Consumers’ Interpretation of Food Labels with Production Claims Can Influence Purchases

- by Kar Ho Lim and Elina T. Page

- 3/7/2022

Highlights

- Food labels—such as labels that describe chicken as raised without antibiotics or using organic farming methods, canned tuna as sustainable, and beef as grass-fed—can inform consumers about animal-raising claims or other attributes that are difficult for consumers to verify independently.

- Research shows that consumers use label information to distinguish product characteristics and may be willing to pay a premium for certain product features.

- Experimental evidence finds that the willingness to pay for the label “grass-fed” on beef products is more pronounced for consumers who believe that the label signals food safety, suggesting consumers may not fully understand the meaning of the label.

Food labels can help consumers select products with attributes they value that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to verify, such as whether a package of chicken at the grocery store was raised without antibiotics. To make informed product choices, however, consumers must be able to properly interpret food labels. In some cases, consumers may not fully understand a label’s meaning or a food label may conjure perceptions that lack scientific backing or are against scientific consensus. For example, consumers may assume a label about sustainable farming practices means the food is safer to eat, which may not be true. USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) researchers recently carried out three studies on food labels to better understand how different labels affect buying behavior.

A Market Transformation: Chicken Products Raised Without Antibiotics

In the United States, antibiotics are used to treat, control, and prevent animal disease. However, the use of any antibiotics may lead to antibiotic resistance, which can in turn make both human and animal diseases difficult and costly to treat. In recent years, consumers have become increasingly concerned about antibiotic resistance and the use of antibiotics in the meat and poultry industry. These concerns have given rise to a market for meat and poultry that are “raised without antibiotics (RWA).” The USDA, Food Safety and Inspection Service, which is responsible for the labeling of meat, poultry, and egg products, provides guidelines on labeling meat and poultry products as RWA. The label allows consumers concerned about the use of antibiotics in meat and poultry to purchase products free from antibiotics. Using national household scanner data, a recent ERS report analyzed the market for chicken products with the RWA label.

