Growth in Inflation-Adjusted Food Prices Varies by Food Category

- by Annemarie Kuhns

- 7/6/2015

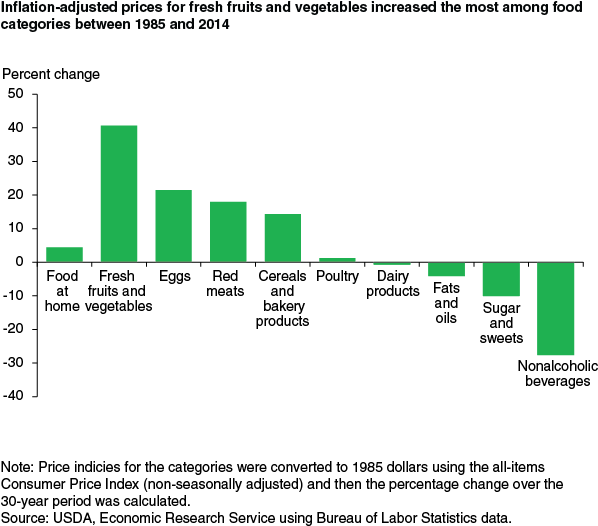

Over the past 30 years, grocery store prices have risen 4.5 percent above economy-wide prices, indicating that food has become relatively more expensive than some other consumer goods. Retail food (food at home) inflation outpaced overall inflation because food prices largely depend on commodity prices and transportation costs, which have risen sharply over the last three decades. Inflation-adjusted (real) prices for poultry and dairy products have increased roughly the same as overall inflation, while real prices for eggs and red meats grew by 21.5 and 18 percent between 1985 and 2014, respectively.* Real prices for fresh fruits and vegetables grew the most among all major food categories, increasing just over 40 percent.

Retail prices for fresh fruits and vegetables, eggs, and meats are more strongly linked with commodity prices than processed foods like soft drinks and candies. However, higher relative inflation for fresh fruits and vegetables was not entirely due to large upswings in commodity prices; changes in how produce is purchased in the grocery store also contributed. Whereas in 1985 consumers purchased heads of lettuce, today’s consumers are more likely to grab a bagged salad mix—complete with croutons and dressing. Loose whole fruits now share the produce aisle with containers of cut up fresh fruits and fruit salads. In addition to convenience, consumers’ preferences for healthier foods have driven demand for larger quantities and more year-round variety of fruits and vegetables.

Over the same time period, real prices for fats and oils, sugar and sweets, and nonalcoholic beverages grew less than overall inflation. A main ingredient in many nonalcoholic beverages is corn sweeteners, which have decreased in price nearly 20 percent since 1985. Processed foods are less affected by commodity-level price swings because commodity costs make up a smaller portion of processed foods’ retail prices. Instead, prices of processed foods are generally more closely linked to the costs of inputs such as electricity and wages; industrial electricity costs and manufacturing wages both increased at a rate about 10 percent lower than overall inflation.

The mix of inputs used in food products, and how the cost of these inputs change over time, affects the relative inflation rates for different types of foods. Higher relative inflation for fresh fruits and vegetables over the last 30 years partially reflects the produce industry’s response to consumer demand for more convenience and year-round variety in the produce aisle.

*On July 20, 2015, the third sentence of the article was revised to correct transposed values for eggs and red meats.

This article is drawn from:

- Food Price Outlook. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.