Much Like Other Americans, Veterans Would Benefit From Improving the Quality of Their Diets

- by Hayden Stewart and Diansheng Dong

- 2/3/2020

Highlights

- Veterans and nonveterans could improve the quality of their diets by consuming more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dairy, as well as by cutting back on added sugars and solid fats.

- Being a veteran is associated with slightly lower diet quality after controlling for economic and demographic differences between veterans and nonveterans.

- Veterans acquire a somewhat higher share of their calories from solid fats and added sugars than do nonveterans.

In 2018, 18 million U.S. men and women—about 7.1 percent of the U.S. adult population—were veterans; they had served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces, Reserves, or National Guard. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates a variety of programs for these former service men and women, including ones that focus on nutrition and diet quality. Consuming a healthy diet promotes wellness and is associated with lower healthcare costs. The VA pairs veterans with registered dietitians and other nutrition professionals who can provide them with nutrition education and counseling at VA healthcare facilities. Veterans and their families can also learn about health and nutrition at one of the VA’s Healthy Teaching Kitchens. Some facilities offer cooking demonstrations, while others offer hands-on participation.

ERS researchers recently used self-reported food intake data to assess veterans’ diets and how their diets compare with those of nonveterans. The researchers found that, much like other Americans, veterans do not follow many of the recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, jointly published every 5 years by USDA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. After controlling for demographic differences between veterans and nonveterans, such as that veterans tend to be older and are more often male, the researchers found veterans to have somewhat lower quality diets than nonveterans. Added sugars and solid fats accounted for a larger share of all calories consumed by veterans as compared with nonveterans.

Healthy Eating Index Can Be Used To Score Diet Quality

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends the amount of food individuals should consume from different food groups (vegetables, fruits, protein, dairy, grains, and liquid oils), as well as from subgroups such as dark green vegetables and whole grains. Recommended quantities for food groups are scaled to account for differences in caloric needs, which depend on an individual’s age, gender, and level of physical activity. For example, individuals consuming 2,000 calories per day are advised to eat 2.5 cup-equivalents of vegetables and 6 ounce-equivalents of grains per day, whereas individuals consuming 3,000 calories per day are advised to consume 4 cup-equivalents of vegetables and 10 ounce-equivalents of grains per day.

To assess how well an individual’s diet aligns with key recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines, USDA and the National Cancer Institute developed the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). The index is scored from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a healthier diet. Individuals’ diets are evaluated on a density basis (i.e., the amount of a dietary component consumed divided by total calories). This approach allows for a common standard across individuals for whom recommended quantities differ and captures the balance among foods consumed.

