Expanded Intellectual Property Protections for Crop Seeds Increase Innovation and Market Power for Companies

- by Keith Fuglie and James M. MacDonald

- 8/28/2023

Highlights

- The U.S. crop seed sector has undergone significant structural change, spurred in part by expansions of intellectual property rights protections and innovations in biotechnology.

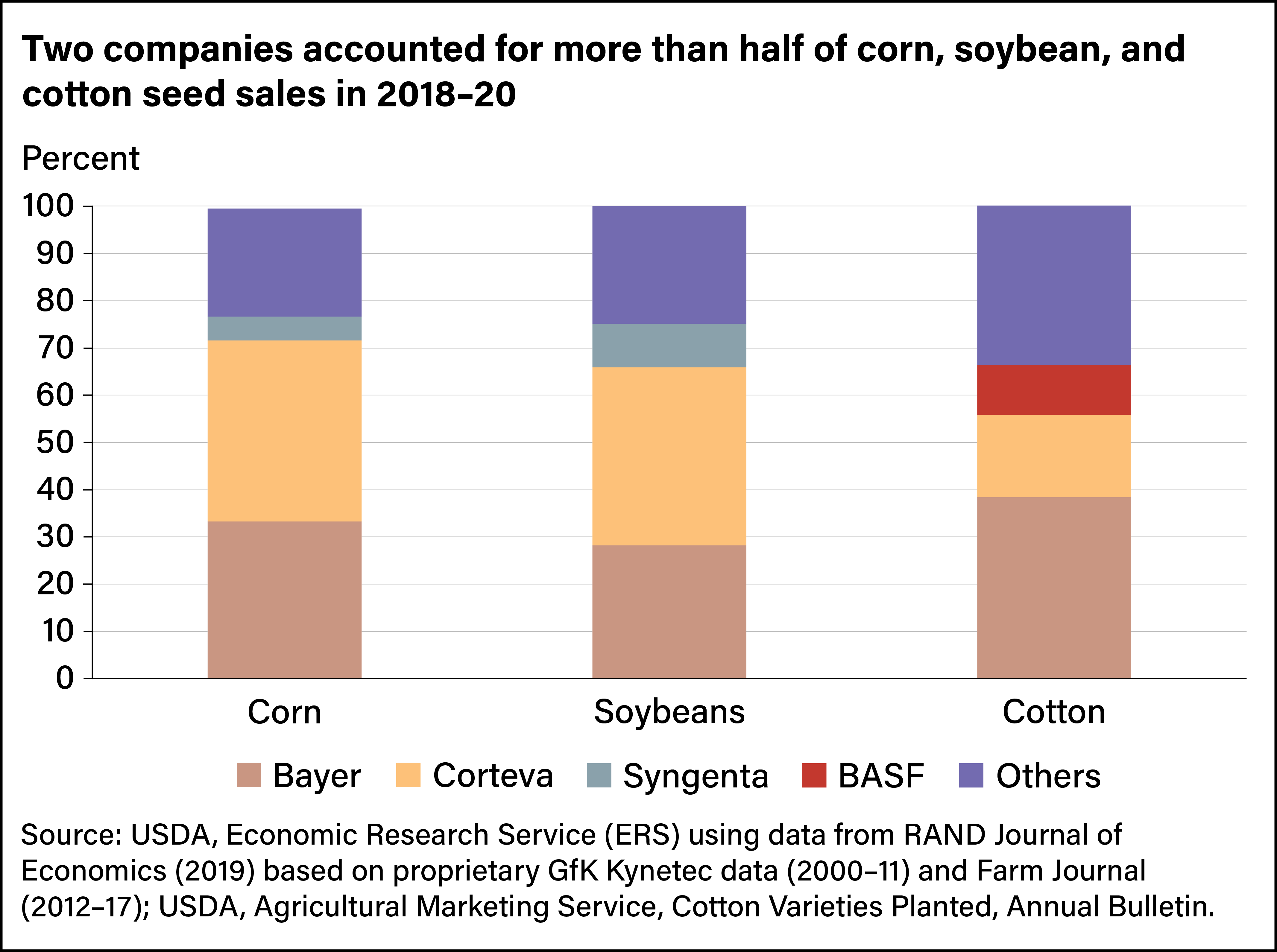

- Market concentration—measured by the share of industry sales held by the largest firms—is high in many seed markets. In 2018–20, two seed companies (Bayer and Corteva) accounted for 72 percent of planted corn acres and 66 percent of planted soybean acres in the United States.