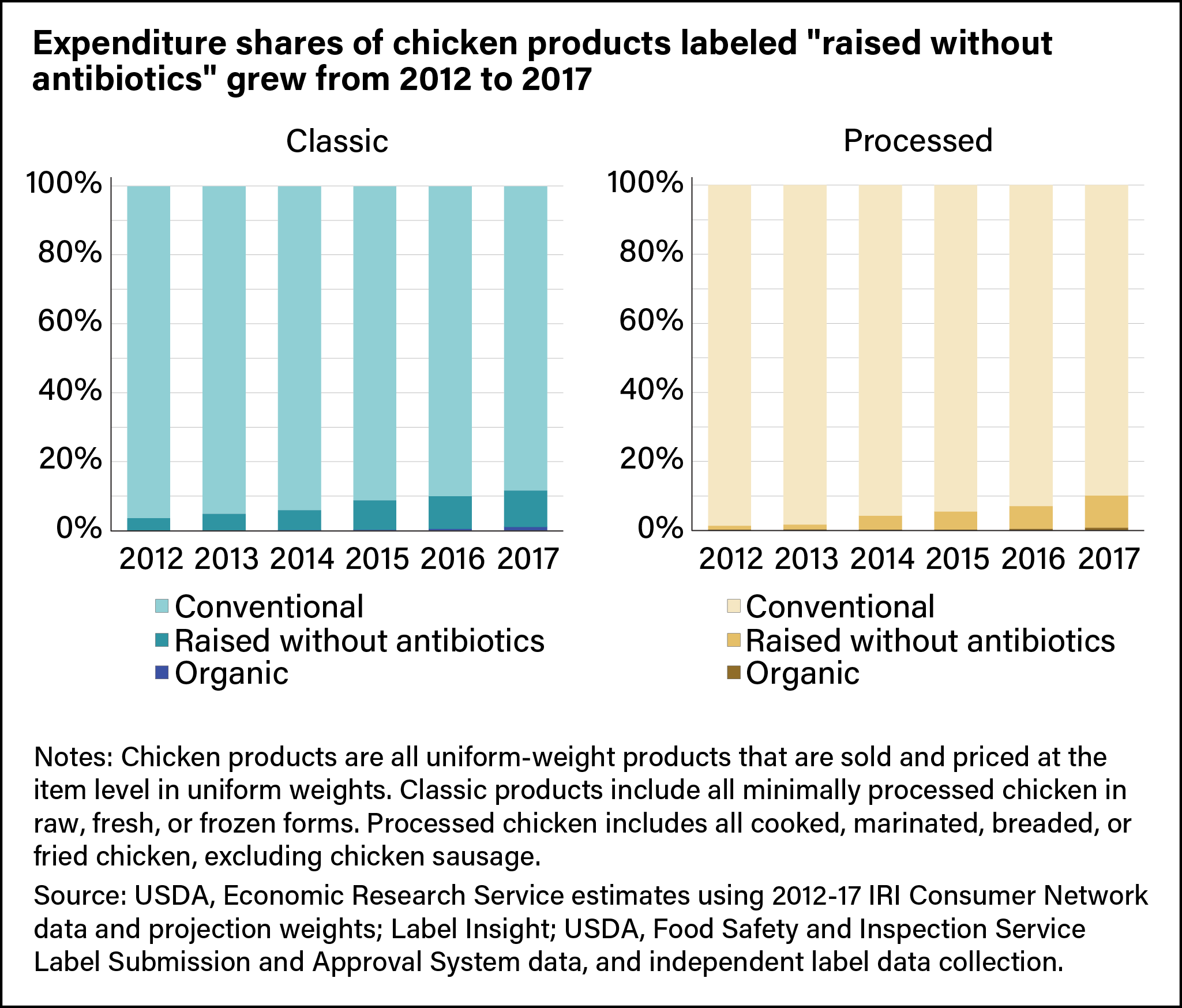

Consumer spending on RWA chicken grew considerably from 2012 to 2017. The ERS study examined two main product segments: classic, which includes all minimally processed chicken in raw, fresh, or frozen forms, and processed, which includes all cooked, marinated, breaded, or fried chicken (excluding chicken sausage). Between 2012 and 2017, the market share of classic RWA chicken products grew from 4 to 11 percent and the market share for processed RWA chicken products grew from 1 to 9 percent. For comparison, USDA-certified organic products represented only 0 to 1 percent of the market for both classic and processed chicken over the same period.

