Veterans Are Positioned To Contribute Economically to Rural Communities

- by Tracey Farrigan

- 9/5/2017

Veterans are a rapidly aging and increasingly diverse group disproportionally represented by rural Americans. Nearly 19 million veterans lived in the United States in 2015; about 3.4 million of them were located in rural areas. Examining data from the U.S. Census Bureau can reveal information about who they are, where they live, the type of work they do, and how they fare economically. This information can help policymakers and others to better align veteran and community needs.

Veterans Are a Diverse Group With Diverse Needs

The U.S. Census Bureau classifies veterans based on when they last served in the military, not where—regardless of whether they were on active duty prior to that date. The majority of veterans who served since September 2001 are Post-Draft Era or All-Volunteer Force (AVF) veterans, as are a small share who served before that date. The AVF began in 1973, so most AVF veterans are working age (18 to 64 years old), while most Draft Era veterans are 65 years or older. In 2015, about 45 percent of rural veterans were working age; the rest were elder veterans.

Differences in military structure, enlistment policy, and national demographic trends between working-age and elder veterans make each group distinctively unique. For instance, elder veterans are predominantly male (98 percent in 2015) and white non-Hispanic (92 percent). By comparison, working-age veterans are more diverse, with a larger and growing female (12 percent) and racial/ethnic minority (17 percent) presence.