- Stimulated by the prospect of being able to raise seed prices and earn higher revenues, seed companies increased their research and development (R&D) spending and accelerated the development of new crop varieties.

- Between 1990 and 2020, prices paid by farmers for crop seed increased an average of 170 percent, and seed prices for crops grown predominantly with genetically modified (GM) traits rose 463 percent. That compares with a 56-percent increase in commodity output prices.

In recent decades, the U.S. crop seed industry has become more concentrated, with fewer and larger firms dominating seed supply. Expanded intellectual property rights combined with structural changes in the seed industry spurred seed and biotechnology companies to increase research and development (R&D) spending that resulted in a series of innovations to crop agriculture. At the same time, seed prices have risen substantially, especially for genetically modified varieties, reflecting the value of improved seed varieties and gains in market power for top seed companies.

Expanded Intellectual Property Rights Spurred Structural Changes

Crop breeding is the science of changing plant genetics to adapt to evolving nutritional, environmental, and market needs. Before 1970, most crop breeding was done in the public sector. Private seed companies were mostly engaged in multiplying seed and distributing new varieties developed by public institutions. Farmers often saved a portion of their harvest for use as seed in subsequent seasons, periodically buying new seed to reestablish purity and quality or to adopt an improved variety. Some farmers and seed companies specialized in the production of “bin-run seed,” which is grain taken from their own crop harvest, cleaned of impurities, and perhaps treated with pesticides. They would sell the bin-run seed to other farmers for planting. But this practice left private seed companies with little financial incentive to conduct crop R&D. In selling improved seed to farmers, they also transferred the ability to reproduce the new technology. At that time, seed companies had no legal mechanism to restrict unlicensed use of their innovations.

Hybrid seed was an exception. Hybrid seed does not reproduce true-to-form, meaning it does not perform similarly across generations. To maintain yield, farmers repurchase hybrid seed each season from the seed companies that control the parental lines. The parental lines of the hybrids can be held as trade secrets—an exclusion mechanism that provides an incentive for private investment in breeding for crops where hybrid seed technology is viable. Corn was the first crop to be grown using commercial hybrid seed, and almost all corn acreage today is grown from hybrid seed, but most crops continue to be grown using self-pollinated or clonal seed rather than hybrid seed and thus reproduce true-to-form.

The 1970 Plant Variety Protection Act (PVPA) aimed to encourage seed companies to improve crop varieties beyond hybrids. Under the act, breeders could obtain a Plant Variety Protection certificate (PVPC) to protect their intellectual property rights for new varieties. Farmers were still allowed to save seed of varieties protected with the certificates, but they (and other seed companies) could no longer sell bin-run seed to other farmers except under license from the breeding company that owned the certificate. However, other seed companies and breeders could freely use protected varieties as parent material in their own breeding programs. Those protections did stimulate some private R&D, but it was uneven across crops. For example, private varieties of soybeans gradually replaced public varieties, but that was not the case for wheat and small grains.