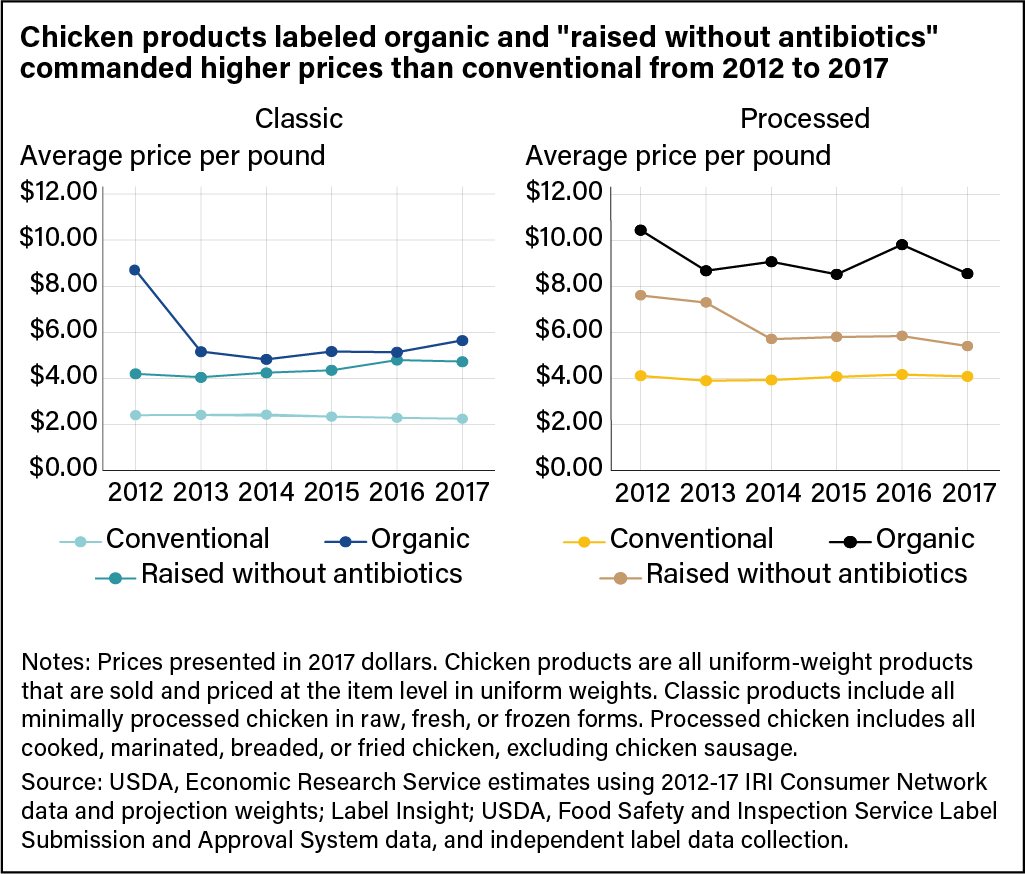

The ERS study also examined the prices of conventional, RWA, and organic chicken products from 2012 to 2017. Overall, both the classic and processed chicken markets showed a common pricing hierarchy: organic, RWA, and conventional in descending order of prices. Classic and processed RWA products were, on average, 87 percent and 55 percent more expensive, respectively, compared to similar conventional chicken products. Prices for organic chicken products were only slightly greater than RWA in the classic segment except for 2012. However, prices for organic processed chicken products were 46 percent higher than RWA processed chicken products—an additional $2.90 per pound higher, on average.

The ERS study also found that consumer concerns over the use of antibiotics and perceptions of risk were important factors in chicken purchasing decisions. More RWA and organic chicken product consumers (26 and 32 percent, respectively) reported that they were very concerned about antibiotic use in meat production compared to conventional consumers (21 percent). The inverse relationship also held true: Significantly more conventional consumers (44 percent) reported that they were not at all concerned about antibiotic use in meat production compared to RWA and organic consumers (40 and 35 percent, respectively).

Consumer Preference for Foods with Eco-labels

Another type of label that has emerged to communicate product characteristics are eco-labels, or environmental labels. These labels typically signal environmental stewardship practices in raising animals or sustainable harvesting practices. An increasing number of eco-labels are being used to market foods, such as USDA Organic, Rainforest Alliance, and Marine Stewardship Council labels. While the growth in the number of eco-labels suggests they are in demand, it is not well understood how eco-labels may interact with other food labels to affect consumer behavior.

