Federal Nutrition and Organic Labels Paved the Way for Single-Trait Label Claims

- by Fred Kuchler, Catherine Greene, Maria Bowman, Kandice K. Marshall, John Bovay and Lori Lynch

- 11/17/2017

Highlights

- National standards for organic products and nutrition information have yielded credible, truthful labels about multiple product characteristics, but consumers are often confused about what the information means.

- Many producers and food companies have opted for less comprehensive, single-trait label claims, such as “raised without antibiotics,” in response to consumer demand.

- Single-trait claims also provide incentives for producers and firms to change their production processes and supply more choice in the marketplace.

Consumers have influenced the evolution of food policy in the United States for over a century. For example, USDA meat inspection laws emerged in the early part of the 20th century in response to mounting consumer concerns about the safety of meat products—concerns awakened by Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel, The Jungle. Other early USDA food labeling laws focused on grades and standards for color, size, and other food attributes that consumers can verify by looking at, buying, or eating the product. During the second half of the 20th century, consumers became interested in the “credence attributes” of food—attributes or qualities that consumers cannot easily verify on their own. For example, a new generation of environmentally conscious consumers emerged in the 1970s that was interested in foods produced in ways that were healthier for themselves and the planet.

Consumer interest in credence attributes has continued to expand during the last few decades. Larger segments of consumers care, for example, about how crops are grown and whether livestock are humanely raised. This demand is driven by considerations of personal health, animal welfare, environmental impacts, and other factors. In response, companies have added a lot of information about health and production methods to their packaging. Consumers now face a profusion of claims, including “natural,” “low-sodium,” “cage-free,” “heart healthy,” and “non-GMO” (does not contain genetically modified organisms).

Labels can provide valuable information for consumers, increase demand for producers’ products, and permit new product attributes to be marketed. However, label claims can potentially mislead or confuse consumers, providing an economic rationale for the Federal Government and private sector groups to set and enforce standards for claims to ensure that consumers receive useful, reliable information. The various labeling interventions carry costs and benefits, as revealed by the history (now spanning several decades) of setting standards for credence attribute labels, certifying their accuracy, and enforcing their appropriate use.

Federal Regulations Tackle Complex Information on Nutrition and Organic Practices

In 1990, Congress passed two watershed labeling laws that required Federal agencies to develop standards for several credence attributes. The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA) required the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop standardized information about a product’s nutrient content, and the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 (OFPA) required USDA to set national standards for the production, processing, handling, packaging, and labeling of organic foods, including development of the USDA Organic seal. NLEA was implemented by requiring product nutrient information on most packaged foods. Participation in USDA's organic regulatory program, on the other hand, is voluntary. Products are not required to carry the USDA Organic seal, but those that do must meet the national standards.

The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990

In the 1980s, Government and public health institutions were concerned about the quality of the American diet. The 1988 Surgeon General’s report, for example, described the poor quality of the diets of many Americans and the negative consequences for their health. Prior to NLEA, companies were only required to list the product’s name, net quantity, ingredient list, and manufacturer’s name and address on packaged foods. When nutrition information was included, it was provided in a way that was difficult for many consumers to interpret because of the specialized terminology and units used.

FDA’s stated objectives for implementing NLEA were to reduce consumer confusion about labels, help consumers make better food choices, and give manufacturers an incentive to improve the nutritional quality of foods. NLEA aimed to improve Americans’ diets by requiring standard information about a product’s nutrient content—the extensive Nutrition Facts label—on the back of almost every food package. NLEA also allowed food manufacturers to make some front-of-package health and nutrition claims, such as “high fiber,” “reduced calories,” and “cholesterol free,” while controlling what could be claimed about each food. FDA issued final regulations for NLEA on January 6, 1993, and the rule became effective the middle of the following year. USDA issued similar regulations for meat and poultry products.