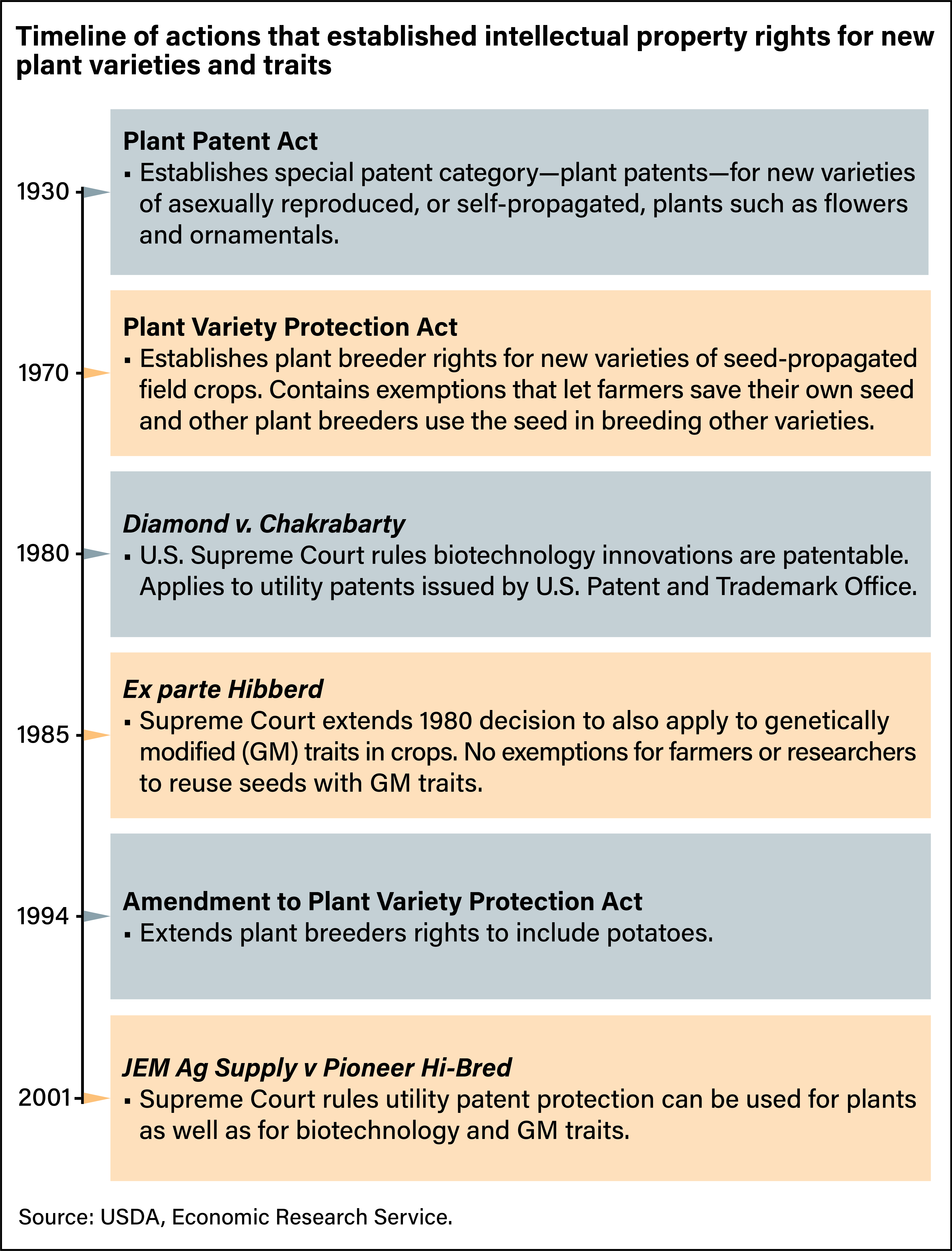

Advances in biotechnology provided a new means of improving crops by allowing genes with specific, inheritable traits to be transferred to distant crop varieties. This is the process that creates genetically modified (GM) varieties. However, development of GM varieties is expensive and risky, and without stronger intellectual property protection other than what was offered by the PVPA, there was limited incentive for the private sector to invest in that technology. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled in Diamond v. Chakrabarty that biotechnology innovations could be patented, and in 1985, a complementary decision (Ex parte Hibberd) included GM traits in crops in that ruling. Utility patents—usually the go-to patents for inventors—offer stronger intellectual property protection to seed breeders than the 1970 law because farmers cannot legally save patented crops or crop traits as seed and other companies cannot use them in breeding programs except under license from the patent owner. In 2001, in JEM Ag Supply v. Pioneer Hi-Bred, the Supreme Court extended patent protection to include plants, so new crop varieties were protected just as biotechnology and GM traits. Since that decision, companies have used patents as well as PVPCs to protect their intellectual property rights in new crop varieties (GM and non-GM), including for inbred parent lines used to produce hybrid seed.

Three types of intellectual property rights are now available for new plant varieties in the United States:

- Plant Variety Protection certificates. Created by Congress in 1970 and issued by USDA, they protect new varieties of seed crops, as well as potatoes. They include exemptions that allow breeders to use the varieties as parent material for breeding other varieties and farmers to save the varieties’ seeds for their own subsequent plantings.

- Utility patents. Issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), they can be used to protect new varieties of seed crops and plant traits. Unlike the PVPA certificates, they do not have breeder or farmer-use exemptions. Utility patents and PVPA certificates may be issued for the same crop variety.

