Retail Food Prices Less Volatile Than Farm and Wholesale Prices

- by Gianna Short

- 5/4/2020

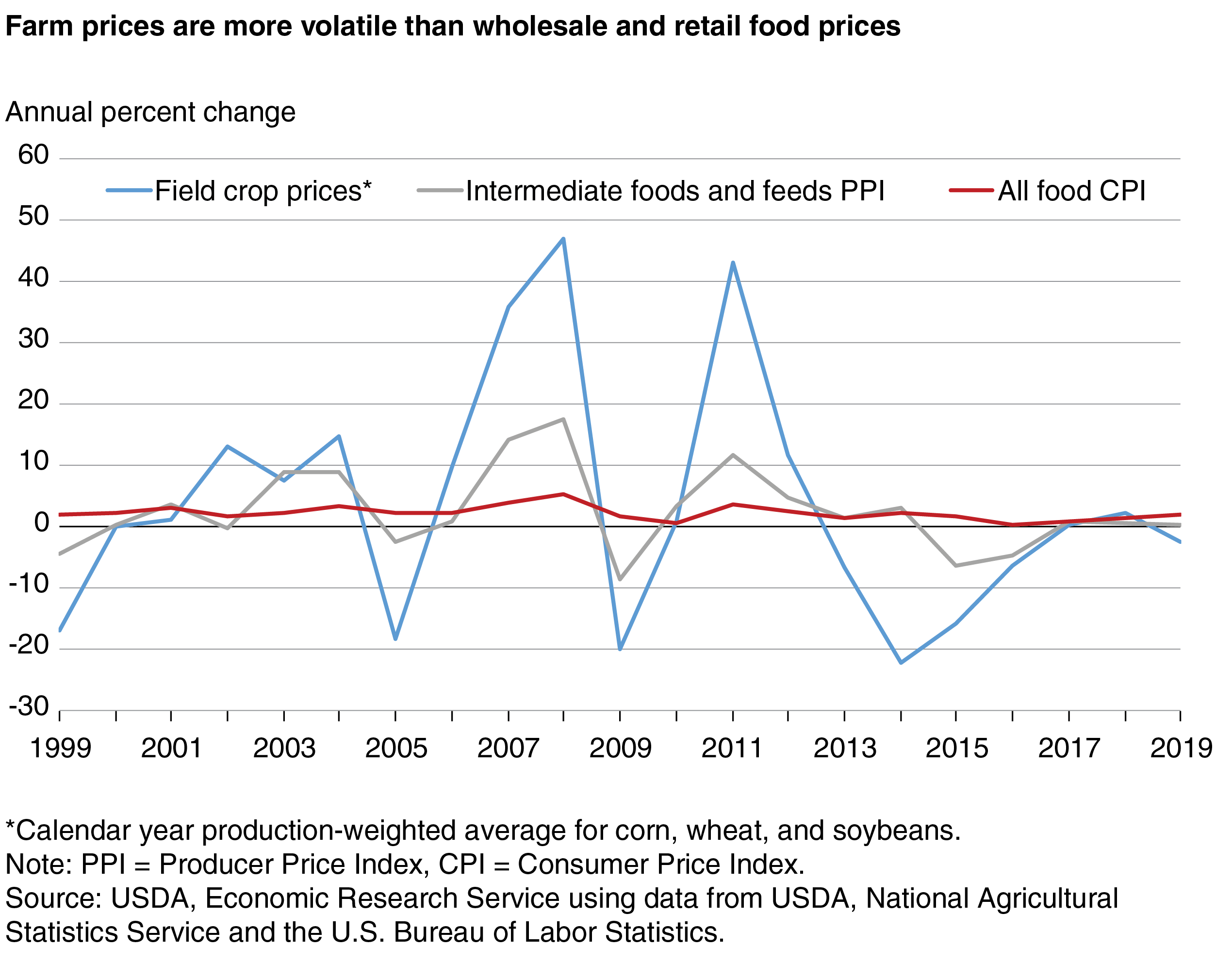

Corn, wheat, and soybeans are the top three U.S. field crops, and they comprise the majority of field crop inputs to the U.S. food supply. The average farm price of these crops, weighted by their production volumes, regularly rises or falls by more than 10 percent from year to year.

However, price changes at the farm level do not always show up on grocery shelves or restaurant menus. Price swings at the farm level have less impact on food prices as food gets closer to the dinner table. For example, the production-weighted farm price of corn, wheat, and soybeans increased by 43 percent in 2011. That same year, the Producer Price Index for intermediate foods and feeds, a category of processed foods such as wheat flour and soybean oil, rose 12 percent. Retail food prices—as measured by the Consumer Price Index for all food (foods purchased in stores and eating places)—rose just 4 percent.

The process of converting farm commodities into consumer foods, such as corn flakes and restaurant meals, adds additional value and requires additional production inputs such as labor, energy, packaging, transportation, and marketing. Thus, farm commodity prices are a small piece of retail food prices, particularly for highly processed products and restaurant offerings. In the past few decades, as processed foods and away-from-home dining became a greater portion of Americans’ diets, the farm (or commodity) share of the foods Americans eat declined. According to the USDA, Economic Research Service’s food dollar statistics, the farm share of a typical dollar spent by consumers on domestically produced food fell from 17.5 percent in 1993 to 14.6 percent in 2018.

Another reason retail food prices tend to be less volatile than farm and wholesale prices is the structure of the grocery retail industry, with large grocery store chains often competing for consumers’ food dollars by keeping prices low. To help achieve low prices, large retailers might use marketing contracts to give them more control over the wholesale products they purchase. These contracts put retailers in a better position to smooth price spikes and keep retail food prices more stable.

Thus, while the relationship of price shocks being passed from the farm to the grocery store shelf has intuitive appeal, it does not tell the full story. When forecasting retail food price changes, the retail environment and consumer demand factors are important components that also must be considered. Both of these factors—the food retailing environment and consumer demand for food—are being affected by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying shelter-in-place restrictions. The data presented in this article predate the COVID-19 pandemic and do not reflect its shocks to food demand and the U.S. food system.

This article is drawn from:

- Food Price Outlook. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Food Dollar Series. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.