India Continues To Grapple With Food Insecurity

- by Sharad Tandon and Maurice Landes

- 2/3/2014

Highlights

- Despite progress, and large outlays on food subsidies, India continues to account for the largest share of the world’s food-insecure population.

- While most measures do indicate a large food-insecure population, accurate measurement of levels and trends in food insecurity is a significant problem faced by policymakers and is a major impediment to analyzing how food subsidies affect food and nutrition security.

- The newly enacted National Food Security Act will dramatically increase the number of households eligible for subsidized food grains under the current domestic food aid program. However, a number of questions remain regarding the immediate impact the legislation will have on food and nutrition security given the historically poor functioning of food aid in a number of Indian states and the difficulty in assessing changes in nutritional status.

Despite a nearly 20-year period of strong economic growth since the early 1990s, as well as the recent emergence of exportable surpluses of food staples—wheat and rice—India continues to account for the largest share of world population considered to be food insecure. Food security is defined as allowing individuals to reach a nutritional target of 2,100 calories per capita per day. USDA’s International Food Security Assessment, 2013-23 estimates India’s food-insecure population at 255 million, or about 36.1 percent of the 707 million food-insecure people among the 76 low-income countries studied. By the Government of India’s own count using a measure of poverty based primarily on the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet, 355 million Indians, or 29.8 percent of the population, lived in poverty in 2009/10.

The Indian government spends a significant share of its gross domestic product (GDP) on subsidized food grains and other essential commodities for poor households because of the persistently high level of food insecurity. Recent estimates suggest that the government spent nearly 1 percent of its GDP on its aid program in the past year, making it one of the largest domestic food aid programs in the world. Despite these large outlays supporting food-insecure households, a lack of progress in combating malnourishment has spurred the government to pass the National Food Security Act (NFSA), which will expand the coverage of India’s current food aid program and shift the program from a discretionary component of the social safety net to a legal right.

Recent ERS research raises questions about the measurement of food insecurity in India, the effectiveness of existing food distribution policies, and the potential effects of the recently enacted NFSA. One important question concerns the difficulties in accurately counting the food-insecure population and tracking changes in that population over time. Another concerns the historically poor functioning of India’s food aid program, known as the Public Distribution System, in delivering food to low-income households. Both issues complicate efforts by researchers and policymakers to evaluate the implications of planned reforms. However, recent improvements in the delivery of food aid in some Indian states, along with a sustained political commitment to tackle the problems of the existing food aid program, suggest that delivery of subsidized food grains to target groups has the potential to be a more effective tool to combat food insecurity.

Problems in Measuring Food Insecurity

There is no consensus estimate of the actual size of the food-insecure population in India or how it has changed over time; however, there is general agreement that the food-insecure population remains large. A variety of methods are used to assess the size of India’s food-insecure population. The method used in the ERS International Food Security Assessment and FAO’s The State of Food Insecurity in the World involves computing average calorie consumption from aggregate food supply and use balances. This approach facilitates comparison of food security estimates across countries. ERS researchers have also estimated calorie consumption using detailed household consumer expenditure surveys. Household level information is often more useful in the development and monitoring of food assistance programs.

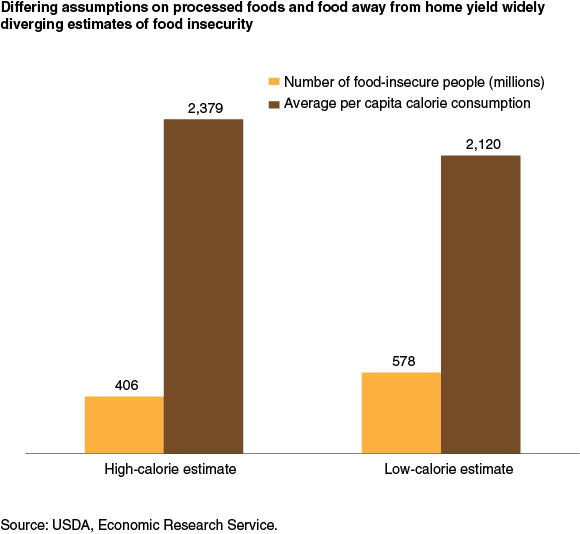

The various methods often yield widely differing estimates. Recent ERS research demonstrates that estimates derived from the household consumer expenditure survey data can differ significantly with relatively small changes in assumptions. ERS researchers recently used data from a large household expenditure survey data collected by the Indian government to estimate household-level calorie consumption. They found that estimates of the food-insecure population are particularly sensitive to assumptions regarding the calorie content of processed foods and food eaten outside of the household, neither of which can be directly computed from the survey data.