The Nutrition Facts label includes information on many nutritional attributes and reflects recommendations from the Federal agencies that are charged with giving dietary advice to consumers. For example, Federal agencies recommend that consumers, for health reasons, minimize their consumption of trans fats, and beginning in 2006, the Nutrition Facts label has included the grams of trans fats per serving. ERS research found a marked decline in the trans fats content of new food products from 2005 to 2010, as food manufacturers reformulated many of their products to eliminate or reduce trans fats.

NLEA has been credited with reducing misleading nutrition label claims, but the overall effect of NLEA on Americans’ diets has been mixed. NLEA was initiated and revised in a period in which consumers’ diets were demonstrably poor and the share of overweight and obese Americans was increasing. Americans held increasingly sedentary jobs, while food became easier to access and was increasingly consumed away from home—purchased from restaurants where there were no labels. These forces have strongly challenged NLEA’s ability to achieve improvements in diets and health.

The Organic Foods Production Act of 1990

Organic agriculture developed early in the 20th century as an alternative to conventional production systems that depend on synthetic chemical inputs. Organic systems place more emphasis on soil quality, nutrient cycling, and plant health. Before implementation of USDA organic regulations, State governments and private-sector nonprofit organizations were the main sources of organic standards. Because of certifier disagreements, varying standards posed a problem for labeling multi-ingredient processed foods, and enforcement was negligible.

OFPA aimed to level the playing field for organic producers, assure consumers that organic products met a consistent standard, and facilitate interstate shipment by creating a uniform organic standard and requiring third-party certification to ensure compliance. OFPA directed USDA to set national standards for organic production and processing. The wide range of production and processing attributes covered under the USDA standards encompasses everything from soil health, farm-level biodiversity, and pasture for ruminants to prohibitions on the use of genetic engineering, antibiotics, hormones, and most synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

Research associates organic practices with a variety of environmental benefits relative to conventional practices, including reduced pesticide residues in food and water, reduced nutrient pollution, improved soil tilth and organic matter, lower energy use, carbon sequestration, and enhanced biodiversity. These benefits come at a cost; consumers pay a higher price for most organic products. USDA expected that setting national organic standards and requiring third-party certification would thwart fraudulent claims and improve producer access to markets.

Organic production has increased rapidly since the national standard was implemented in 2002, and industry analysts report that U.S. organic food sales grew over 15 percent annually during the 2000s, prior to the downturn in the U.S. economy in 2008. In 2016, the Nutrition Business Journal estimated U.S. organic retail food sales at $40 billion, up nearly 9 percent from the previous year. In contrast, the Economic Research Service estimated that growth for all U.S. at-home retail food sales was 2.9 percent in 2016. A recent Economic Research Service analysis found that organic sales accounted for 6-7 percent of total U.S. retail sales of eggs and top fresh fruits and vegetables in 2014 and 14 percent of retail milk sales.

Federal Standards Engage Stakeholders and Require Ongoing Verification and Enforcement…

Federal rulemaking to set national food labeling standards can be time-consuming and requires ongoing agency resources. However, Federal rulemaking allows pursuit of social goals—such as assisting consumers to make healthful food choices—and multiple agencies can collaborate on uniform standards. Federal rulemaking also engages consumers, expert groups, and other stakeholders to help develop consensus-based standards. Competing interests of stakeholders usually involve tradeoffs when developing national standards.

The Federal Government also establishes how label claims will be verified and enforced as part of setting national standards. For the USDA Organic seal, State and private organizations are accredited by USDA to certify organic producers and food handlers. Certifying agents review organic operation plans, conduct annual onsite inspections, and have the authority to investigate and suspend or revoke certifications—and to report violations to USDA. Certifying agents conduct periodic testing for prohibited substances, such as pesticides and genetically engineered materials. Organic operations that falsely sell or label a product as organic are subject to civil penalties of up to $11,000 per violation. USDA has taken disciplinary action against thousands of operations and levied nearly $1.9 million in civil penalties during fiscal 2015.

