Adoption of Genetically Engineered Dicamba-Tolerant Cotton Seeds is Prevalent Throughout the United States

- by Laura Dodson, Seth J. Wechsler, Sam Williamson, Jonathan McFadden and David Smith

- 7/6/2021

Dicamba is an herbicide used to control annual and perennial broadleaf weeds. In 2016, Monsanto first commercialized genetically engineered (GE) dicamba-tolerant (DT) cotton seeds. The genetic engineering process inserts into a plant’s genome genes with beneficial traits, such as the ability to tolerate herbicide applications. DT cotton varieties were developed by inserting a bacterial gene that enables them to survive dicamba applications. Since 2016, cotton farmers have widely adopted DT cotton seeds.

Weed management is essential to ensure the quality of harvested cotton and to increase farm profit. Most U.S. cotton farmers control weeds using a combination of herbicides—such as pendimethalin, metolachlor, dicamba, 2,4-D choline, glufosinate, and glyphosate—and GE herbicide-tolerant (HT) seeds. As of 2019, GE cotton varieties resistant to glyphosate, glufosinate, 2,4-D choline, or dicamba were commercially available. Most are “stacked” with multiple HT traits, such as glyphosate and dicamba tolerance.

The adoption of dicamba-tolerant seeds is driven by many factors, such as seed costs, alternatives for controlling weeds, yield goals, and regulations that affect the use of dicamba.

USDA and various State-level Department of Agriculture data provide insight into how the effectiveness of chemical alternatives to dicamba affect adoption and how dicamba herbicide regulations vary in cotton-producing States.