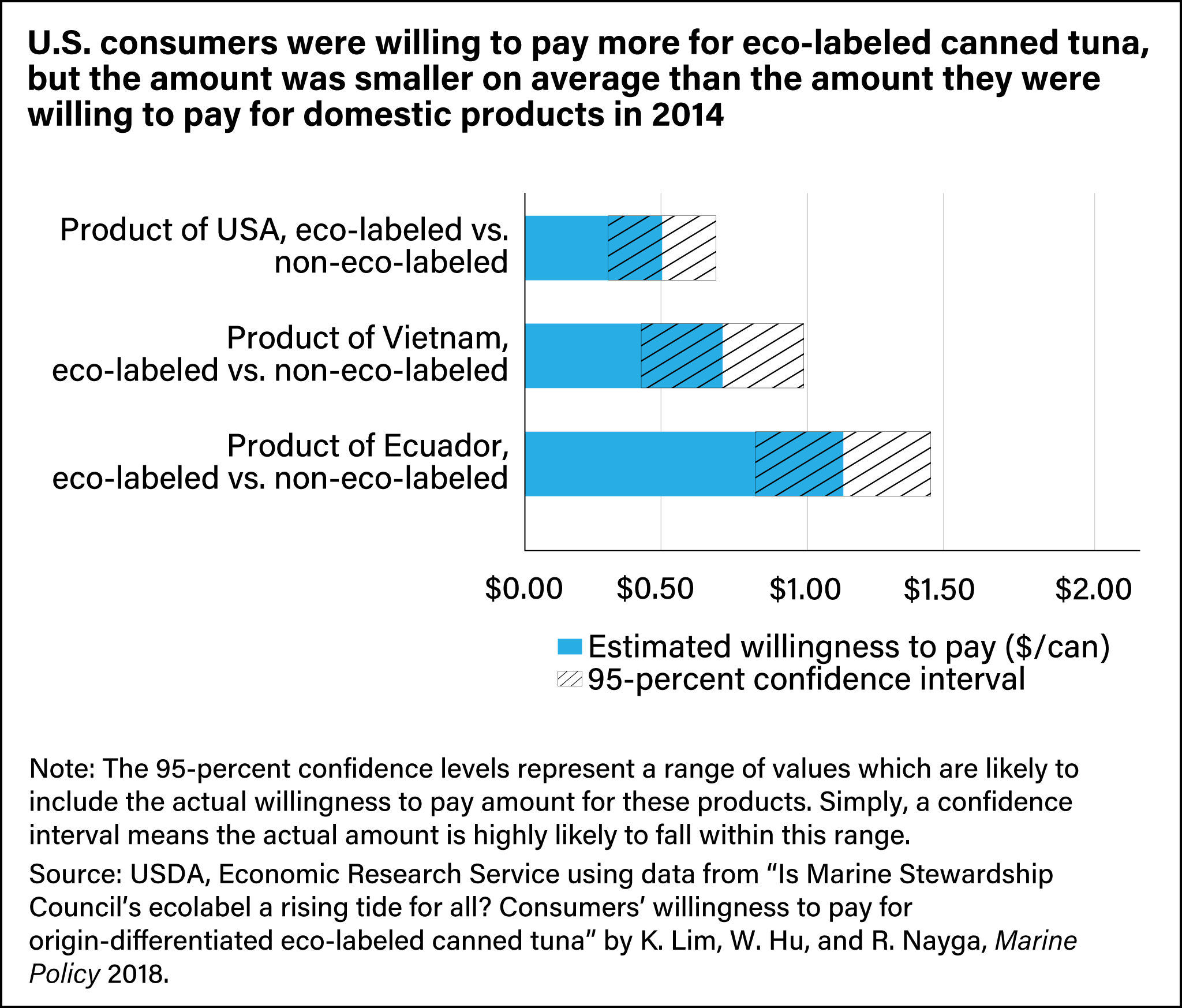

An ERS researcher and two faculty members from academic institutions examined U.S. consumers’ willingness to pay for origin-differentiated canned tuna with the Marine Stewardship Council’s sustainable seafood eco-label. They studied whether the willingness to pay for this eco-label varied depending on the country of origin of the product. This analysis was carried out with data from more than 1,000 seafood consumers that participated in a choice experiment—a survey tool that elicits the value which people place on goods or attributes.

The research found that consumers were generally willing to pay more for canned tuna with the eco-label than those without the eco-label. However, the willingness to pay varied according to the product’s country of origin. For canned tuna with the “Product of USA” label, consumers were willing to pay $0.45 more on average per can for products with the eco-label. For products of Vietnam and Ecuador respectively, the eco-label elicited additional willingness to pay $0.70 and $1.13 more on average per can.