FDA does not pre-authorize labels, so food manufacturers are responsible for making sure that what they list on the Nutrition Facts label is true. FDA does some directed sampling, usually based on consumer or competitor complaints. When FDA has evidence that information on a Nutrition Facts label is incorrect, enforcement activity usually begins with a warning letter to the manufacturer. While a false front-of-package claim can be identified, it is harder to prove that a claim is misleading.

…But Many Private-Sector Label Claims Do Not

As consumer interest in farming practices and food processing methods continues to expand, producers and food processors are developing their own food label claims. In contrast with the comprehensive and complicated requirements for the Federal nutrition and organic labels, many private-sector food label claims are for a single farming or food processing practice—such as products made from animals that were “raised without antibiotics,” “natural” products, or “non-GMO” products made without genetically modified ingredients. Some companies obtain third-party verification from USDA, nonprofit organizations, or other groups for their label claims, but such verification is not mandatory.

When companies create their own product definitions and standards, the label information may not be consistent, truthful, or understandable. Several major food companies, for example, responded to consumer concerns about antibiotic use in livestock by offering products bearing the label “raised without antibiotics.” However, the companies used different definitions for the same claim. Although these label claims emerged more quickly than with Federal rule-making to set standards, consumers did not understand the differences between the companies’ claims.

USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) requires companies to obtain approval before making certain types of claims related to how an animal is raised on a meat or poultry product. Each company must provide supporting documentation to FSIS for the animal raising claims they plan to use as part of a label. In the late 2000s, FSIS clarified its definition of what it means for firms to use “no antibiotics ever” or to raise animals without antibiotics following a legal dispute between major poultry companies. However, firms continue to be allowed to make other antibiotic-use label claims so long as they follow FSIS policies. For example, USDA verifies alternative claims on the limited use of antibiotics, such as the claim that antibiotics are to prevent and treat illness, but not to promote animal growth.

“Natural” is another example of a single-trait claim that some companies include on the labels of their meat products. FSIS allows food manufacturing companies to use the term “natural” on labels of products under its jurisdiction if artificial ingredients are not added during processing, the product is only “minimally processed,” and the firm puts this definition beside or on the same panel as the “natural” claim. The FSIS definition does not apply to the inputs and methods used during production. For example, the term “natural” can be added to most fresh chicken products even if the chickens were given antibiotics and fed grain that was conventionally produced using pesticides. However, research studies show that many consumers believe the natural claim also refers to the inputs and methods used during production. FDA has a similar policy to allow the term “natural” on food labels, although the FDA web site notes explicitly that its policy is not intended to address the use of pesticides, production practices, or food processing methods.

Regulation of Federal and Private-Sector Food Label Claims Provides Economic Insights

The United States now has many years of real-world experience with private-sector and Federal labeling activity. This experience provides insights about the tradeoffs and other economic effects when the Federal Government intervenes—or chooses not to intervene—in food labeling.

Simple and understandable labels are often at odds with complex information. The comprehensive and complicated requirements for both the Nutrition Facts label and the USDA Organic seal illustrate the fundamental tradeoff between presenting information that is simple and understandable versus nuanced and complex. In addition to what is required by the Nutrition Facts label, food manufacturers have experimented with simplified forms of labels that contain nutrition and health information. These types of claims have proliferated, which may suggest that the information provided by the Nutrition Facts label is too complex for many consumers. According to FDA, consumers like the time-saving feature of front-of-packaging labeling, but find the plethora of labels confusing. These labels may also give consumers an overrated view of a food’s healthfulness, and decrease the likelihood that they will read the Nutrition Facts label.

Voluntary labels rely on consumers to infer negative characteristics. Mandatory labels, such as the Nutrition Facts label, may include negative aspects of foods (high in saturated fat), but voluntary labels will not. Some consumers know how to use the Nutrition Facts label to choose a healthy diet, but the relative healthfulness of various types of nutrients is lost on many. Still, competitive food companies will overcome some of consumers’ limitations by making front-of-package claims that highlight healthy aspects of their products, especially when rival products cannot make the same claim. Consumers might then infer the positive and negative aspects of foods from the presence and absence of label claims. However, if all foods of a particular type contain, for example, trans fats (a shared negative aspect), then no company has an incentive to make front-of-package claims.

