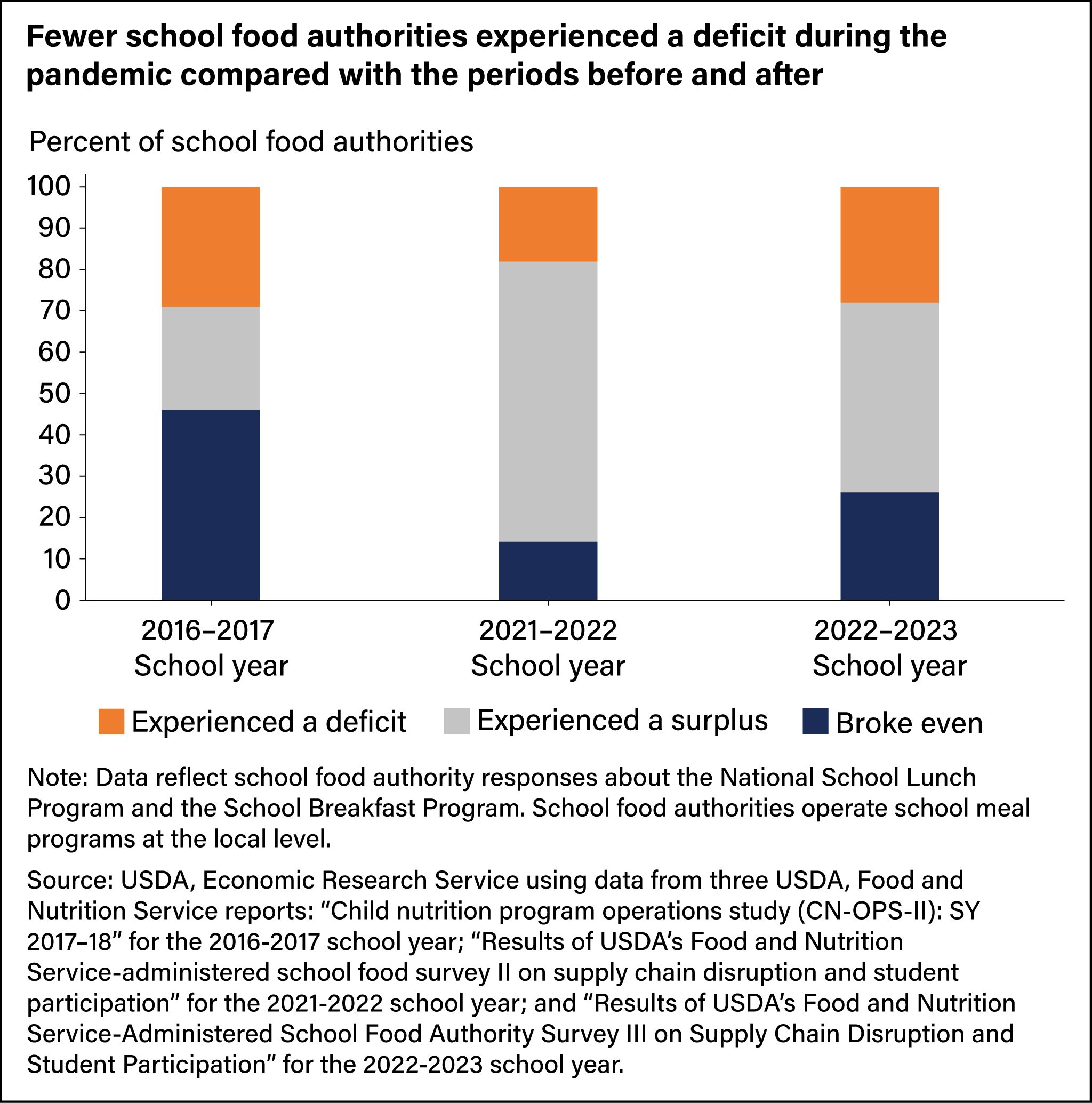

- School food authorities try to balance the costs of providing students meals that meet nutrition standards with revenues from Federal reimbursements and other sources. About 72 percent broke even or experienced a surplus at the end of the 2022–2023 school year.