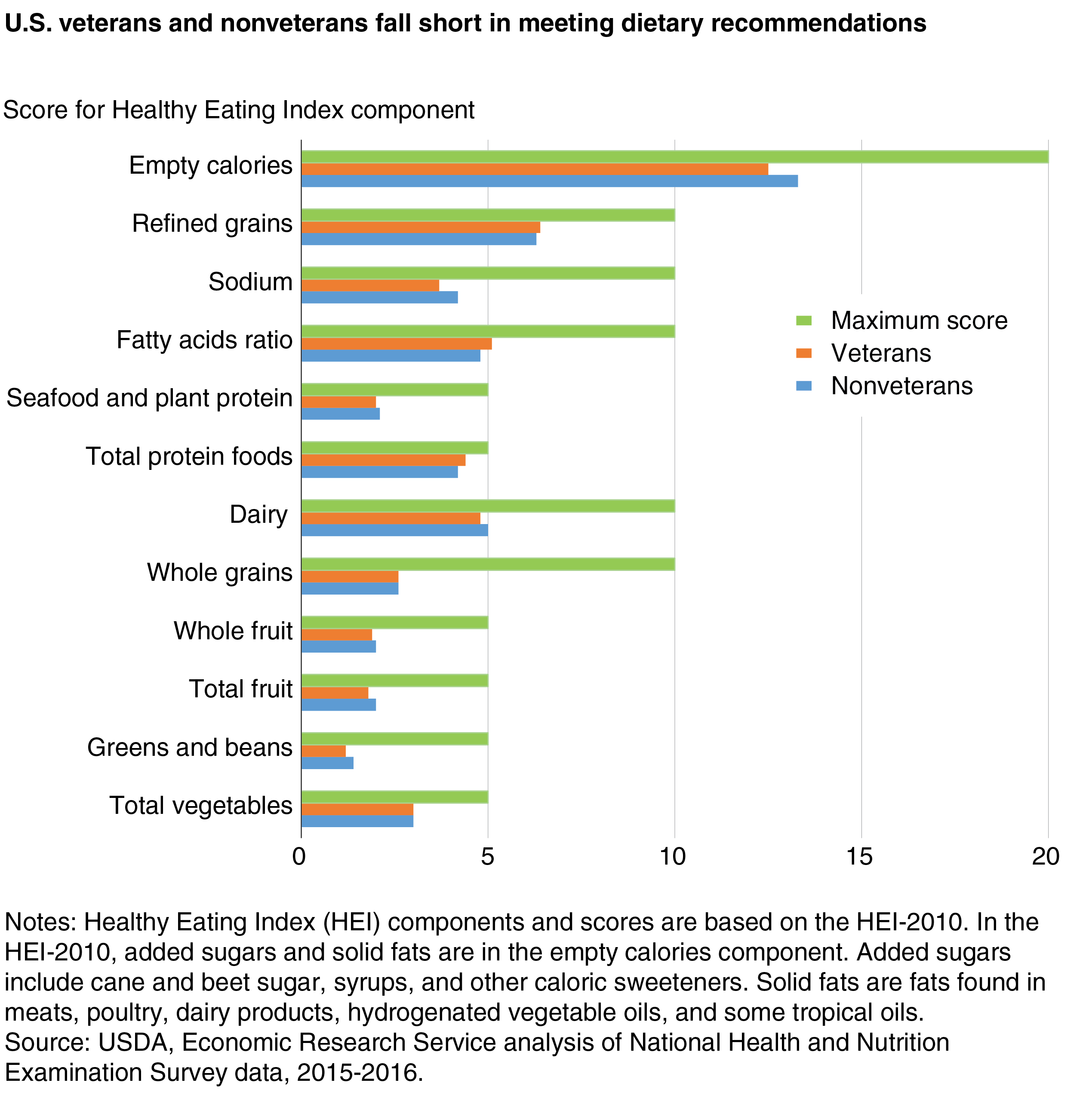

An individual’s overall HEI score is calculated by summing 12-13 component scores, which measure how well the person satisfies recommendations for specific food groups and subgroups. For example, the component score for total vegetables ranges from a maximum of 5 for individuals who most closely follow recommendations for vegetable consumption to a minimum of 0 for those who consume no vegetables. As another example, an individual who obtains a smaller share of total calories from added sugars would earn a higher score for this empty calories component than a person for whom added sugars make up a larger share of total calories. (Added sugars include cane and beet sugar, syrups, and other caloric sweeteners, but not naturally occurring sugars such as those in fruits and milk.)

Previous studies tend to show that most people do not closely follow the Dietary Guidelines, but some groups do better than others. Older adults, for example, generally do better than younger and middle-aged adults. Women tend to follow the Dietary Guidelines more closely than men. Education is also positively associated with diet quality, meaning individuals with more years of formal schooling generally have higher HEI scores than people with fewer years of schooling.

Veterans’ Diet Scores Much Like Other Americans’ Scores

ERS researchers used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to assess veterans’ and nonveterans’ diets. Each year about 5,000 individuals participate in the survey, which includes a food intake module. Individuals participating in that module complete two 24-hour dietary recalls on nonconsecutive days in which they provide a detailed description of each food and beverage consumed—and the amounts consumed—during the previous 24 hours. This information can be matched with an individual’s age, race, household income, veteran status, and other demographic characteristics as captured in the broader NHANES. One question asks NHANES participants whether they have ever served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces, military Reserves, or National Guard. Prior active duty is defined in NHANES to exclude training for the Reserves or National Guard, but to include activation for service in the United States or in a foreign country in support of military or humanitarian operations.

ERS researchers calculated average HEI scores using day 1 dietary intake data for veterans and nonveterans for each of seven surveys (2003-04, 2005-06, 2007-08, 2009-10, 2011-12, 2013-14, and 2015-16). Total HEI scores for the two groups were similar, averaging around 50 (out of 100) for both veterans and nonveterans over the period. Veterans’ diet quality showed a slight improvement over time from 2005 to 2012, but a small decrease from 2013 to 2016. Much like other Americans, veterans consume too many empty calories from added sugars and solid fats given their reported calorie intake, while their consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dairy products is below recommended amounts. Among all HEI component scores in 2015-16, veterans received the lowest share of all possible points for their consumption of dark green vegetables and beans (1.2 out of 5), whole grains (2.6 out of 10), and total fruit (1.8 out of 5).

Veterans Get More of Their Total Calories From Added Sugars and Solid Fats

Differences in average HEI scores reflect a variety of characteristics for veterans besides military service, such as that veterans tend to be older and are more likely to be male as compared with the population at large. In the NHANES surveys, veterans were 58.6 years old on average versus 44.4 years old for the nonveterans. Less than 10 percent of the NHANES veterans were women. To isolate the impact of being a veteran on diet quality, ERS researchers used a statistical model to control for economic and demographic differences between the two groups. Their model reveals that veterans have worse diet quality, all else constant. After adjusting for economic and demographic differences, veterans attained an average total HEI score of 45.6 over the study period versus 49.3 for nonveterans