Where Veterans Live Reflects Who They Are

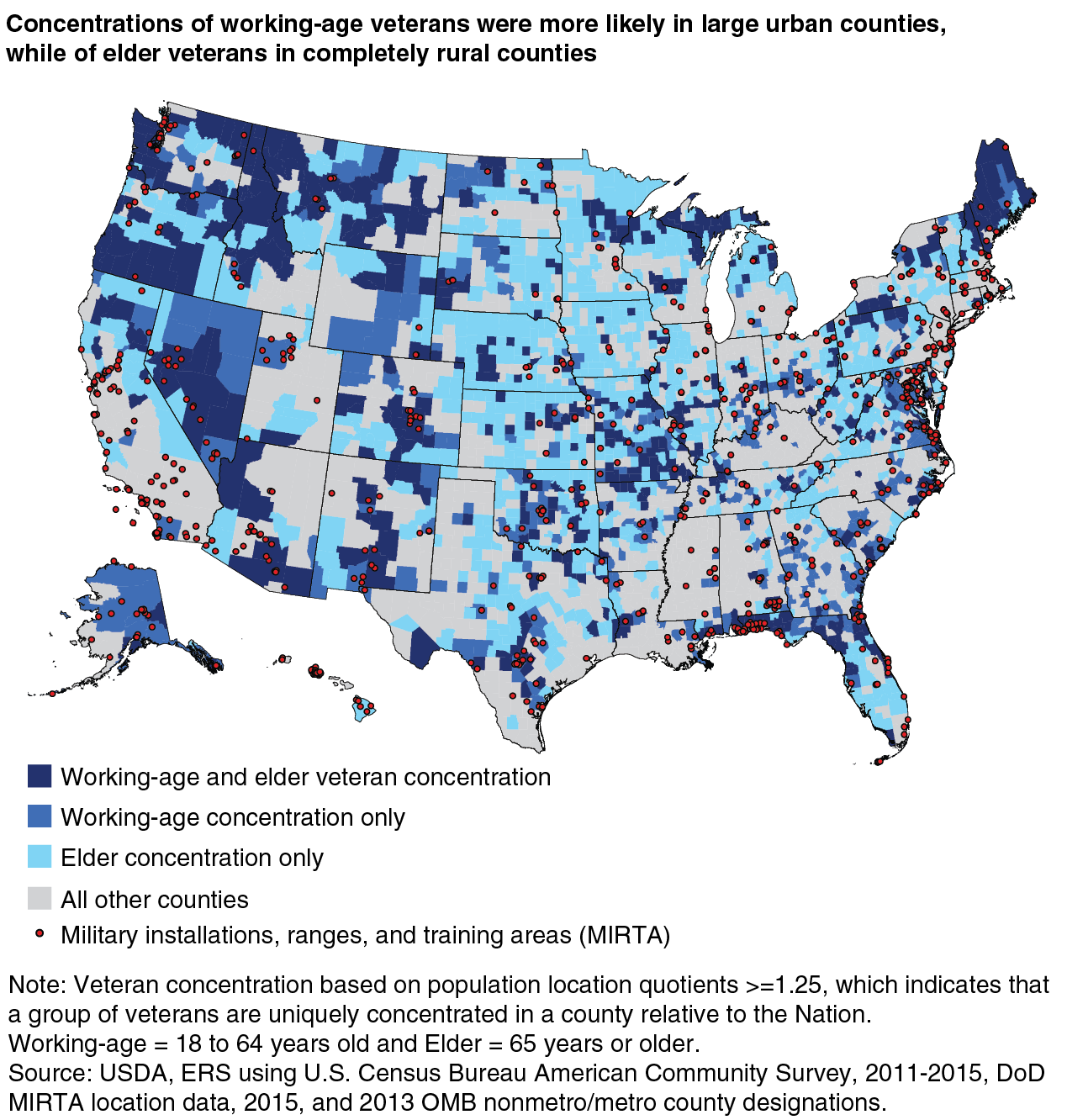

Veterans are overrepresented in rural America. Nearly 18 percent of veterans live in rural (nonmetro) counties, compared to 15 percent of the U.S. adult civilian population. About 10 percent of all rural civilian adults are veterans, but in some rural counties that figure can reach as high as 25 percent. The U.S. counties with the highest share of veterans tend to have significantly larger shares or concentrations of elder veterans relative to the Nation as a whole. Those counties are characteristically different than the ones with working-age veteran concentrations as discussed below using ERS Rural Classifications, which measure rurality in detail and assess the economic and social diversity of rural America.

Working-age and elder veterans are concentrated in counties with different characteristics. Areas with concentrations of working-age veterans are predominantly large urban counties (28 percent of all U.S. counties). By comparison, areas with concentrations of elder veterans are more likely to be completely rural counties not adjacent to metro areas (24 percent). Areas that contain concentrations of both groups are mostly rural counties adjacent to metro areas (19 percent). Many of these counties contain or neighbor military installations, reserve bases, or training areas.