- More school food authorities reported breaking even or experiencing a surplus during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic when the Federal Government had increased its support for the program compared with periods before and after.

USDA’s National School Lunch Program operates in about 100,000 public and private not-for-profit schools and serves billions of meals to tens of millions of children annually. The program makes meals available to children for free, at a reduced-price, or at full price depending on their household income and size. Schools receive reimbursements from the Federal Government for each type of meal they serve, with free meals reimbursed at the highest rate and full-price meals at the lowest rate. Research conducted by USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) staff, USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, and others shows that school meals promote better diets among participating children across income and other sociodemographic groups.

The National School Lunch Program is administered at the Federal, State, and local levels. Congress authorized the creation of the program in 1946 with the passage of the National School Lunch Act and sets the rules for implementation through legislation. For example, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 required USDA to update nutrition standards for meals served through the program to reflect goals established in the most recent edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, among other changes. Also at the Federal level, the USDA, Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) develops program regulations based on congressional legislation, reimburses States for lunches served in participating schools, coordinates program policy, provides technical assistance, sponsors research, and oversees the work of the State agencies.

State agencies administer the program through agreements with school food authorities, which are responsible for preparing and serving lunches in accordance with program rules and are usually part of the school district. State agencies are responsible for managing fiscal elements of the program, monitoring school food authorities’ adherence to the program’s rules, and providing school food authorities with technical assistance. State agencies also collect data on the number of meals served from each school food authority under their jurisdiction, report that data to FNS for reimbursement purposes, and distribute the reimbursements to the school food authorities based on their share of meals served. State agencies (and county and municipal governments) also may supplement Federal reimbursements with additional funding.

