Disability Is an Important Risk Factor for Food Insecurity

- by Alisha Coleman-Jensen and Mark Nord

- 5/6/2013

Highlights

- One in three U.S. households that included an adult who was unable to work due to disability was food insecure in 2009-10.

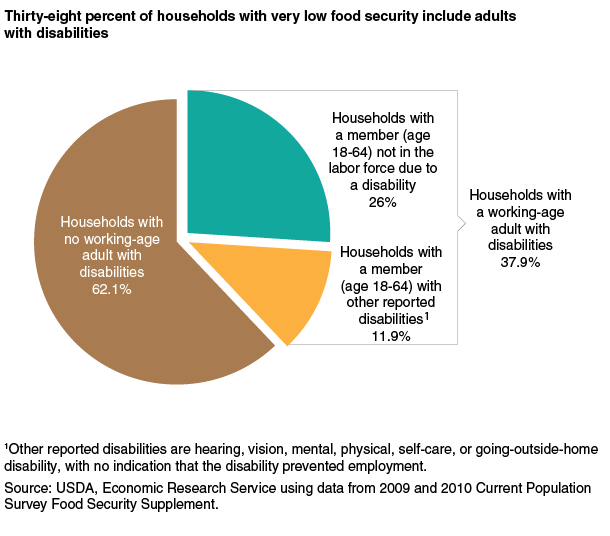

- An estimated 38 percent of households with very low food security included an adult with a disability.

- Substantially reducing the prevalence and severity of food insecurity in households that include adults with disabilities may help reduce the overall prevalence of food insecurity.

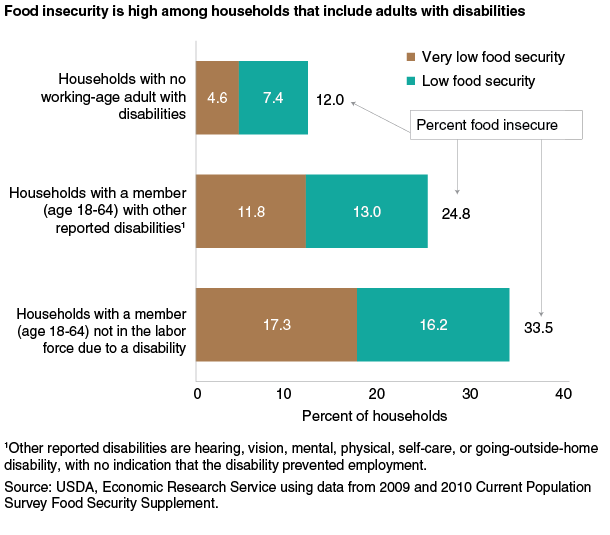

In 2011, close to 15 percent of U.S. households were food insecure. At some time during the year, these households lacked adequate food for one or more household members due to insufficient money or other resources for food. Disability has emerged as one of the strongest known factors that affect a household’s food security. Recent ERS research found that in 2009-10, one-third of households with a working-age adult who was unable to work due to disability were food insecure and one-quarter of households that included a working-age adult with a disability that did not necessarily prevent employment were food insecure. In comparison, 12 percent of households that had no working-age adults with disabilities were food insecure in 2009-10.

There is substantial overlap between households that include adults with disabilities and food-insecure households. Among factors known to correlate with food insecurity, only low income and participation in food and nutrition assistance programs identify such a large portion of the food-insecure population. It appears that current food and nutrition assistance programs and disability assistance programs designed to help people with disabilities meet their basic needs, including food security, are not fully compensating for the reduced earnings and higher costs associated with disability.

Reduced Earnings and Increased Expenses Put Households at Risk

Disability generally refers to a medical condition or health impairment that limits participation in usual roles or activities. In 2010, 21.3 percent of the U.S. population age 15 and older reported having a disability. ERS researchers used questions from the U.S. Census Bureau’s monthly Current Population Survey to identify two groups of households with working-age (ages 18-64) adults who have disabilities: those not in the labor force due to a disability and those with other reported disabilities that are not necessarily work limiting (see box, “What Types of Disabilities Are Identified?”). People with disabilities who are unable to work due to their disability may be more severely disabled or have poorer health than people whose disabilities are not keeping them out of the workforce.