- Plant patents. A special category of USPTO patents created in 1930, they protect asexual, or self-propagating, plants other than potatoes. They are used mainly for flowers, ornamentals, and some tree crops.

Each type of intellectual property right lasts 20 years from the date of application.

The opportunities created by expanded intellectual property rights gave private companies the incentive they needed to invest in seed-biotechnology R&D. In addition, companies with promising GM traits acquired or merged with companies that had assets in seed genetics and marketing and sales networks.

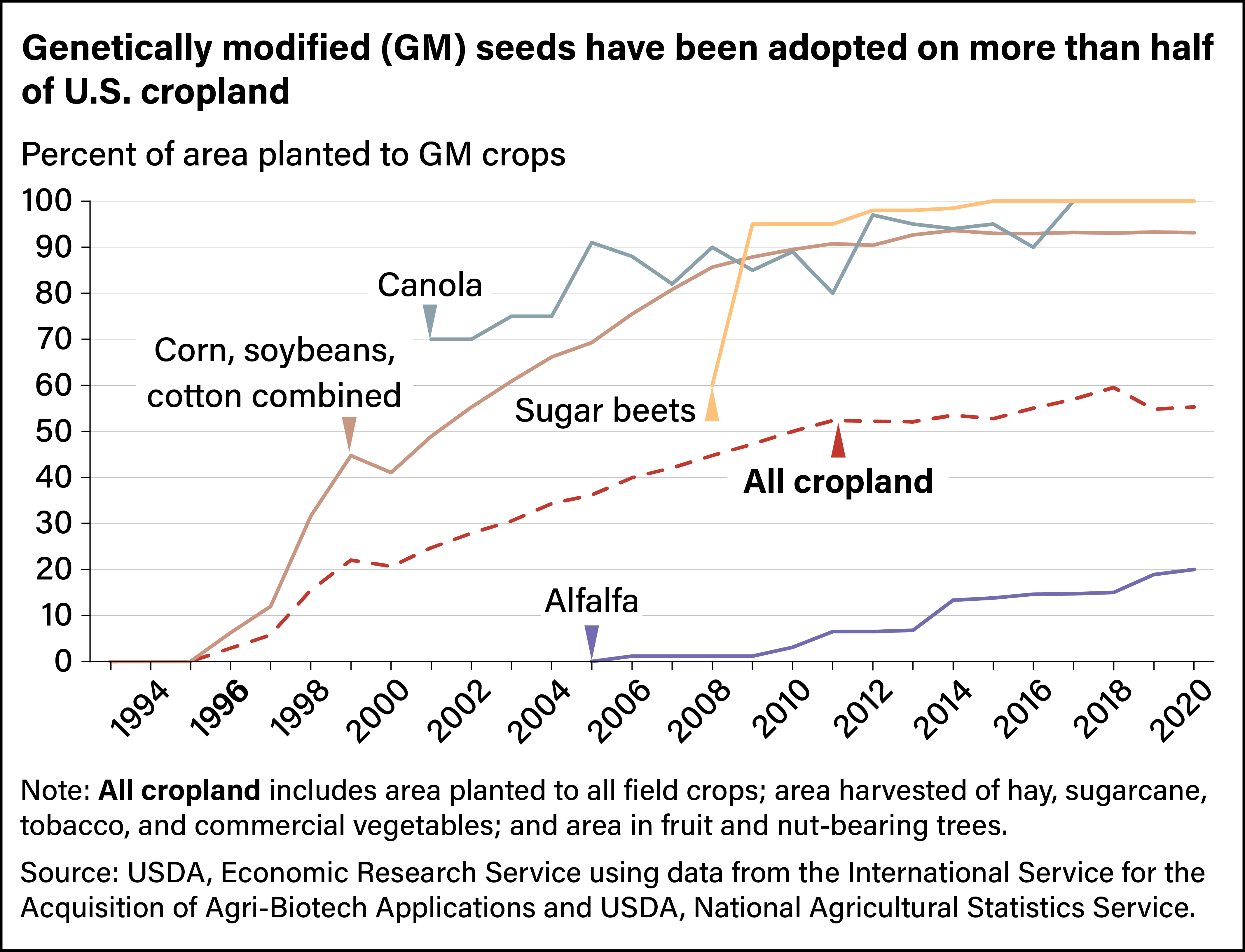

GM varieties of corn, soybeans, and cotton were introduced in the United States in 1996 and within a few years became the dominant seed choice among farmers. Later, GM varieties were widely adopted for canola and sugar beets, and their use has begun to spread in alfalfa plantings, as well as some fruits and vegetables. By 2020, about 55 percent of the total U.S. harvested cropland was grown with varieties having at least one GM trait. The most prevalent GM traits are herbicide tolerance and insect resistance.