Food label claims can create financial incentives for producers to change their production processes. Consumer demand for food produced under farming systems that rely on crop rotations, pasture, and other production processes—rather than antibiotics, hormones, synthetic pesticides, or fertilizers—has increased U.S. retail sales of foods bearing the USDA Organic seal. Demand by consumers for single traits also provides financial incentives for producers to change production practices and advertise the fact through the product’s label. Offering a single trait, such as “raised without antibiotics,” can often be achieved at a lower cost than meeting the multiple production and processing attributes, including the 3-year transition time, required to use the USDA Organic seal. For example, as many as 30-40 percent of broiler chickens could be raised without any antibiotics by the end of 2017, following announcements by several leading poultry companies that they plan to raise all birds without antibiotics (with the exception of the small share that get sick and require treatment).

Federal standards can limit marketplace variety and innovation. Regulations requiring specified label information come at the cost of ruling out competing standards or different product attributes. One standard exists for all products regardless of the variation in consumer preferences, and the hidden costs are reduced marketplace variety and innovation. For example, the Nutrition Facts label provides information designed for an average individual and cannot offer information designed for a specific individual’s dietary needs. Producers and food companies can voluntarily exceed the Federal standard, but Federal standards often do not offer a way for them to advertise the higher attributes. If a producer or company cannot promote this higher attribute, it is unlikely to spend the resources to develop and supply the attribute.

