Non-converging futures and cash prices likely due to storage-rate difference

- by Economic Research Service

- 8/30/2013

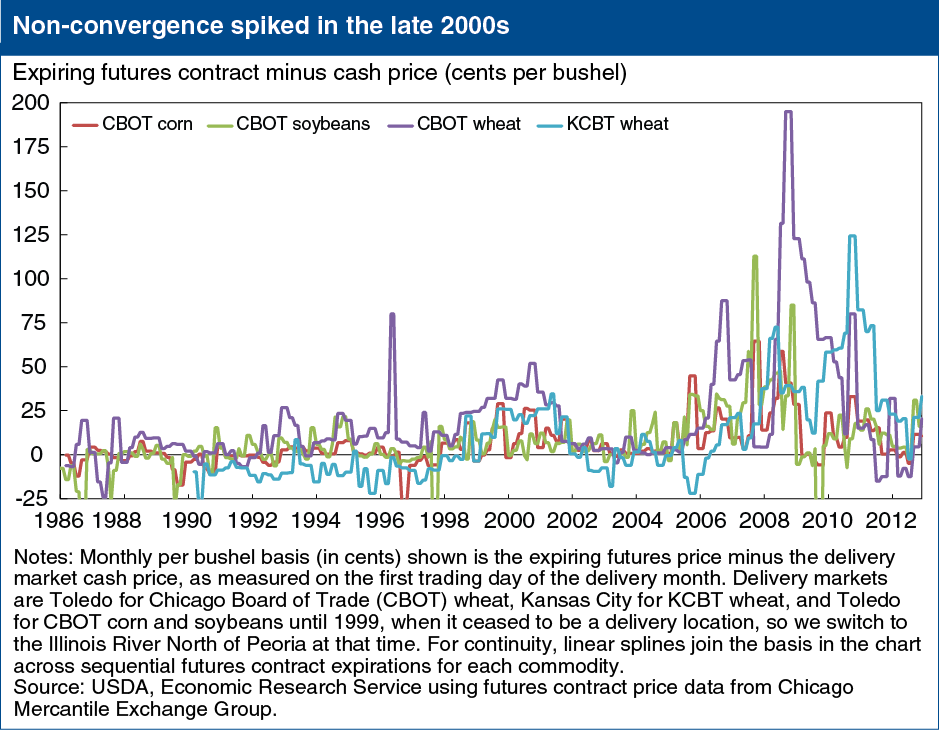

From 2005 to 2010, the prices of expiring U.S. grain futures contracts routinely exceeded the corresponding delivery market cash prices. This phenomenon, termed “non-convergence,” was particularly noteworthy in wheat markets. By appearing to simultaneously imply different prices for the same grain, non-convergence can create market uncertainty. What explains this phenomenon? When grain futures contracts expire, the seller gives the buyer a certificate that can be exchanged for a specific amount of grain, rather than transferring the actual physical commodity. Because the buyer can hold these certificates indefinitely, they provide a method to store grain, and futures exchanges charge the buyer a recurring certificate storage fee. During 2005-2010, market conditions often led the price of storing the physical commodity to exceed certificate storage fees, so expiring futures contracts became a more attractive way to store grain than holding physical grain in a warehouse. As a result, the same grain became more valuable when represented by an expiring futures contract, so the price of futures contracts rose above cash market grain prices. Addressing the divergence in storage rates is the most effective way to prevent future episodes of non-convergence. This chart is from ”Solving the Commodity Markets’ Non-Convergence Puzzle,” in ERS’s August 2013 Amber Waves magazine.