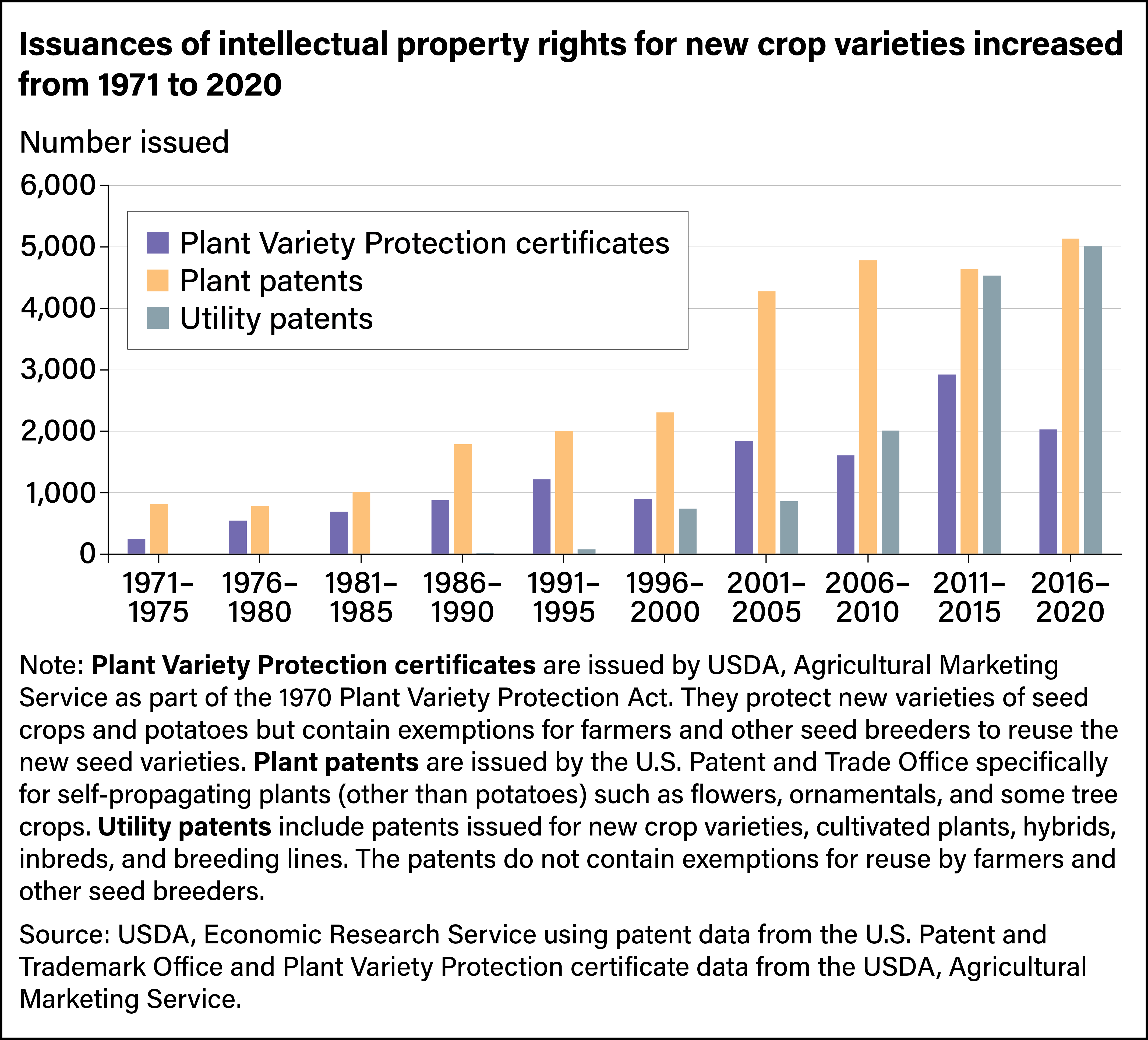

The increase in private R&D not only led to the commercialization of GM crops but also accelerated the pace of crop technology development overall. From 2016 to 2020, a total of 5,137 plant patents, 5,010 utility patents, and 2,028 PVPCs were issued for new crop varieties, more than double the rate of a decade earlier. Farmers also appear to be turning over their varieties more frequently, with the average commercial life of a newly introduced hybrid falling from around 4 to 5 years in 1997 to fewer than 3 years by 2009.

