The 2012-13 U.S. Drought Heightened Federal Disaster Assistance Payments for Livestock Producers

- by Matthew MacLachlan, Sean E. Ramos and Ashley Hungerford

- 5/7/2018

Federal livestock disaster programs assist producers facing risks that are introduced through the natural environment. The Federal Government has typically designed individual programs to address distinct sources of environmental risk. In recent history, widespread, severe, and persistent drought affected grazing livestock throughout much of the United States. Decreased forage availability stresses animals, increases costs, and leads producers to slaughter animals earlier than they otherwise would.

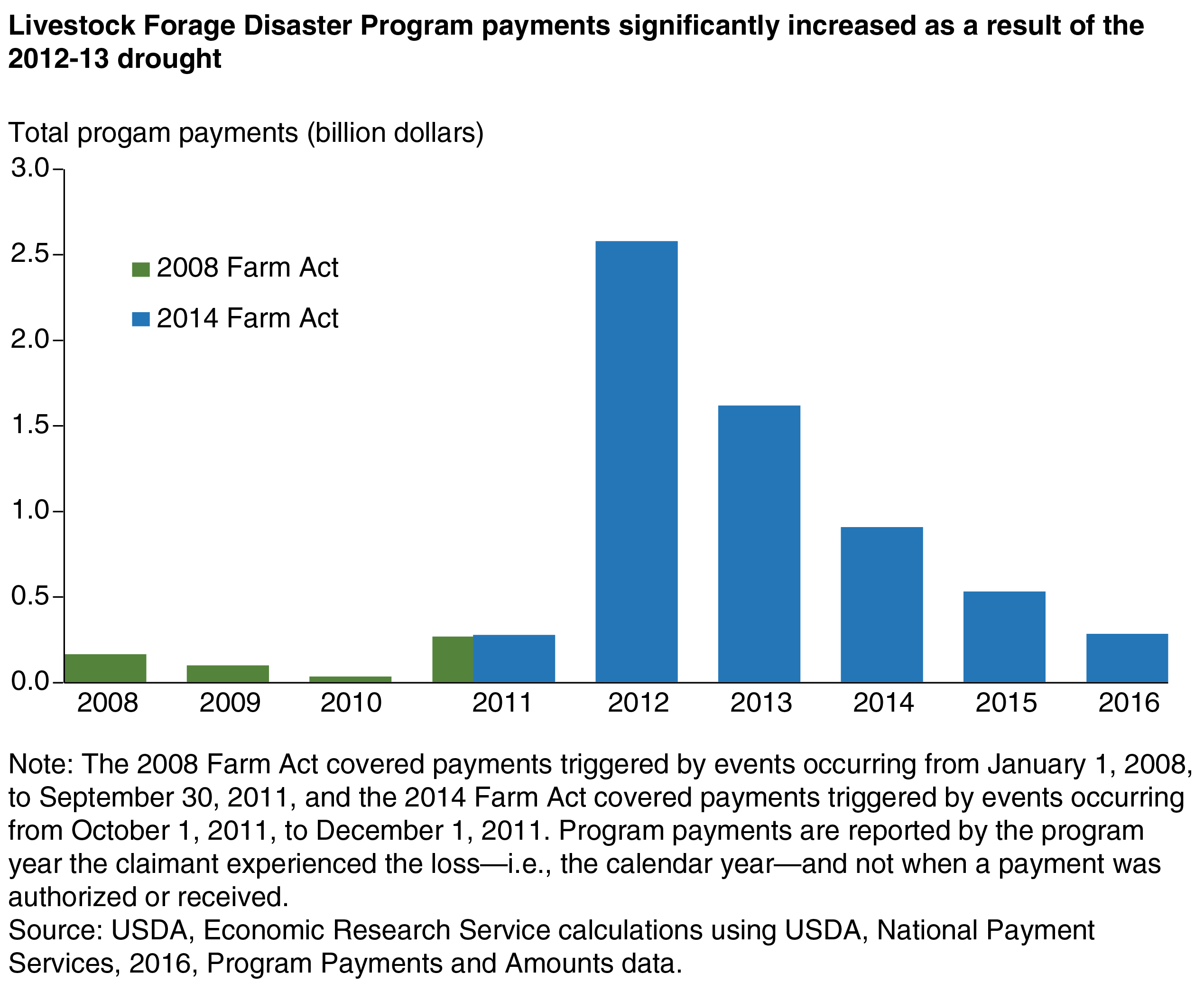

ERS researchers recently examined four livestock disaster assistance programs administered by USDA. Among these programs, the Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP) is the largest in terms of total outlays. LFP provides payments to eligible producers when the grazing capacity of their land has been reduced by qualifying drought or wildfire.

During 2012 and 2013, a historic drought weakened production across many agricultural products throughout much of the United States. The poor conditions directly affected livestock production—particularly cattle production—by reducing the availability of water and the quality of pasture land. The drought also increased the costs of feed used in place of pasture. These adverse conditions likely contributed to declines in livestock production, particularly in the regions most affected by the drought.

The drought began just after authorization to operate LFP lapsed. The 2008 Farm Act established LFP to partially offset increased costs from droughts and wildfires that degraded the quality of pasturelands, but authorization to continue the program expired on October 1, 2011. The compensation provided by LFP had been used to ease hardships caused by drought or fire. For example, the 2012-13 drought increased costs not covered under a disaster assistance program, leading to a higher rate of slaughter.

Lawmakers renewed LFP in the 2014 Farm Act, with several key changes and provisions. For example, the 2014 Farm Act authorized retroactive payments for losses experienced after the lapse of LFP in 2011 to alleviate hardships experienced by affected producers. The 2014 Farm Act made LFP permanent to avoid future lapses in the program’s authorization, particularly during extreme weather events. Relaxation of qualification requirements likely allowed more producers to receive payments. On average, producers also received increased compensation per natural disaster experienced. These changes together contributed to significant increases in program expenditures, particularly to cover costs incurred during the 2012-13 drought, which were paid retroactively after LFP’s renewal, as well as for 2014-15 to a much lesser extent.

This article is drawn from:

- MacLachlan, M., Ramos, S.E., Hungerford, A. & Edwards, S. (2018). Federal Natural Disaster Assistance Programs for Livestock Producers, 2008–2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-187.