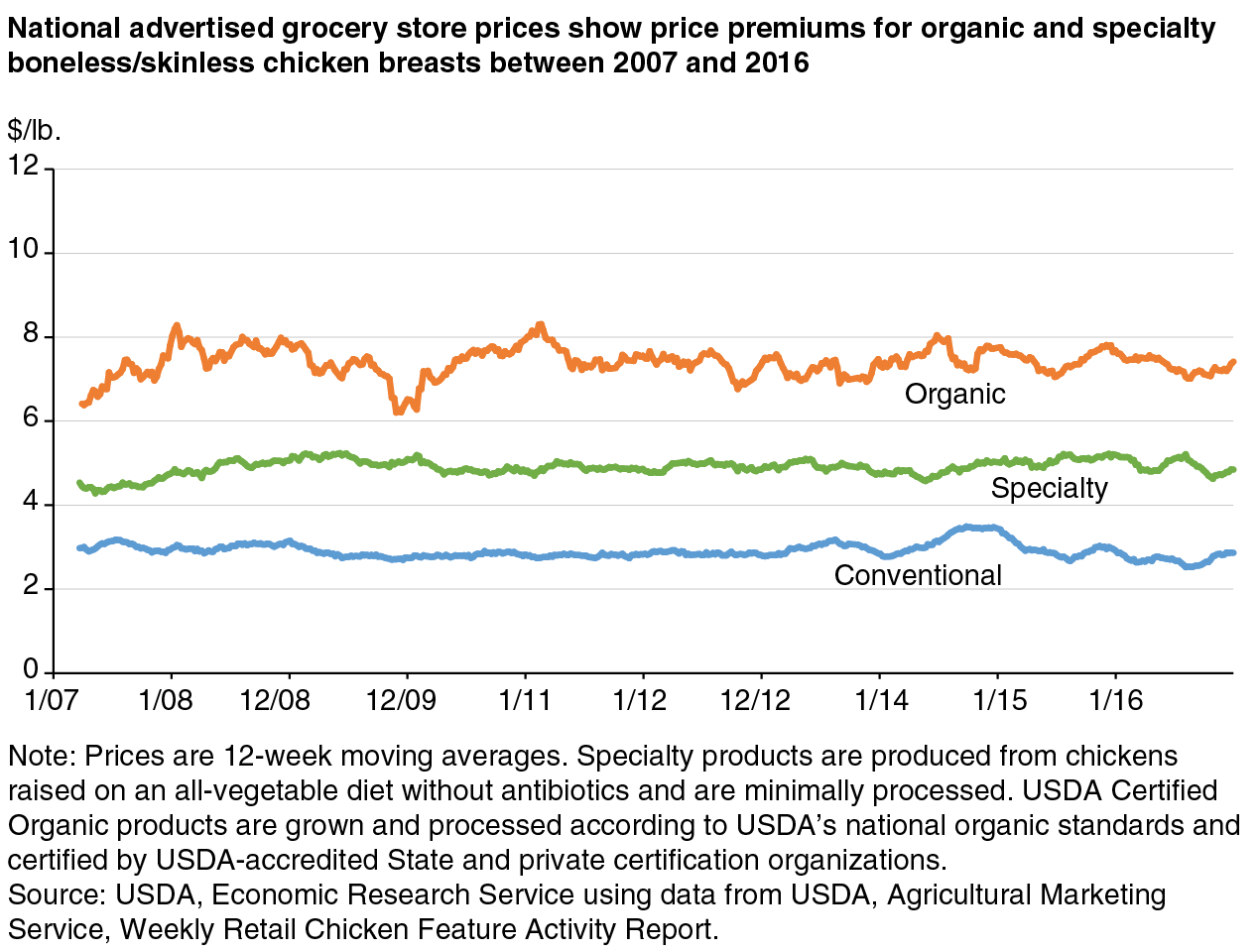

Single-trait labels can provide more choice in the marketplace. “Raised without antibiotics,” “non-GMO,” and other single-trait label claims provide consumers more choice in the marketplace. Products making single claims generally have smaller price premiums than products grown and processed according to USDA’s multiple organic standards. For example, average advertised prices for chicken breasts from certified organic animals were approximately 170 percent higher than conventional chicken breasts during 2016, while breasts from animals raised without antibiotics averaged about 80 percent higher. Smaller price premiums for single-trait products expand the market of potential customers for nonconventional products.

Consumers are often confused about label claims. Given that a variety of antibiotic-use claims are allowed on products, it is not clear whether FSIS’s requirements for claims implying no antibiotic use, such as “raised without antibiotics” or “no antibiotics ever” have made the label claims more understandable to consumers. Many consumers also misinterpret the poorly defined “natural” claim, believing it covers multiple attributes the way the USDA Organic seal does. A 2015 Consumer Reports study found that nearly two-thirds of consumers surveyed believed that “natural” meant that no artificial growth hormones were used; 59 percent believed that it meant that animals were fed feed that did not contain genetically engineered ingredients; and 57 percent believed that it meant that no antibiotics or other drugs were used.

New information platforms may not be reducing consumer confusion over label claims. One outcome of the digital revolution has been the advent of numerous information platforms that offer details about the healthfulness and environmental attributes of various food products. However, this information may vary widely in truthfulness, credibility, and scientific support. Some information and claims are not altogether different from the way patent medicines were aggressively marketed to consumers in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, efficacy did not have to be proven, and doctors did not control access. Manufacturers made any therapeutic claims for their products that they wished.

While quickly conveying new nutrition research to average consumers and those with specialized needs, the new information platforms can also compete with the scientifically robust information in the Nutrition Facts label for consumers’ attention. This competition for consumers’ attention could potentially diminish the influence of the Nutrition Facts label and other federally regulated labels. Challenges to food label policies will continue as producers, food companies, and policymakers strive to provide accurate and informative food labels that are understandable to consumers.

This article is drawn from:

- Kuchler, F., Greene, C., Bowman, M., Marshall, K.K., Bovay, J. & Lynch, L. (2017). Beyond Nutrition and Organic Labels—30 Years of Experience With Intervening in Food Labels. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-239.

You may also like:

- Greene, C., Ferreira, G., Carlson, A., Cooke, B. & Hitaj, C. (2017, February 6). Growing Organic Demand Provides High-Value Opportunities for Many Types of Producers. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Rahkovsky, I., Martinez, S. & Kuchler, F. (2012). New Food Choices Free of Trans Fats Better Align U.S. Diets With Health Recommendations. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-95.