Researchers estimated average per capita caloric consumption using two equally plausible sets of assumptions to compute the calorie content of processed and unprocessed foods eaten both at home and away from home. To estimate calories consumed from processed foods, researchers calculated the price of non-processed calories and then assumed that processed calories are slightly more expensive. To estimate calories consumed in meals outside of the home, researchers estimated the decrease in at-home calories consumed in response to each additional meal consumed outside the home. Given the uncertainty in both estimation procedures, researchers experimented with different price premiums between processed and non-processed calories, as well as a range of estimates of calories consumed in meals outside the home.

The differences in consumption between the scenarios are striking. The high and low estimates made under the alternative assumptions differed by 259 daily calories per person. The different assumptions led to a 173-million-person difference between the high and low estimates of India’s food-insecure population in 2005—a difference equivalent to about 14 percent of the global food-insecure population estimated by USDA for that year.

There are two key findings from these estimates. First, both the high- and low-calorie estimates indicate that India has a large food-insecure population. Even the best-case scenario suggests nearly 40 percent of India’s population is food insecure. Second, the lack of precision in the estimates creates significant uncertainty in the number of food-insecure people. Because both consumption of processed foods and food away from home have been increasing over the past two decades, it is difficult to assess with certainty the extent to which food security conditions are changing over time.

Uncertainty in Food Security Makes Assessing the Efficacy of India’s Food Aid Program Difficult

Given the difficulty in assessing whether food security is improving or worsening over time, assessing the impacts of improvements in India’s food aid program on persistent malnutrition in the country is very difficult. India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) was established in the 1960s to provide subsidized distribution of a number of essential commodities— primarily food grains, sugar, and kerosene (used for cooking)—to households across India. Prior to 1997, the program was available to almost all households and was intended to stabilize food prices and provide food security by ensuring supplies of subsidized food staples. In 1997, the PDS was transformed into the Targeted Public Distribution System, which emphasized improved direction of food subsidies towards the poorest households.

The PDS is run by both central and state governments. The central government procures rice and wheat through the Food Corporation of India (FCI), which pays a government-mandated Minimum Support Price (MSP) to farmers. The central government then sells food grains at a lower price to individual states based on the number of households that are below the poverty line (BPL), which is based on the official poverty line set by the Planning Commission. States can also secure food grains for households above the poverty line (APL), but at a higher price. After receiving the food grains, state governments are responsible for identifying households and distributing commodities through a network of Fair Price Shops (FPSs).

Under the PDS, state governments identify below-poverty-line households eligible to purchase food grains at heavily subsidized prices. Above-poverty-line households are eligible to purchase food grains at an unsubsidized price equal to the government’s cost of procuring, storing, and delivering the grain. The DPS also targets the “poorest of the poor” with more steeply subsidized food grains, as well as supplies subsidized grains for school lunches and other welfare programs. The government also periodically releases grain from government stocks through Open Market Sales aimed at either regulating open market prices or reducing stock surpluses.

The cost of India’s food subsidy policy has increased significantly since 2000, reaching about $13.5 billion annually in 2011/12. The rising cost has been driven by higher support prices to farmers, unchanged issue prices for grain distributed through the PDS, and the cost of storing accumulated stocks. Per capita wheat and rice consumption has changed little, although PDS grain now accounts for a larger share of consumption, potentially increasing the ability of recipients to buy other foods. Assessments of the PDS indicate substantial leakages in the delivery of grains that prevent many households from purchasing their full ration. Estimates of diversion—the difference in the amount of PDS rations received by states and the amount households reported that they consumed—are high, some as high as 41 percent (Dreze and Khera 2010).

The imprecision noted in the methods used to measure food security makes it difficult to measure the effect of the DPS on food security. The calorie content for PDS food grains is relatively easy to measure, but it is possible that households use the substantial subsidy for food grains to substitute consumption towards processed foods and food away from home, which are both very difficult to measure. Alternatively, households can also use the food grains subsidy to increase consumption of non-food goods or food items with little nutritional value.

The National Food Security Act

The National Food Security Act (NFSA), signed into law in September 2013, will expand the share of households eligible for the most preferential subsidized prices and implement a number of safeguards to improve the distribution of food grains. Under the NFSA, the share of households eligible for subsidized grains increases to almost two-thirds of the country's population of 1.2 billion, although the allotment for the majority of recipients will be smaller than that for current BPL recipients. There is significant uncertainty over the form the transfers will take, as states are allowed to choose to distribute a food security allowance in lieu of in-kind subsidies. Magnifying this uncertainty, funds spent on procuring PDS food grains are considered agricultural support and are complicating the Doha Round negotiations of the World Trade Organization.