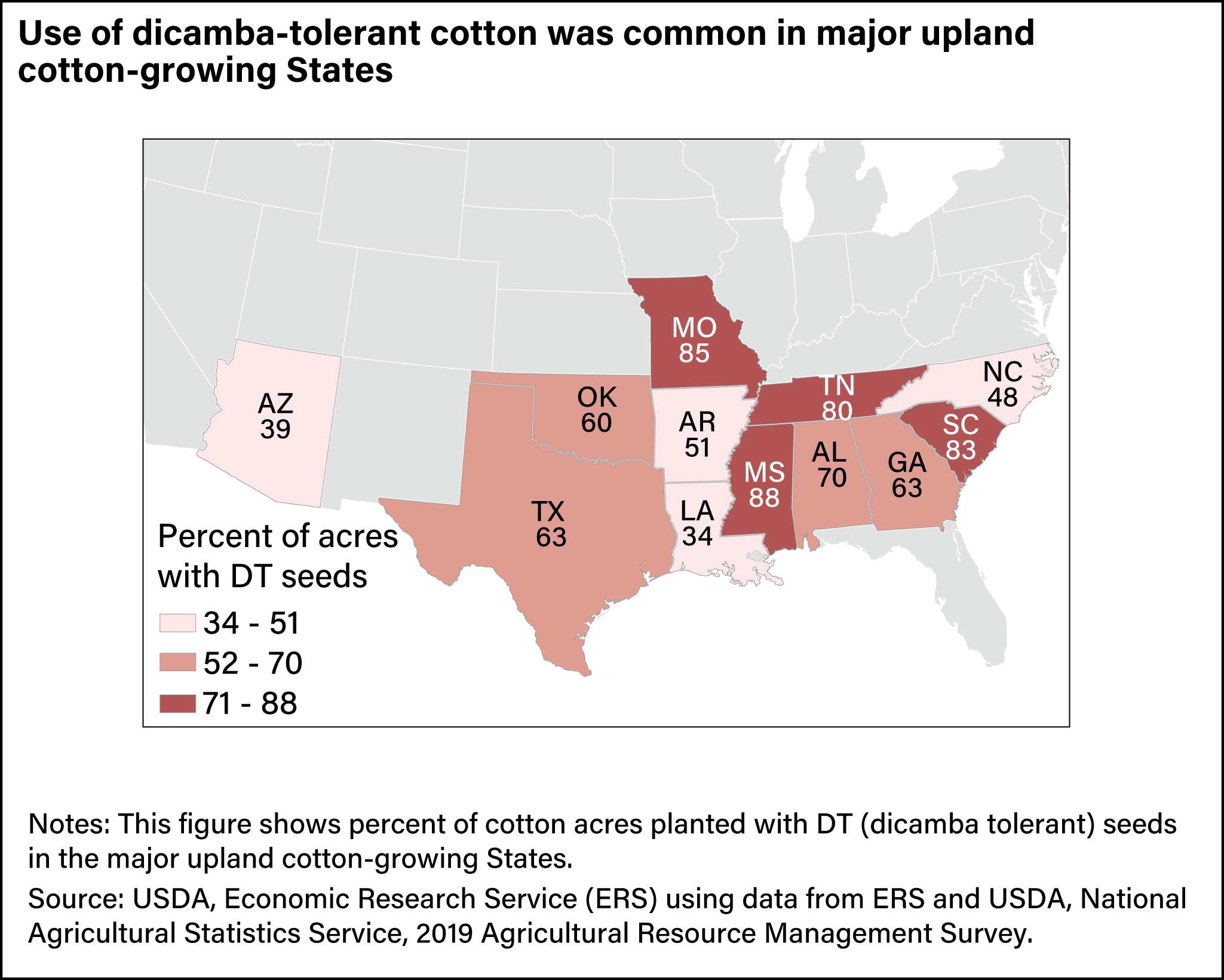

USDA’s 2019 Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) data, which covered the majority of cotton-producing states, suggest that farmers quickly adopted DT cotton seeds. From 2016 to 2019, the percent of cotton acres planted with DT seeds rose from 0 to 69 percent. The States with the most DT seed use in 2019 were Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina, and Tennessee—where approximately 88 percent, 85 percent, 83 percent, and 80 percent of cotton acres were planted with DT varieties, respectively.