School Food Authorities Must Balance Their Costs and Revenues

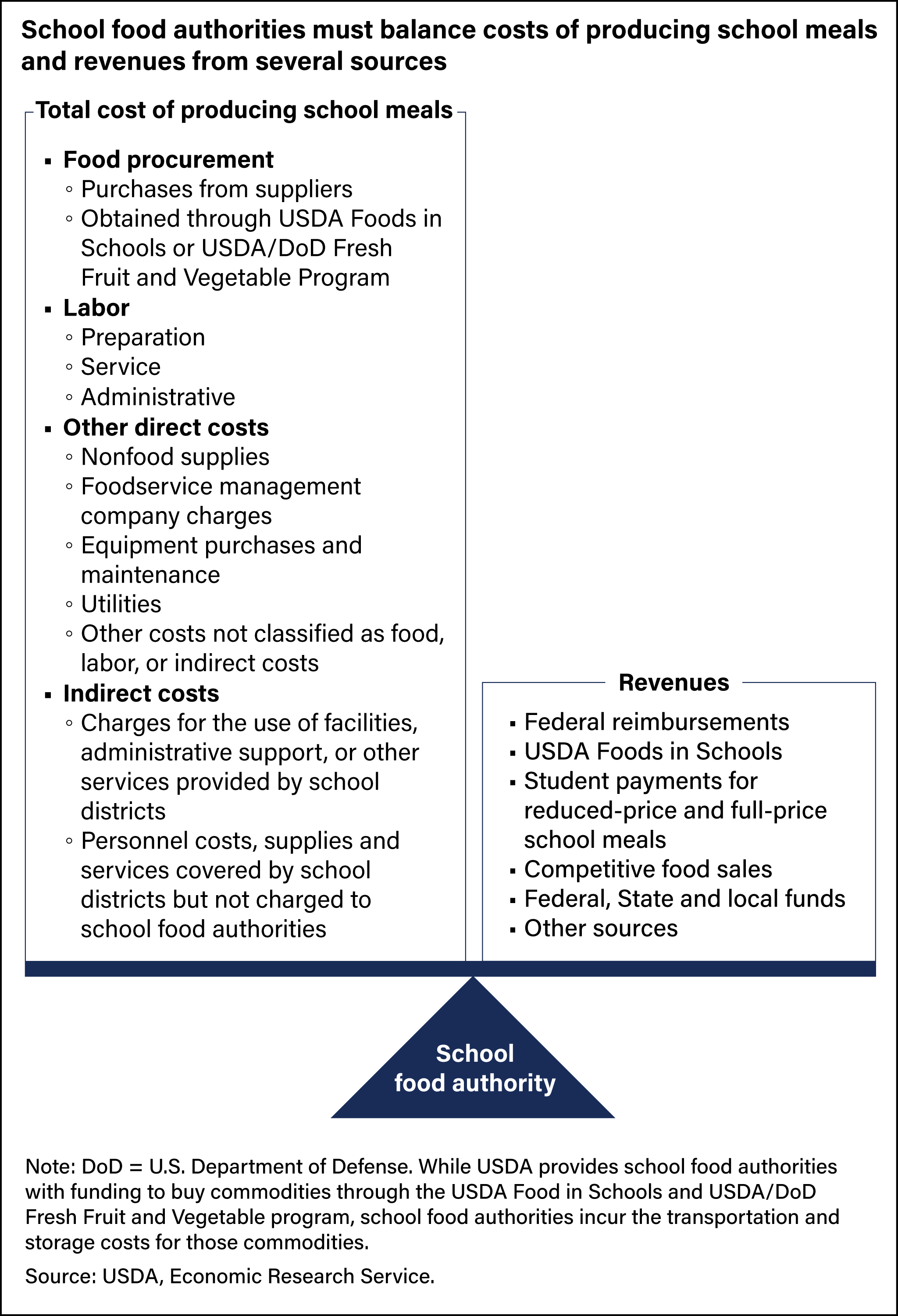

All public and private school food authorities may participate in the National School Lunch Program provided they operate their lunch programs on a nonprofit basis. As such, they aim to balance the cost of preparing and serving meals with the revenues they receive to support their lunch programs.

Several factors contribute to the full cost of preparing and serving school meals:

- labor (for preparing or serving meals, or administrative tasks);

- food (purchases from suppliers);

- other direct costs (nonfood supplies or equipment purchases and maintenance); and

- indirect costs (services provided or covered by school districts that are charged to school food authorities).

In the 2014–15 school year, labor costs accounted for 54.0 percent of total costs and procurement costs for 29.3 percent. Other direct costs accounted for 7.8 percent of total costs and indirect costs for 8.9 percent.

School food authorities generate revenues from several sources to help cover their costs:

- Federal reimbursements;

- additional Federal support through the USDA Foods in Schools Program (USDA Foods), which provides school food authorities with entitlement funds that can be used to buy foods for school meal programs;

- student payments for reduced-price and full-price lunches;

- competitive sales of foods sold in schools, such as through vending machines, outside the National School Lunch Program, or other federally supported school meals;

- other Federal, State, county, and municipal funds, such as supplemental funding provided by State governments; and

- other sources such as interest earned on deposits.

In the 2014–15 school year, Federal reimbursements accounted for 56.7 percent of school food authority revenues, student payments made up 20.0 percent, the sale of competitive foods accounted for 10.9 percent, and USDA Foods and State, county, and municipal funds made up 5.9 percent each. Other miscellaneous sources of revenues accounted for less than 1 percent of total revenues.

Most School Food Authorities Can Cover Their Costs, But Some Cannot

FNS survey data from the 2016–2017, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023 school years show most school food authorities can cover their costs. In the 2016–17 school year, several years before the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, 71 percent of school food authorities surveyed reported they could cover their costs or experienced a surplus. This share rose to 82 percent in the 2021–22 school year, during the pandemic. This increase was in part because of additional Federal support for the National School Lunch Program during the pandemic, including higher reimbursements for meals served and administrative flexibilities for implementing the program. However, as this additional support expired with the end of the pandemic and costs rose with higher inflation, the share of school food authorities that reported they broke even or experienced a surplus declined. At the end of the 2022–2023 school year, 72 percent of school food authorities reported breaking even or experiencing a surplus. That means 28 percent reported their revenues were insufficient to cover their costs at the end of 2022–2023 school year. This share was 29 percent in the 2016–17 school year and 18 percent in the 2021–22 school year.