Seed Markets Involve Complex Interactions Among Industry Groups

Seed markets involve not only developers and retailers of crop varieties but also suppliers of improved parent lines, seed treatments, biotech (GM) traits, and services. A company may provide one or more product or service and sell or license them to or from other firms. Companies that sell their proprietary seed varieties to farmers often have licensed technologies from other companies to produce the seed. For example, Monsanto was an early developer of biotech traits for corn, soybeans, and cotton. It incorporated traits into its own crop varieties and licensed the traits to other seed companies to use in their own varieties. Firms with large patent portfolios have entered into cross-licensing agreements to acquire one another’s technologies. Through cross-licensing agreements, firms may be able to significantly reduce or even avoid paying royalties or licensing fees.

GM traits can be sold or licensed separately from seed and incorporated into multiple varieties and crops. Markets for those traits are thought to be highly concentrated, though available public information is limited. Licensing and cross-licensing of GM traits are common, and a single variety may have multiple GM traits licensed from multiple companies. While some of the early patents for GM traits have expired or are soon expiring, it is not clear whether generic versions of these traits will become available for commercial use.

To use a GM trait in crop production, regulatory approval must be secured and maintained by the trait developer in each country where the seed is grown. Countries also may require regulatory approval for the intended use (food or animal feed) of imported crops containing GM traits. The patent holder or licensee usually bears the cost of maintaining regulatory approvals. If the approvals lapse, those traits can no longer be used in commercial varieties or in the crops sold for commercial use in those countries.

Market concentration is likely to be high for crop seed for which GM traits are popular (such as canola, sugar beets, and alfalfa) and is probably lower in markets where conventional seed varieties dominate and where public-sector varieties and farmer-saved seed continue to be widely used (such as for wheat and other small grains, peanuts, and dry beans). The market for vegetable seeds appears to be dominated by private-sector varieties but is diverse across species. Large seed-chemical companies such as Bayer and Syngenta have significant investments in proprietary vegetable seeds, but midsized companies (including several Dutch companies) also have a significant presence in U.S. and global seed markets for specific vegetables.

As seen in the chart below, two companies—Corteva and Bayer—accounted for more than half of the retail seed market sales of corn, soybeans, and cotton in 2018–20.

Spate of Mergers Reduces “Big Six” Seed Companies to “Big Four”

In 2015, six firms dominated global markets for seeds and agricultural chemicals: BASF, Bayer, Dow Chemical, DuPont, Monsanto, and Syngenta. Sometimes referred to as the “Big Six,” these firms produced and sold pesticides (primarily herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides), seed treatments (seed coatings to protect against insects or fungi), crop seeds, and seed traits. Then ChemChina, a state-owned Chinese company, acquired Syngenta; Dow Chemical and Dupont merged and spun off their combined agricultural businesses into a firm called Corteva; and Bayer acquired Monsanto. The transactions reduced the “Big Six” to a “Big Four” and eliminated two of the three U.S. firms.

Antitrust regulatory authorities reviewed the mergers in the firms’ two biggest markets, the United States and the European Union (EU), as well as in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, and South Africa. Focusing on the economic repercussions of market power, the reviews and their resolutions concentrated on whether the mergers’ resulting reduction in competition could lead to higher production costs for farmers and reduced R&D spending and, therefore, lead to less innovation.

The United States and European Union investigations of the Dow Chemical-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto mergers focused on their likely effect on innovation, especially in several highly concentrated markets for traits, seeds, and pesticides. The antitrust agencies argued that with fewer competitors, new innovations would compete with existing products instead of diverting business from rival firms. In those cases, a firm would be less likely to invest in research to develop innovations. The U.S. and EU regulators in particular focused on several pesticide markets in the Dow-DuPont merger. In the Bayer-Monsanto merger, agencies expressed concerns with several GM seed and trait markets, five vegetable seed markets, and markets for certain seed treatments and herbicides. In each case, the merging firms were active or potential competitors and faced few or no other rivals.