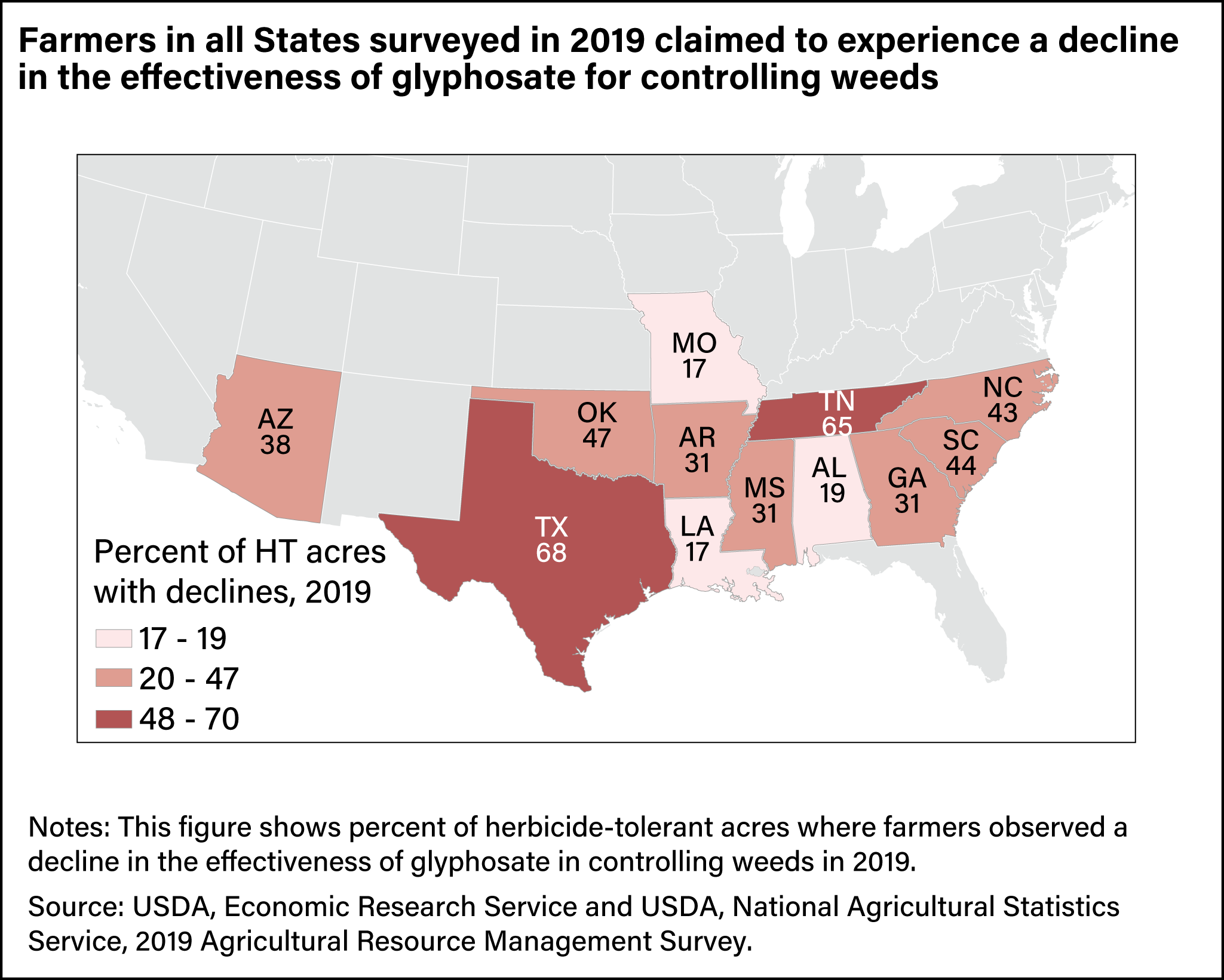

Before the commercialization of DT cotton seeds, farmers had widely adopted GE glyphosate- and glufosinate-tolerant crop varieties. As adoption rates for these HT crops increased, the use of glyphosate and glufosinate increased, particularly glyphosate. On some fields, a small number of naturally resistant weeds, from a small number of weed species, survived (or “escaped”) glyphosate applications. Over time, these weeds bred and spread, passing on their natural resistance to the next generation. By 2019, there were glyphosate-tolerant weeds in the majority of cotton-producing States, leading to a reduction in glyphosate’s effectiveness. Initially, farmers increased glyphosate use to compensate for declines in glyphosate’s effectiveness. As glyphosate resistance worsened, it became profitable for farmers to include additional herbicides, such as dicamba.

ARMS data from 2019 indicated that farmers observed declines in the effectiveness of glyphosate in all States surveyed. Generally, there appeared to be more DT seed where farmers reported a decline in the effectiveness of glyphosate. However, the States with the most glyphosate-resistant weeds were not always the States with the most DT cotton. For example, a decline in the effectiveness of glyphosate was observed on approximately 68 percent of the planted cotton acreage in Texas, but DT seeds were only planted on 63 percent of that State’s cotton acreage.

State and Federal Restrictions

State and Federal restrictions for the use of dicamba can also influence a farmer’s decision to adopt DT seeds. When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved dicamba for post-emergent (“over the top”) use for cotton in November 2016, it included restrictions intended to reduce the risk of dicamba drifting or moving off-target. Nevertheless, there were many reports of crop damage because of off-target movement from DT cotton (and soybeans) in 2016 and 2017. EPA updated these restrictions in 2018 to further minimize the potential for off-target plant damage. In 2019, Federal restrictions included:

- Applications are limited to 1 hour after sunrise and must end 2 hours before sunset. This minimizes the chance of spraying during temperature inversions.

- Applications are limited to 60 days after planting cotton.

- Fields located in areas with endangered plant species must maintain buffers on all sides of the field.

- Only certified applicators who have taken dicamba-specific training may use or handle dicamba products or spraying equipment.