Households that include people with disabilities may be particularly vulnerable to food insecurity. Disabilities often lead to reductions in earnings for the person with a disability and for other household members who may need to care for the individual with a disability. Monetary expenses related to health care, adaptive equipment, such as wheelchairs or special telephones, and other expenses associated with disability may result in an increased likelihood of food insecurity. Prior research has shown that people with disabilities require more income to meet basic needs than do persons without disabilities because they face higher expenses related to their disabilities. A study by Mathematica Policy Research found that a person with a persistent work-limiting disability would require more than two and half times the income of an able-bodied person to have the same likelihood of food insecurity. Individuals with disabilities may also have difficulty shopping for food, preparing healthy meals, and managing food resources.

Food insecurity, besides being more likely in households affected by disabilities, may also be more problematic for those households. A number of studies have shown that food insecurity has negative effects on health and diet quality, and these effects may be greater for people with disabilities. Disabling or chronic health conditions may be exacerbated by insufficient food or a low-quality diet.

Food Insecurity Is More Severe in Households That Include Adults With Disabilities

Not only is food insecurity more common among households affected by disabilities, but it also tends to be more severe in these households. That is to say, food-insecure households that include working-age adults with disabilities have a higher prevalence of very low food security than other food-insecure households. Very low food security is the severe range of food insecurity characterized by disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake. All food-insecure households have reductions in the quality or variety of their diet, but households experiencing very low food security also have reductions in the quantity of food—one or more members is not getting enough to eat. About one-third of all food-insecure households in the U.S. are in the very low food security category. For food-insecure households that include adults with disabilities, about half are in the very low food security category.

In 2009-10, 17.3 percent of households with a member who was not in the labor force due to disability had very low food security. An estimated 11.8 percent of households with a working-age adult with other reported disabilities (non-work-preventing) had very low food security. In comparison, among households with no working-age adults with disabilities, 4.6 percent had very low food security.

Households affected by disabilities account for a large share of all food-insecure households and an even larger share of all households with very low food security. In 2009-10, over one-quarter (26 percent) of households with very low food security included an adult who was not in the labor force due to disability. An additional 11.9 percent of households with very low food security included an adult with other reported disabilities. Altogether, about 38 percent of households with very low food security included a working-age adult with a disability.

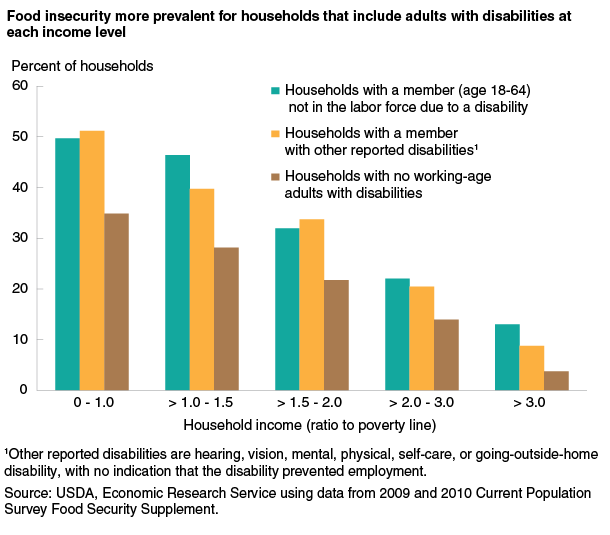

Food Insecurity High Even in Moderate-Income Households Affected by Disabilities

Disabilities may increase the likelihood of food insecurity due to increased household expenses as well as reduced earnings. Results from statistical models that account for the effects of employment, income, and other household characteristics show that reduced earnings and lower income among those with disabilities contribute to their high rates of food insecurity. However, even after adjusting for the effects of employment and income, the model results show that households with adults with disabilities are more likely to be food insecure than other households. Because they face higher expenses, households affected by disabilities require higher incomes to meet their basic needs than do households without members with disabilities.