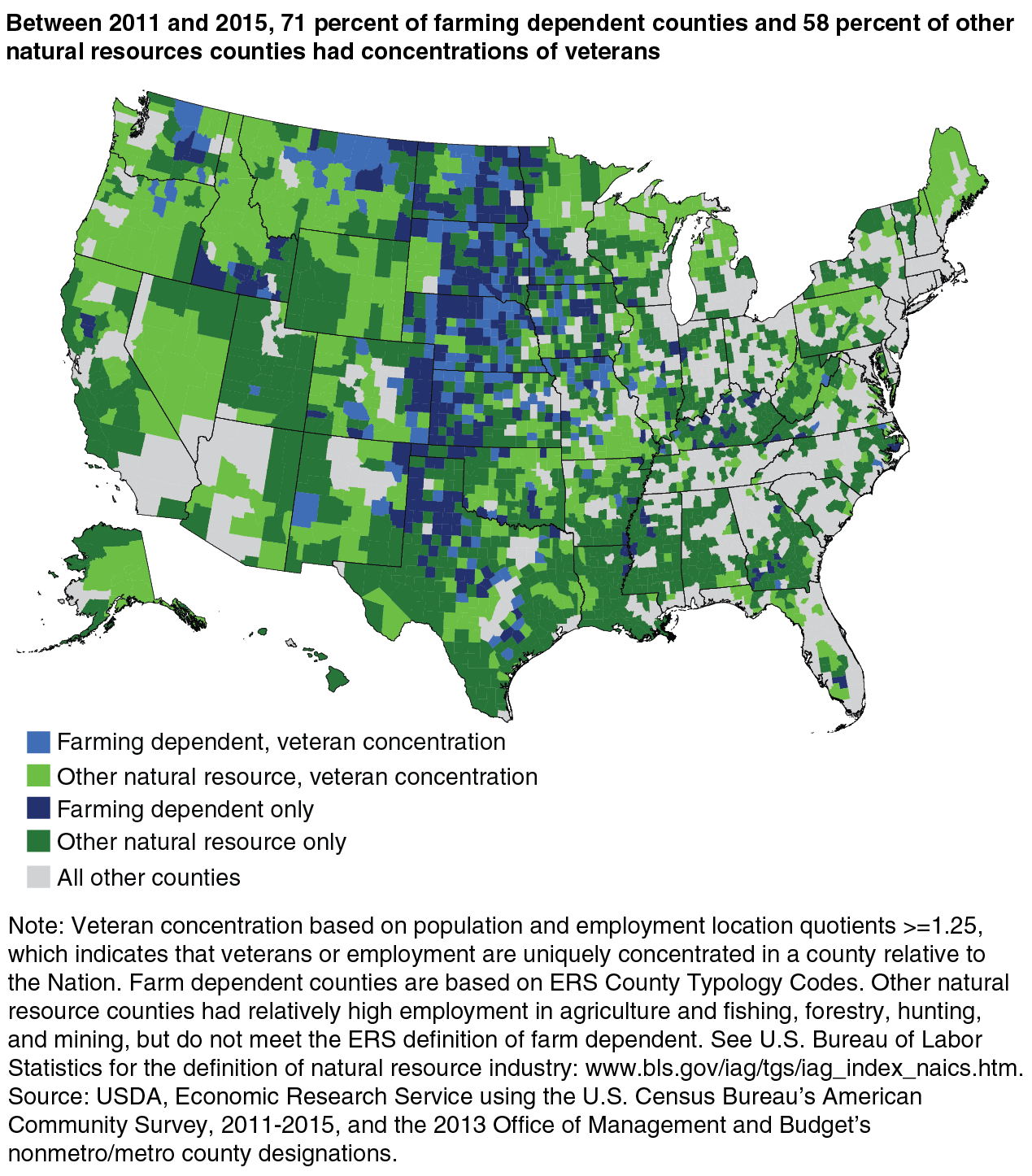

The regional concentration of rural veterans varies with a county’s economic dependence, as classified by the ERS County Typology Codes. In 2015, there were 444 farming-dependent counties (88 percent rural), and 71 percent of them had concentrations of veterans. By comparison, there were 1,714 other natural resource counties (78 percent rural) and nearly 58 percent of them had concentrations of veterans. Other natural resource counties had high employment relative to the Nation in agriculture and fishing, forestry, hunting, and mining—but do not meet the ERS definition of farm dependent. (See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics for the definition of natural resource industry.)

However, the concentrations within these counties also varied with the type of veteran. Of farming dependent counties, about 4 percent had concentrations of working-age veterans, 56 percent had concentrations of elder veterans, and 11 percent had concentrations of both types. Of the natural resource counties, on the other hand, about 10 percent had working age, 30 percent had elder, and 18 percent had concentrations of both veteran types.