The willingness to pay for eco-labels on canned tuna suggests that consumers are conscious about the environmental impacts of food production, such as climate change effects and natural habitat destruction. However, the differences in willingness to pay amounts for eco-labels by country of origin reveal that food labels can interact with other factors to influence consumers’ preferences.

Do Consumers Think Grass-Fed Beef Is Safer Than Conventional Beef?

Grass-fed is another production claim that is sometimes labeled on beef products. Grass-fed refers to beef derived from cattle primarily raised on a grass-fed diet. Consumers may be drawn to grass-fed beef for various reasons, such as nutritional values, taste, animal welfare, and environmental concerns. In comparison, organic beef may or may not be grass-fed, as organic grain may be used for feed. Organic beef also differs from grass-fed beef in other aspects. For example, organic cannot receive antibiotic or hormone treatments.

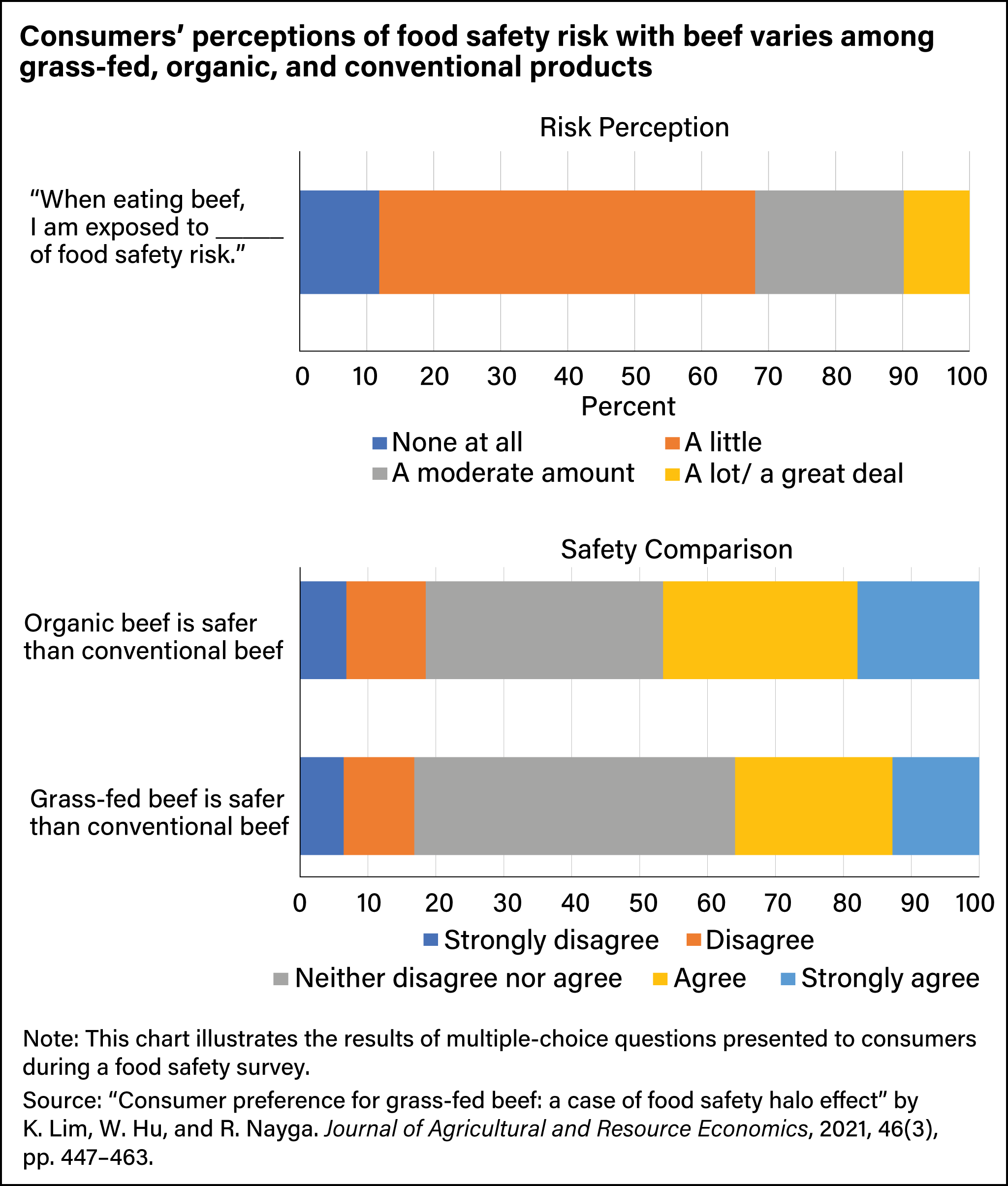

An ERS researcher and two faculty members from academic institutions used a choice experiment to examine if consumers’ willingness to pay for grass-fed beef is influenced by perceptions of food safety. The study asked 1,010 U.S. consumers about their perception of the food safety risk associated with eating beef. Food safety risk was defined for participants as the risk of food contamination from bacteria, viruses, and toxins that cause foodborne illnesses. Respondents were also asked if they agree that grass-fed beef is safer (i.e., lower in food safety risk) than conventional grain-fed beef.

Overall, most respondents perceived low food safety risk from eating beef, as only about one-third reported “a moderate amount” to “a great deal” of risk. Nearly 40 percent believed grass-fed is safer, compared to conventional beef; in contrast, nearly 50 percent believed organic beef is safer. On average, consumers were willing to pay around $1 per pound more for grass-fed and organic beef compared to conventional grain-fed beef.