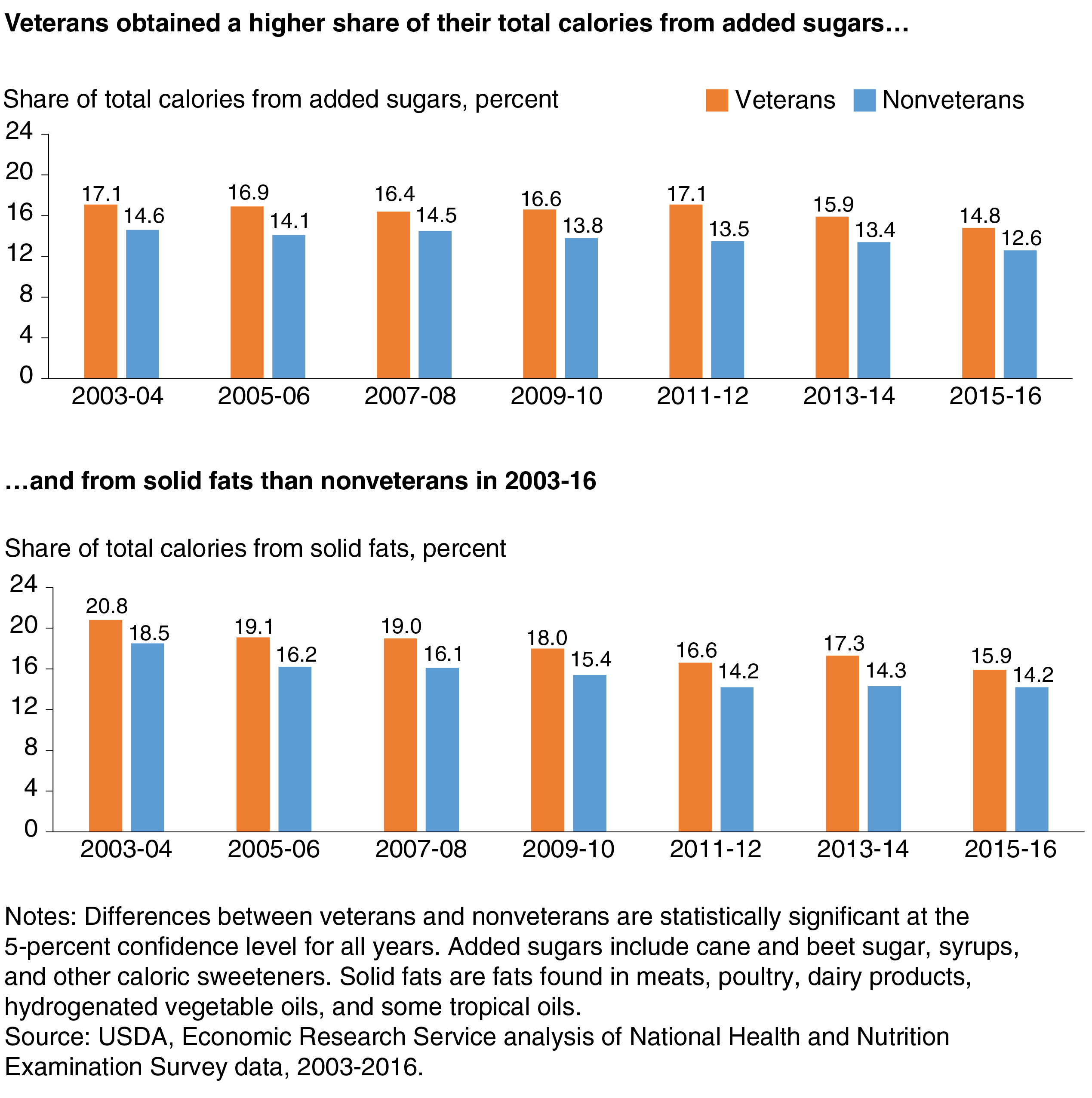

Veterans’ lower average total HEI score, adjusted for economic and demographic differences, is primarily due to a higher percentage of their calories coming from less-nutrient-rich added sugars and solid fats. (Solid fats are the fats found in meats, poultry, dairy products, hydrogenated vegetable oils, and some tropical oils.) The largest difference for calories from added sugars was in 2011-12. In that period, added sugars accounted for 17.1 percent of adjusted total calories for veterans and 13.5 percent for nonveterans. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans encourages individuals to keep calories from added sugars below 10 percent of total calories. For calories from solid fats, the largest difference was in 2013-14, when solid fats accounted for 17.3 percent of adjusted total calories for veterans and 14.3 percent for nonveterans.

Future research is needed to identify why veterans rely more on added sugars and solid fats than nonveterans. One possibility is that people who choose to participate in military service may share characteristics that are associated with food choices and diet quality. For example, individuals who were more physically active in their childhoods—and able to consume more calories without putting on excess weight—may be more likely to enlist in the military as young adults. Alternatively, military service may have shaped their eating habits. Their physically active jobs may have encouraged military personnel to consume higher calorie foods during their years of service—eating habits that may continue after they leave military service.

This article is drawn from:

- Dong, D., Stewart, H. & Carlson, A. (2019). An Examination of Veterans’ Diet Quality. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-271.

You may also like:

- Mancino, L., Guthrie, J., Ver Ploeg, M. & Lin, B. (2018). Nutritional Quality of Foods Acquired by Americans: Findings From USDA’s National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-188.