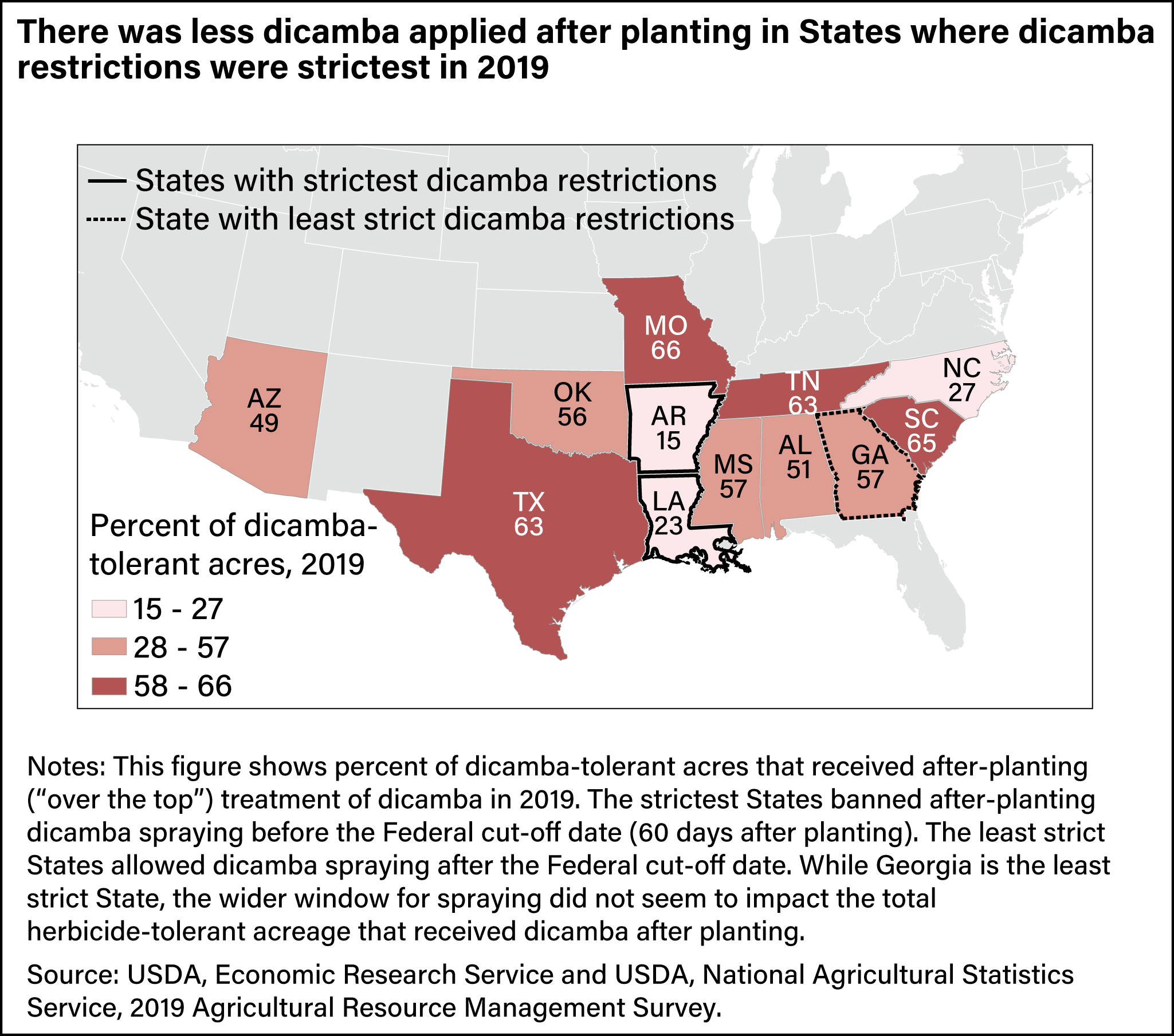

Different States imposed additional restrictions or extensions for dicamba application in 2019. For example, in Arkansas and Louisiana, dicamba could only be applied to cotton early in the growing season when environmental conditions reduce the risk of off-target movement. In contrast, Georgia, Oklahoma, and Texas granted Special Local Need registrations to increase farmers’ flexibility by expanding the dicamba spraying window further into the growing season from the allowed 60 days after planting. In 2020, the EPA instituted a single nationwide cutoff date of July 30. In 2021, EPA notified States that state-issued Special Local Need Registrations that adjust the cutoff date would not be approved.

| State | Planting cut-off date | Typical planting dates |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 60 days after planting | April 24 – May 24 |

| Arizona | 60 days after planting |

April 1 – April 30 |

| Arkansas | May 25 |

April 30 – May 23 |

| Louisiana | June 15 |

April 24 – May 17 |

| Mississippi | 60 days after planting | April 27 – May 19 |

| Missouri | 60 days after planting | April 29 – May 23 |

| North Carolina | 60 days after planting | May 1 – May 20 |

| Oklahoma | 60 days after planting | May 11 – June 10 |

| South Carolina | 60 days after planting | May 1 – May 20 |

| Tennessee | 60 days after planting | May 1 – May 25 |

| Texas | 60 days after planting | April 8 – June 7 |

| Harvest cut-off date | Typical harvest dates | |

| Georgia | 7 days before harvest | Oct. 10 – Dec. 2 |

|

Note: In Louisiana, planting cut-off date applies only to select geographic locations. |

||

Based on the data obtained from the 2019 ARMS Phase 2 Crop Production Practices, in States with earlier dicamba cutoff dates, there appeared to be less dicamba applied “over the top” during the growing season. For instance, in Arkansas and Louisiana, where cutoff dates occur early in the growing season, 16 percent and 23 percent of DT cotton acres were sprayed with dicamba after planting in 2019. By contrast, Georgia allows dicamba spraying until one week before harvest, which can occur as late as December. About 57 percent of DT cotton acres received after-planting applications of dicamba in Georgia in 2019.

This article is drawn from:

- Dodson, L. (2020, December 7). Use of Genetically Engineered Cotton Has Shifted Toward Stacked Seed Traits. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crops in the United States. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Livingston, M., Fernandez-Cornejo, J., Unger, J., Osteen, C., Schimmelpfennig, D., Park, T. & Lambert, D. (2015). The Economics of Glyphosate Resistance Management in Corn and Soybean Production. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-184.

You may also like:

- Biotechnology. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Fernandez-Cornejo, J., Wechsler, S.J., Livingston, M. & Mitchell, L. (2014). Genetically Engineered Crops in the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-162.

- Nehring, R., Osteen, C., Wechsler, S.J., Martin, A., Vialou, A. & Fernandez-Cornejo, J. (2014). Pesticide Use in U.S. Agriculture: 21 Selected Crops, 1960-2008. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-124.