Data Linkages Shed Light on Older USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants’ Health

- by Leslie Hodges

- 12/29/2021

Older adults made up 14 percent of the USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) total caseload in 2018. This number is expected to increase as the share of the U.S. population over the age of 60 likely doubles in the next 20 years. The health of older SNAP participants is a topic of growing interest because of high rates of chronic disease among older adults in the United States. More than 87 percent of adults age 65 years or older have at least one chronic condition and nearly two-thirds have multiple chronic conditions, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A healthy diet is known to protect against risk of disease, and SNAP supports a healthy diet by helping low-income people afford healthy and nutritious foods. However, researchers face complex challenges in linking SNAP participation to health outcomes. Studying these linkages requires a detailed understanding of participants’ health and how that differs from the health of non-participants. Small sample sizes and misreporting of program participation make it difficult to use household survey data to learn about the health of older SNAP participants. SNAP is adminstered at the State level, so SNAP administrative data—official records of program participation and benefit issuance—from a given State can be used in place of survey data to address problems of survey misreporting and sample size. However, this program data does not contain health information, so by itself cannot be used to learn about the health of older SNAP participants. These factors mean that few studies are available on the health outcomes of participation in Federal food assistance programs among older adults.

A recent collaboration between researchers from the USDA, Economic Research Service and faculty from three academic institutions aimed to overcome these limitations. Using SNAP and Medicaid program administrative data from the State of Missouri, these collaborators examined the prevalence of chronic disease and patterns in disease management among SNAP participants age 60 and older from 2006 to 2014. Their findings are among the first documented rates of chronic disease among older SNAP participants using SNAP benefit payment records for individuals linked to Medicaid claims records for the same individuals.

Moreover, they give policy makers and others a more complete look at the health of the program’s older participants. SNAP supports older adults who have dietary restrictions, such as a need for low-sodium foods, as well as older adults who must take their medications with food. SNAP also has special rules for adults age 60 and older that make it easier to qualify for benefits and remain enrolled in the program. For instance, households that consist entirely of elderly (or disabled) members are not subject to work requirements. Additionally, in some States, certification periods for the elderly (or disabled) are longer, typically lasting 24 or 36 months, rather than the standard 6 or 12 months.

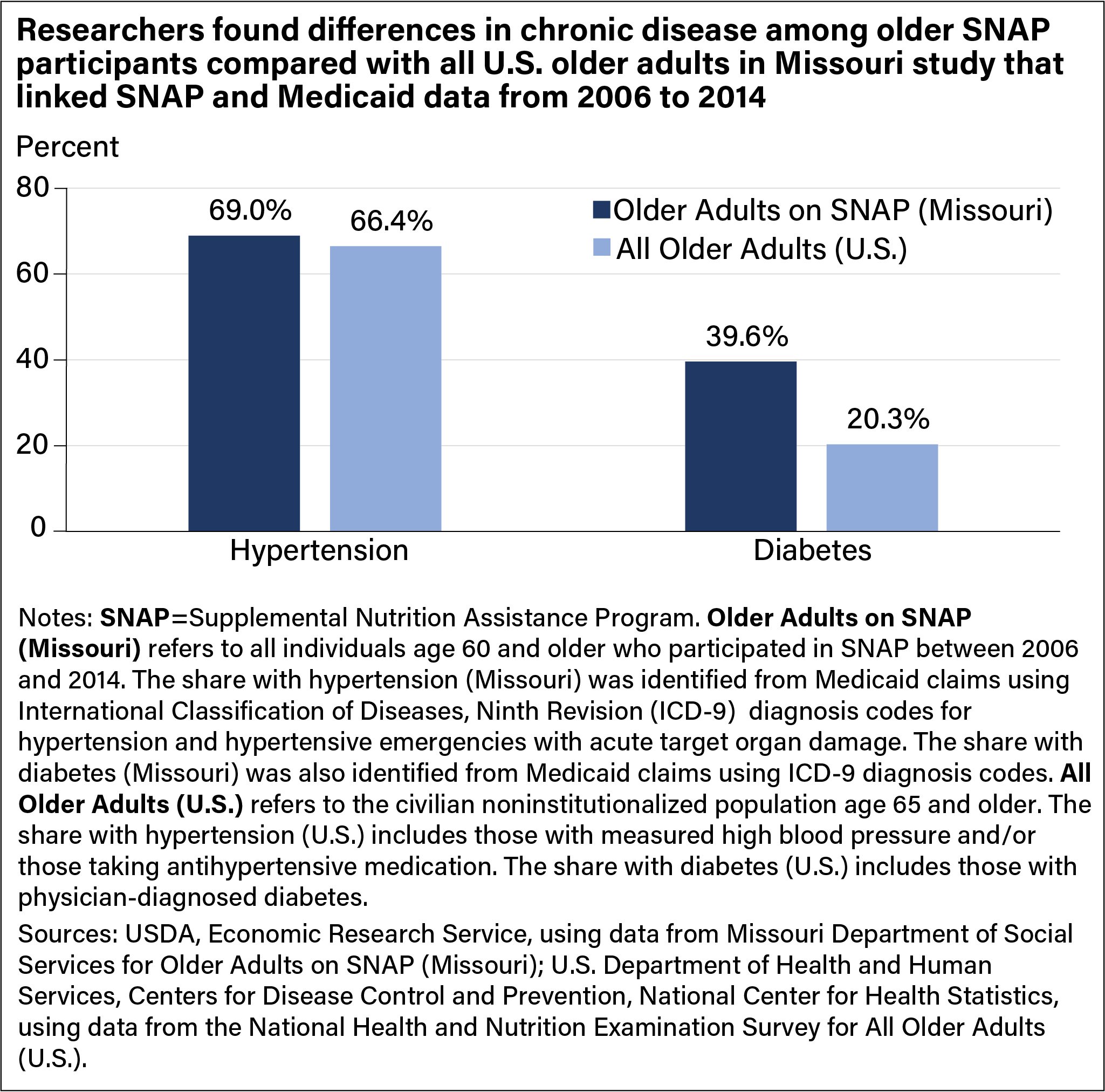

In their linkage study using Missouri data, researchers found that some SNAP participants may be at higher risk of poor health compared with the U.S. population for some health outcomes. From 2006 to 2014, the prevalence of hypertension among the State’s older adult SNAP population (age 60 and older) was similar to that of all older adults in the United States (age 65 and older)—69 percent compared with 66 percent. However, the prevalence of diabetes among Missouri’s older SNAP population, at 40 percent, was much higher than the 20 percent rate in older adults nationwide over this period. These differences are likely greater than these data indicate because the U.S. data does not include slightly younger (and presumably healthier) individuals between the ages of 60–65 that are included in the Missouri data.

This comparison of chronic disease prevalence among older SNAP participants to all older adults in the United States does not necessarily imply that SNAP participation causes poorer health. Rather, it helps establish a baseline understanding of the health of older SNAP participants for use in evaluating health impacts of future program modifications.

This article is drawn from:

- Heflin, C., Hodges, L., Ojinnaka, C. & Arteaga, I. (2021). "Hypertension, Diabetes and Medication Adherence Among the Older Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program Population". Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi: 07334648211022493.

You may also like:

- Gregory, C.A. & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2017, October 2). Adults in Households With More Severe Food Insecurity Are More Likely To Have a Chronic Disease. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Majchrowicz, A. (2018, June 4). Age Composition of USDA’s SNAP Caseload Shifts in Response to Economic Conditions, Legislation, and Demographic Trends. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Gregory, C.A. & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2017). Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working-Age Adults. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-235.