Enforcement agencies approved the mergers, but with stipulations: The merged companies had to divest some businesses to other firms to maintain competitive rivalry in the markets identified as problematic. DuPont was required to sell part of its pesticide business, including R&D assets, to FMC Corp., a firm already active in agrichemicals. DuPont also sold its Brazilian corn seed business to meet the antitrust objections of the Brazilian enforcement agency. Bayer sold seed, seed trait, seed treatment, and pesticide businesses to BASF, a “Big Six” firm that had dealt primarily with pesticides but had a limited seed business.

Seed Price Increases Reflect Value of Improved Traits, New Market Power for Companies

With U.S. seed markets concentrated among fewer companies, and with expanded protections of individual property rights, seed prices have risen, especially for seed with GM varieties. Between 1990 and 2020, the average price farmers paid for seed rose 270 percent, compared with commodity price inflation of 56 percent. For crops planted predominantly with GM seed (corn, soybeans, and cotton), average seed prices were 463 percent higher in 2020 than 30 years earlier and at their peak in 2012 were 600 percent above 1990 levels. Despite their higher cost, GM crop varieties brought significant productivity gains to farmers. Yields increased, and farmers were able to cut production costs as genetic traits reduced the need for other inputs. For example, GM traits that made crops resistant to insects meant farmers could apply less insecticide.

One factor in the seed cost increase was the expanded market power of seed companies. Patents (and to a lesser extent PVPCs) offer owners of intellectual property a legal monopoly over the use of their inventions. For inventions with market value, intellectual property rights give firms the ability to set prices for the products that contain their inventions. The profits earned are a return for R&D investments and other costs to commercialize the invention. In addition, moving from a system in which privately owned inventions replace publicly financed inventions provided to users at nominal cost also affects who pays for, and who benefits from, technological change in agriculture. Inventions by private firms are financed by the price premiums they can charge users. Historically, public institutions like the USDA or land grant universities provided their inventions freely to users, but now, like their private counterparts, they may obtain patent rights and charge licensing fees for commercial use of their innovations.