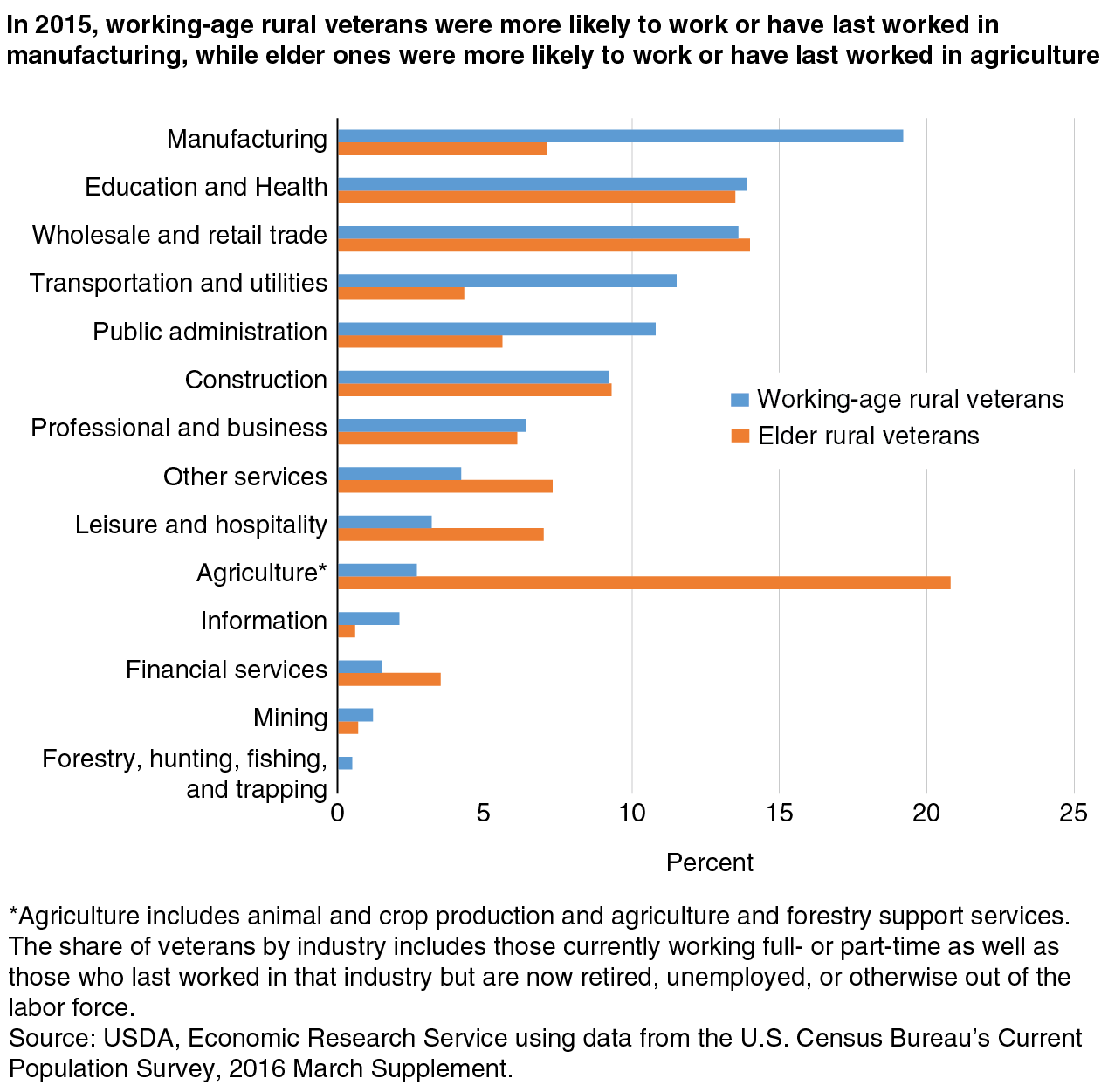

Elder Veterans Relied More on Agriculture for Employment, While Working-Age Veterans Relied More on Manufacturing

In 2015, elder rural veterans were more likely than working-age veterans to be attached to the agricultural industry through their current or most recent past employment. As a whole, elder veterans were also more likely to be self-employed farmers or ranchers; their younger cohorts were more likely to be wage and salary earners working in support services for crop and animal production. Overall, about 21 percent of elder rural veterans reported currently working (full- or part-time) or having last worked (if retired or unemployed) in the agriculture industry. By comparison, less than 3 percent of working-age veterans reported the same. Instead, working-age veterans relied more on the manufacturing industry for employment. About 19 percent of working-age veterans reported currently working or having last worked in manufacturing, compared to 7 percent of elder veterans.