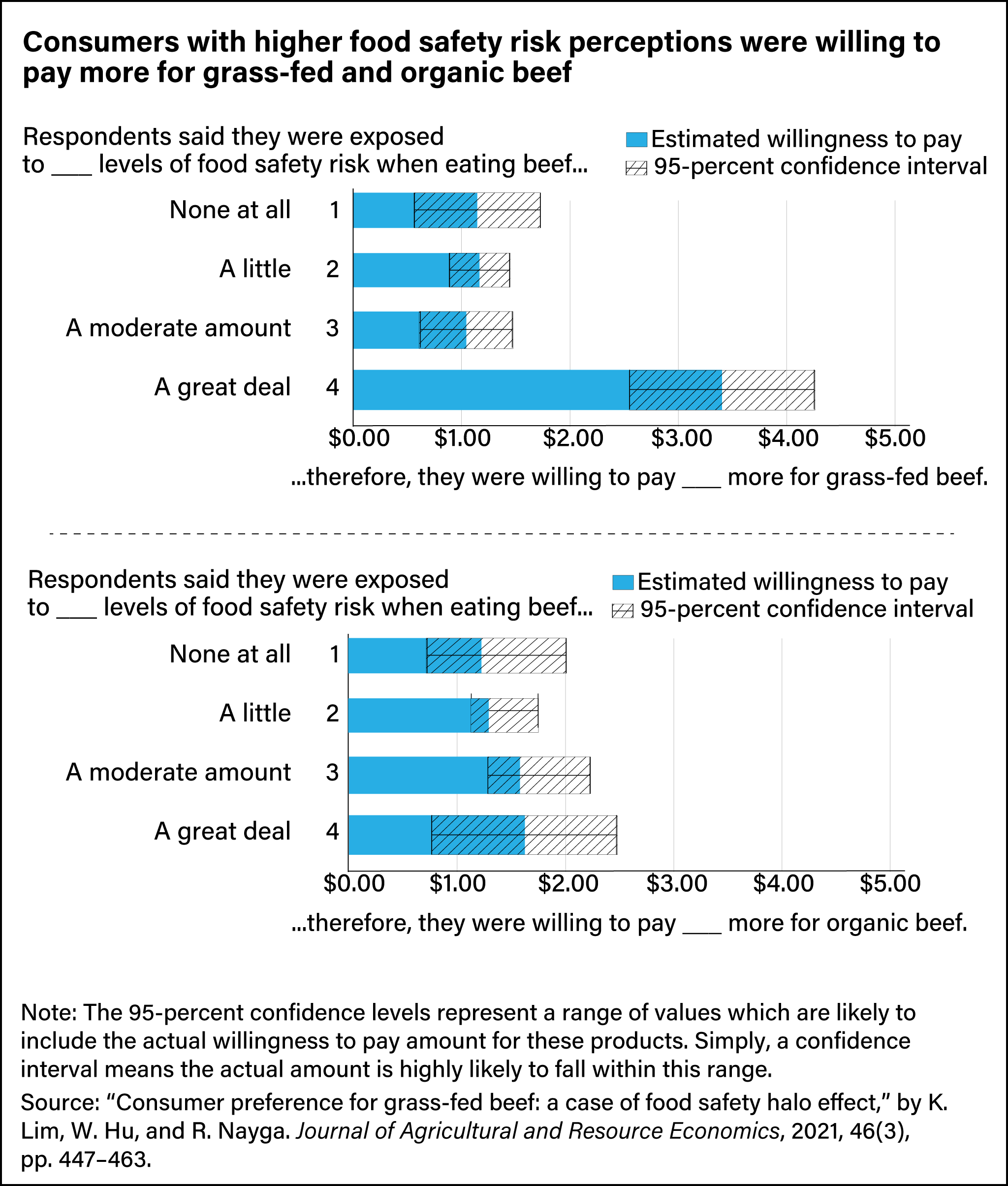

Consumers who perceived the highest risk from eating beef were also willing to pay substantially higher amounts for grass-fed beef. A high-risk perception was associated with a willingness to pay up to $3 more per pound for grass-fed beef compared to conventional beef; whereas those in lower perceived-risk categories were willing to pay only around $1 more. Organic beef exhibited a similar pattern, where the higher risk perception was associated with a higher willingness to pay.