The NFSA makes access to subsidized food grains by qualified recipients a legal right supported by a dedicated grievance system, as opposed to a discretionary piece of the social safety net. Additionally, the NFSA also recommends that states implement other reforms to improve the present system. These include the designation of women as the recipients of subsidized grain within the household, preferences for public bodies and women's collectives in administering FPSs, doorstep delivery of food grains, public availability and computerization of records, periodic social audits, and vigilance committees from the state to the Fair Price Shop level to supervise the distribution process.

| Reform | Implication |

|---|---|

| Changes to Entitlements | |

| Establish legal right to subsidized food grains | Provide significant legal recourse for households in cases where food grains are not received by beneficiaries. |

| Expand coverage and reduce prices | Provide 5kg of subsidized food grains at the most preferential price currently in effect to 75 percent of the rural population and 50 percent of the urban population. States are to determine eligibility of households. Additionally, extra rations are provided to children, and women who are pregnant or lactating. |

| Reforms to Improve the Distribution of Food Grains | |

| Reform | Implication |

| Institute a grievance system | Allows households to file complaints against improperly run Fair Price Shops in the hopes of reducing diversion. |

| Auditing mechanisms | Computerization of records, delivery of food grains to Fair Price Shops (as opposed to having to pick up from the state storage facilities), changing management of Fair Price Shops away from private parties, etc. |

| Changes in ration card issuance | Ration cards given to eldest woman of the household over age 18. |

| Source: National Food Security Bill 2011, Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. | |

Many of these reforms mirror auditing mechanisms that have already been implemented by some state governments seeking to improve the distribution of PDS food grains. A number of states have taken steps to reduce the price of PDS food grains and expand access to the highest subsidies beyond the central government allotment, using their own funds to cover the additional costs (Khera, 2011). Several states have also introduced auditing mechanisms that better track and announce the delivery of food grains and also created mechanisms for households to file grievances with the system.

The states implementing these reforms had the political will and desire to improve the PDS. State governments finding that it is in their interest to have a better functioning PDS are more likely to pursue a number of unobservable ways to improve the efficacy of existing regulations. Unfortunately, predicting the efficacy of the reforms outlined in the NFSA in states where the PDS does not operate well and that lack the independent will to improve the distribution of subsidized food grains is not possible.

Additionally, in a few states where the PDS operates well, the list of beneficiaries is already more inclusive than the provisions of the NFSA, and there will be little additional effect on food security. Alternatively, other states have implemented reforms that are not included in the NFSA, and a number of reforms outlined in the NFSA have not been implemented elsewhere in India. Thus, the overall effects of the NFSA on the efficacy of distributing food grains, as well as food security, are difficult to predict.

What Does This All Mean for Food Security?

Whether implementation of the NFSA will be a durable answer to India’s large and persistent food security problem remains unclear. Although the current government is making a concerted effort to roll out the new NFSA provisions quickly, full implementation is likely to take time. National elections due in the first half of 2014 may also have implications for both the extent and pace of the new policy’s implementation. Given that the NFSA will have much smaller impacts in states where the list of PDS beneficiaries is more inclusive than the NFSA, along with a large amount of uncertainty regarding the distribution of food grains in states where the PDS operates poorly, the NFSA might have less of an immediate effect than expected by such a dramatic policy change.

Even if the provision of subsidized grains increases under the NFSA, the impact of subsidies on diet choice and food security is uncertain. Anticipating how households will spend the savings from food grains is difficult. Households might spend more on food away from home and processed foods where the nutritional content is essentially unobservable, or they might spend the savings on more nutritious foods, or alternatively on non-food goods or food items with poor nutritional content. Thus, the resulting effect on food security and nutrition could be difficult to infer.

Despite the difficulties of predicting the effects of the NFSA, improvements in a number of states in distributing PDS food grains demonstrate that an effective food aid program can be an integral component to combating food insecurity and malnourishment. As states with poor delivery of subsidized food grains improve their performance, pushed in part by federal legislation and in part by national attention to the issue, millions of vulnerable households will be provided with an extra layer of income support, which can help reduce persistent levels of malnourishment.

This article is drawn from:

- Jha, S., Srinivasan, P.V. & Landes, M. (2007). Indian Wheat and Rice Sector Policies and the Implications of Reform. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-41.

- Tandon, S. & Landes, M. (2012). Estimating the Range of Food-Insecure Households in India. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-133.

- The Sensitivity of Food Security in India to Alternate Estimation Strategies. (2011). Economic and Political Weekly XLVI (22), 92-99.