Veterans Fare Better Economically Than Nonveterans

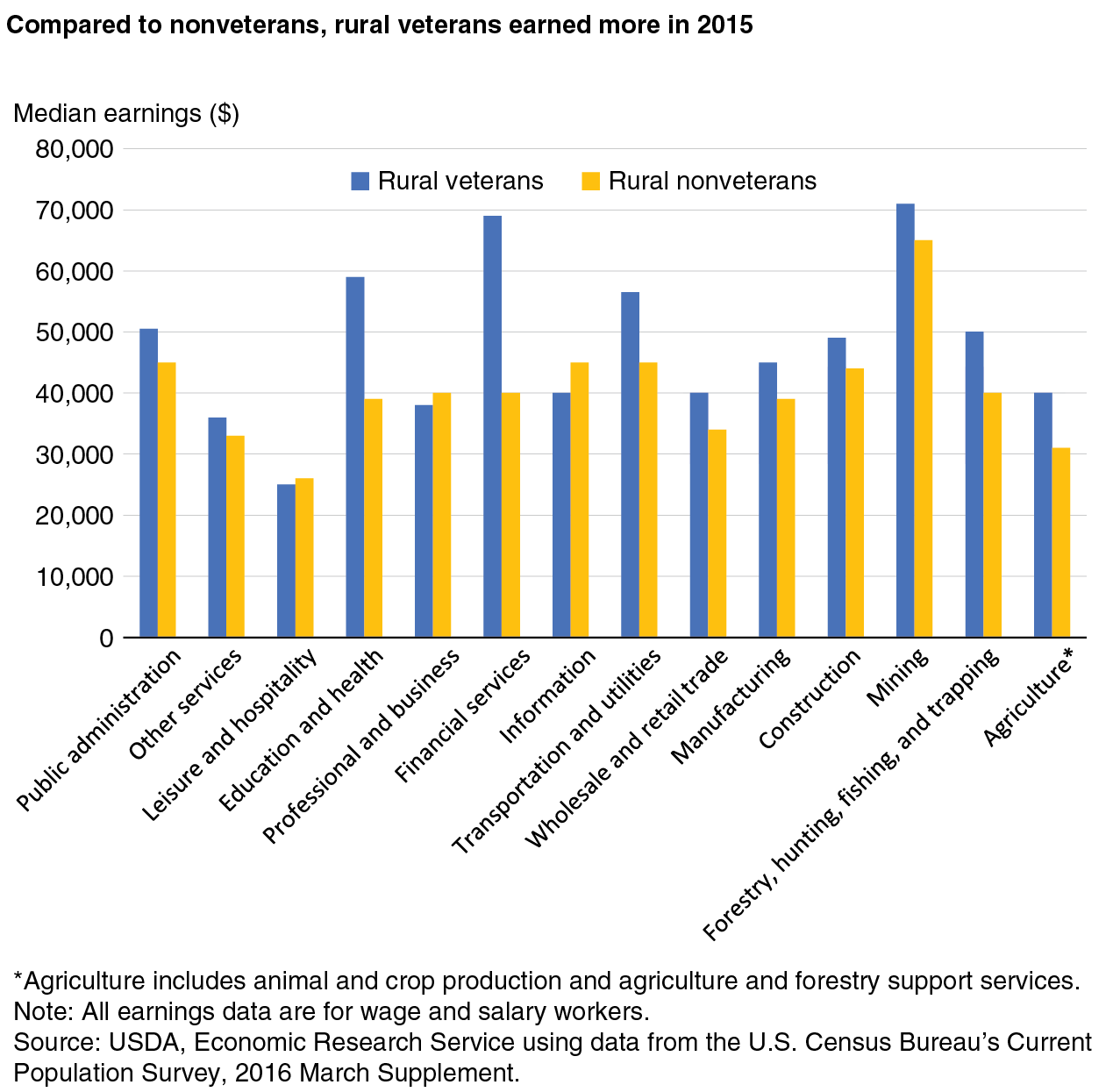

Veterans have much to contribute to rural communities. Veterans returning home from active duty, as well as those who move to rural communities as newcomers, add to the population base and increase the demand for goods and services. Veterans tend to have more education on average and can benefit their communities by contributing their leadership, technical, and entrepreneurial skills. These advantages are some of the reasons that veterans have lower poverty rates and higher earnings compared to nonveterans.

In 2015, rural veterans who were full-time wage and salary workers had median earnings of about $50,000. That’s $11,000 more than the median earnings of their nonveteran counterparts. Earnings for veterans and nonveterans varied by industry, however. For example, compared to nonveterans in 2015, the median earnings of veterans was $29,000 higher in financial services, $4,500 higher in public administration, and $1,000 lower in leisure and hospitality.

Differences in median earnings by industry between veterans and nonveterans track closely with educational attainment. However, even in industries where fewer veteran than nonveteran earners had a college degree in 2015, the median income for veterans was near or greater than that of nonveterans. This may be explained by a variety of factors, including differences in demographic composition and job skills. For example, veterans are older and predominantly male, and thus on average more likely to have higher earnings than the general population.

This article is drawn from:

- Atlas of Rural and Small-Town America. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Farrigan, T. & Cromartie, J. (2013). Rural Veterans at a Glance. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EB-25.

You may also like:

- County Typology Codes. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Rural Classifications. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.