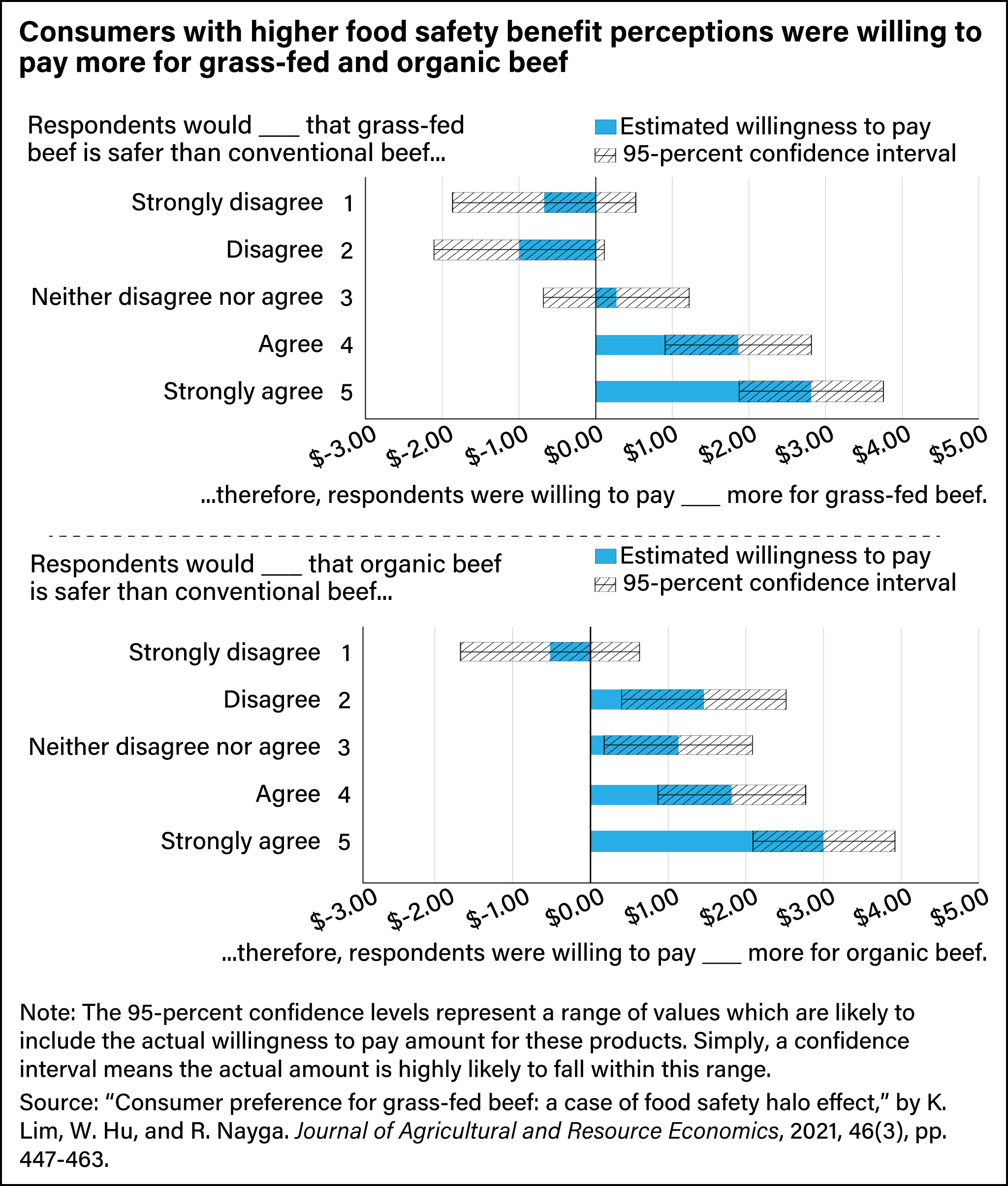

Consumers who perceived grass-fed to be safer than conventional also had a higher willingness to pay. On average, those who agreed or strongly agreed that grass-fed was safer were willing to pay around $2 more per pound, whereas the other groups were generally unwilling to pay more for grass-fed beef. In comparison, a similar pattern was also observed with organic beef.

This study suggests some consumers are drawn to grass-fed beef for perceived food safety, even though the scientific literature is inconclusive as to whether grass-fed is safer than conventional. Regardless of production methods, beef sold in the United States is subject to inspection by USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service under a set of scientifically based food safety criteria.

Food Labels Can Inform Consumers in Different Ways

The use of food labels such as RWA and eco-labels to signal production practices has become a common practice. These labels signal how foods are produced and can impact what consumers buy and how businesses and retailers market products. While food labels serve a role in informing consumers about features of the products, the manner in which labels are interpreted and used remains an open topic for additional research.

Errata: On April 8, 2022, the legend labels of the second figure in this article were revised to correctly reflect "Organic" and "Raised without antibiotics" data.

This article is drawn from:

- Page, E.T., Short, G., Sneeringer, S. & Bowman, M. (2021). The Market for Chicken Raised Without Antibiotics, 2012–17. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-224.

- Lim, K.H., Hu, W. & Nayga, R.M., Jr. (2018). “Is Marine Stewardship Council’s Ecolabel a Rising Tide for All? Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Origin-differentiated Ecolabeled Canned Tuna” . Marine Policy. (96) : 18–26..

- Lim, K.H., Hu, W. & Nayga, R.M., Jr. (2021). “Consumer Preference for Grass-fed Beef: A Case of Food Safety Halo Effect”. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 46(3): 447–463.

You may also like:

- Consumer Information and Labeling - Food Labeling. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Kuchler, F., Greene, C., Bowman, M., Marshall, K.K., Bovay, J. & Lynch, L. (2017). Beyond Nutrition and Organic Labels—30 Years of Experience With Intervening in Food Labels. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-239.