Partially Completed Conservation Contracts Reveal On-Farm Practice Incentives

- by Steven Wallander and Kelly B. Maguire

- 4/6/2020

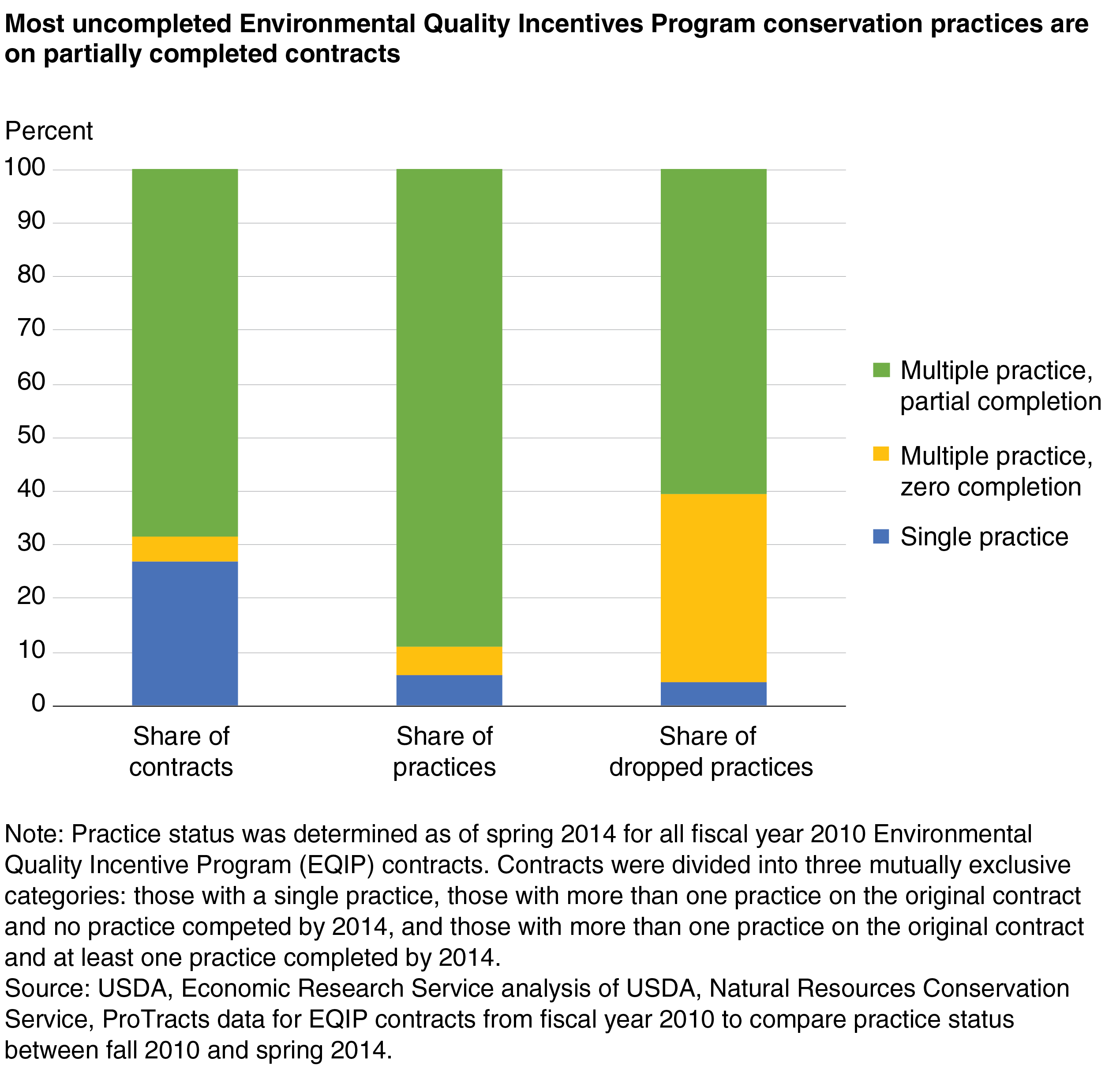

Each year, as part of the working lands conservation programs, USDA signs thousands of contracts with farmers and ranchers who agree to implement conservation practices. Within the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), these voluntary agreements stipulate specific practices that the farmer or rancher will carry out in exchange for technical and financial assistance. Some of these contracts are simple—in 2010, about 25 percent of EQIP contracts consisted of only a single practice, such as using conservation tillage to improve soil health or installing a livestock waste management facility. Most of the contracts, though, are complex and contain multiple practices.

Overall, EQIP contracts are highly successful: about 80 percent of conservation practices signed in 2010 were completed as originally specified by 2014. The loss of the 20 percent of practices that were dropped from the contracts can be administratively burdensome and costly, so understanding why farmers and ranchers don’t carry out practices may help improve the way the program is designed.

ERS researchers examined the relationship between contract structure and practices that are completed versus those that were dropped. Simple contracts with only a single practice represented 5 percent of all practices on contracts signed in 2010, and slightly less than 5 percent of all practices dropped by 2014. Complex contracts that were entirely cancelled or terminated contained 35 percent of all of the practice dropped (by 2014) even though those same contracts only represent 5 percent of all practices (completed and dropped by 2014). However, the largest share of dropped practices—almost 60 percent—occurred on complex contracts where at least one of the originally planned practices was completed as planned.

Partially completed contracts reflect the interconnected nature of the partnership between USDA and farmers or ranchers that is central to working lands conservation programs. Given the mixture of resource concerns on a particular plot of land, the practices generally must simultaneously provide on-field benefits to the farmer or rancher and also public benefits (often off-field) that justify USDA’s expenditures on financial assistance. When these multiple benefits come from different practices on the same contract, it can lead to uneven incentives to finish the practices.

One possible explanation for partially-completed contracts is that program participants may be putting multiple practices on a contract to boost their ranking so they are more likely to obtain an EQIP contract. Once they receive a contract, these participants may then drop practices that are less effective at providing on-field benefits. While additional analysis of the data provides some evidence of this behavior, it appears to be limited in scope—likely because of the rigorous conservation planning process involved in designing contracts.

Another explanation is that dropped practices reflect changes in environmental and market conditions over the term of the contract. For example, a drought can make it more costly to implement certain practices. When this happens, practices with the lowest on-farm benefits are more likely to be dropped. While current program structure gives USDA the flexibility to modify contracts by replacing practices, it does not provide much flexibility to adjust financial assistance levels during a contract if market conditions change, except when financial assistance is based on actual practice expenditures.

Overall, ERS researchers found that most contracts were completed as planned. For the fifth of practices that were dropped, only about 40 percent occurred where the entire contract was cancelled or terminated. The fact that the majority of dropped practices were on partially completed contracts shows that farmers’ incentives to complete practices can vary within a contract. Knowing more about the relationship between the types of benefits and dropped practices may help policymakers and program managers improve the efficiency of the program.

This article is drawn from:

- Wallander, S., Claassen, R., Hill, A. & Fooks, J.R. (2019). Working Lands Conservation Contract Modifications: Patterns in Dropped Practices. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-262.

You may also like:

- Wallander, S. & Claassen, R. (2019, June 3). Conservation Practices With Greater Benefits to Farmers and Ranchers Have Higher EQIP Completion Rates. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.