Comparing rates of food insecurity across income categories provides a picture of the additional income households need to cover costs associated with disabilities. The prevalence of food insecurity for households with no working-age adults with disabilities is lower than or similar to that for households with a member not in the labor force due to disability in the next-higher income group.

Even households that have incomes greater than three times the poverty level have a relatively high likelihood of being food insecure if they include an adult with a disability. An estimated 13 percent of households that included an adult not in the labor force due to a disability and had incomes at least three times the Federal poverty line were food insecure. About 9 percent of households with a working-age adult with other reported disabilities and income at least three times the Federal poverty line were food insecure. In comparison, about 4 percent of households in that income range with no working-age adults with disabilities were food insecure.

Disability Assistance, Food Assistance, and Food Insecurity

Federal and local assistance programs are available to help individuals with disabilities meet their basic needs. These programs are meant to compensate for lower earning and higher expenses of those with disabilities. Many people with disabilities utilize these programs yet still have difficulty maintaining food security. The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program is available to low-income people with disabilities. Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is available to people with disabilities that have adequate work histories. Other disability assistance, such as workers’ compensation and veterans’ disability benefits, is also available. To be eligible for assistance, applicants must have a qualifying disability. Individuals with more severe disabilities are more likely to qualify for these programs.

Participation in disability assistance programs is relatively high among adults with disabilities, particularly those that are unable to work due to their disability. About 73 percent of households with a member not in the labor force due to disability received SSI, SSDI, or other disability assistance. Food insecurity was more prevalent among SSI recipients than among recipients of SSDI or other disability assistance. Higher rates of food insecurity among SSI recipient households may be due to more severe disabilities among those who qualify for SSI. It may also indicate that SSI benefits do not compensate for the lower income and higher expenses of more severe disabilities at a level that helps ensure household food security.

USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) includes special provisions for people with disabilities. In determining eligibility and benefit allotments, SNAP gives special consideration to those with a disability that receive government assistance for their disability. (For SNAP purposes, a person is defined as having a disability if he or she receives disability benefits such as SSI or SSDI.) One such provision allows households with members who have a disability to deduct medical expenses that exceed $35 per month from household income in determining SNAP eligibility and benefit allotments. This provision effectively increases the monthly SNAP benefit for those with disabilities and high medical expenses.

A larger percentage of low-income households that include adults with disabilities participate in SNAP than do low-income households without adults with disabilities. In 2009-10, an estimated 47 percent of low-income households with a member not in the labor force due to disability and 34 percent with a member with other reported disabilities received SNAP benefits, compared with about 24 percent of low-income households with no working-age adults with disabilities. Even though participation in SNAP was relatively high among households affected by disabilities, over half of these SNAP-recipient households were food insecure. This may be because households experiencing the worst food hardships are the most likely to apply for assistance. Also, the adjustments in SNAP benefits for people with disabilities may not fully compensate for the extra costs associated with disabilities.

Improving Food Security for Those With Disabilities

This research shows that disability assistance programs and food and nutrition assistance programs, in their current form, do not fully protect adults with disabilities from food insecurity. These individuals may benefit from closer program coordination and program revisions to improve their food security status. For example, future research may show that the special circumstances of individuals with disabilities require assistance beyond increased resources for food to meet their needs. People with disabilities may have difficulty managing food resources, getting to a store, and shopping and preparing healthy meals on their own, even if the size of their SNAP benefit is adequate.

Public and private food assistance programs tailored specifically to households with members who have disabilities may be necessary to substantially reduce their food insecurity. Given the large share of food-insecure households that include working-age adults with disabilities, improving the food security of those households would substantially reduce the overall prevalence and severity of food insecurity.

This article is drawn from:

- Coleman-Jensen, A. & Nord, M. (2013). Food Insecurity Among Households With Working-Age Adults With Disabilities. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-144.

You may also like:

- Food Security in the U.S.. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Coleman-Jensen, A., Nord, M., Andrews, M. & Carlson, S. (2012). Household Food Security in the United States in 2011. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-141.