School Food Authorities Face Challenges

A primary challenge for school food authorities is providing nutritious meals that encourage student participation in the National School Lunch Program while staying within their budgets. The rising costs of procuring food products and other supplies, recruiting and retaining the staff necessary to operate school meal programs, the purchase and installation of new equipment, and necessary cafeteria or kitchen renovations can make it difficult for some to break even while providing appealing, nutritious meals. In a November 2022 survey of school meal directors, 99.8 percent cited increasing costs as the top challenge they faced, and about the same share expressed concern that Federal reimbursement rates were inadequate to cover the cost of producing school meals.

One way that some school food authorities have potentially mitigated some of these challenges is by serving meals for free to all students, regardless of their household income, through the Community Eligibility Provision of the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act. Under the provision, schools, groups of schools, or school districts in which at least 25 percent of students are categorically eligible to receive meals at no charge to the student based on their participation in select means-tested programs (such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) receive Federal reimbursements based on a formula. The schools or school districts do not collect and process applications from families. Studies by FNS, ERS researchers, and others show that eliminating prices for school meals boosts participation in the National School Lunch Program. Higher participation increases the number of meals eligible for Federal reimbursements and may reduce the cost of preparing and serving meals through economies of scale, which, when combined with savings from not collecting and processing applications, may help school food authorities address budgetary constraints.

The number of schools providing meals at no charge to all students has increased since the Community Eligibility Provision became available nationwide in the 2014–15 school year. The number of students enrolled in a Community Eligibility Provision school rose from 6.7 million in 2014 to 16.2 million in 2021.

Beginning in 2022, as additional pandemic-related Federal support for school food authorities began to expire, several State governments opted to supplement Federal funding for school meal programs to allow all schools in their jurisdiction to serve meals at no charge to all students, regardless of the schools’ eligibility for the Community Eligibility Provision. As of November 2024, these States were California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Michigan, New Mexico, and Vermont.

This article is drawn from:

- Toossi, S., Todd, J.E., Guthrie, J. & Ollinger, M. (2024). The National School Lunch Program: Background, Trends, and Issues, 2024 Edition. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-279.

- School food authority Survey III on supply chain disruption and student participation. (2025). USDA, Food and Nutrition Service.

You may also like:

- Toossi, S. (2024, June 13). State Universal Free School Meal Policies Reduced Food Insufficiency Among Children in the 2022–2023 School Year. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Toossi, S. (2023, September 20). One-Third of Households With Children Paying for School Meals Reported That Doing So Contributed to Financial Hardship. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Ollinger, M. & Guthrie, J. (2019, April 1). Volume of Purchases and Regional Location Have Strong Effects on Food Costs for School Meals. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Ralston, K. & Guthrie, J. (2018, September 4). High-Poverty Schools Are More Likely To Adopt the Community Eligibility Provision of the USDA School Meal Programs. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Guthrie, J. & Ollinger, M. (2015, December 7). Schools Vary—And That Means Meal Costs Vary Too. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Ralston, K. & Newman, C. (2015, October 5). A Look at What’s Driving Lower Purchases of School Lunches. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Ollinger, M. & Guthrie, J. (2022). Trends in USDA Foods Ordered for Child Nutrition Programs Before and After Updated Nutrition Standards. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-239.

- Smith, T.A., Lin, B.H. & Guthrie, J. (2024). School meal nutrition standards reduce disparities across income and race/ethnicity. . American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 67(2), 249–257.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2024.03.012.

- School nutrition and meal cost study. (2024). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service.