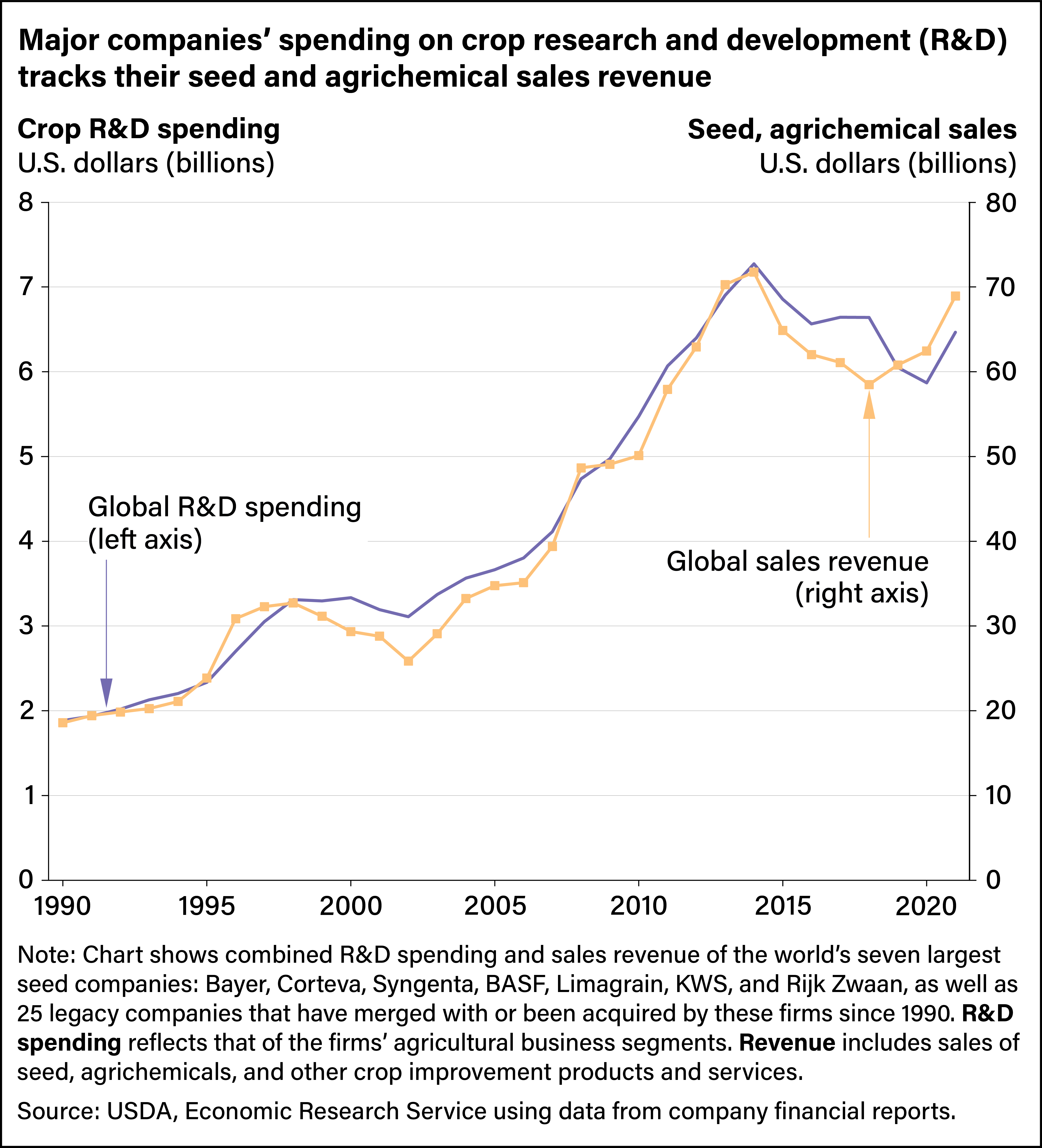

The market power provided by expanded intellectual property protection and market concentration has allowed seed companies to spend more on crop R&D, accelerate the rate of new variety introductions with higher productivity potential, and charge higher prices reflecting the value of improved seeds. Coinciding with the introduction of GM varieties, total R&D spending on crop improvement by the seven largest seed companies (including their legacy companies) increased from less than $2 billion in 1990 to more than $7 billion by 2014, closely tracking increases in company revenues from seed and agrichemical sales. These companies have invested about 10 percent of their agricultural revenues in R&D.

A firm’s ability to exercise market power also may be affected by the concentration levels in an industry. Economic theory suggests that some degree of market power leads to private R&D investment. However, too much market concentration may reduce competition and take away firms’ incentive to innovate. The cost of R&D and regulatory requirements might deter firms from entering the field, further limiting competition and new sources of innovation.

Antitrust agencies have focused more heavily on innovation concerns in the last two decades; these concerns have become an important feature in a growing number of cases across the economy and in agribusiness. However, not much empirical evidence exists on the effect of competition on research investments and innovation—and, specifically, on how many rivals are necessary to spur innovation. This issue will remain an important question for antitrust policy and economic research.

This article is drawn from:

- MacDonald, J.M., Dong, X. & Fuglie, K. (2023). Concentration and Competition in U.S. Agribusiness. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-256.

You may also like:

- MacDonald, J.M. (2019, February 15). Mergers in Seeds and Agricultural Chemicals: What Happened?. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- MacDonald, J.M. (2017, April 3). Mergers and Competition in Seed and Agricultural Chemical Markets. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Fuglie, K., Ballenger, N., Day Rubenstein, K., Klotz, C., Ollinger, M., Reilly, J., Vasavada, U. & Yee, J. (1996). Agricultural Research and Development: Public and Private Investments Under Alternative Markets and Institutions. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. AER-735.

- Fuglie, K., Heisey, P., King, J., Pray, C.E., Day Rubenstein, K., Schimmelpfennig, D., Wang, S.L. & Karmarkar-Deshmukh, R. (2011). Research Investments and Market Structure in the Food Processing, Agricultural Input, and Biofuel Industries Worldwide. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-130.

- Valuing product innovation: Genetically engineered varieties in U.S. corn and soybeans. (2019). RAND Journal of Economics. 50, 615–644.