Analysis of Those Leaving USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reveals the Program’s Effectiveness

- by Mark Nord

- 2/21/2013

USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest U.S. food assistance program, serving 46.6 million people monthly in fiscal year 2012. By providing eligible households with benefits to purchase food, SNAP stretches a family’s food budget and increases its food security, defined as consistent access to adequate food for active, healthy living. A recent ERS analysis suggests that SNAP reduces the number of recipient households with very low food security by about 38 percent, and the reduction may be as high as 59 percent for households that depend heavily on SNAP for their food purchases.

Earlier research had shown that SNAP improves the food security of participating households, but uncertainty remained as to the extent of that improvement. This stems from the fact that the most food-needy households--those with less money or other resources for food or those more concerned about the quality or adequacy of their diets--are more likely to sign up for the program than other eligible households. This “self-selection” effect more than offsets the beneficial effect of the program, with the result that simple comparisons of current SNAP recipients with nonrecipients generally find that SNAP recipients have worse food security than nonrecipients with similar incomes.

Adjusting statistically for differences in income, employment, and other characteristics typically measured in surveys only partially corrects for the effect of self-selection. Some of the important characteristics that determine both program participation and food security--income and employment volatility, asset holdings, food prices, recurring nonfood expenses, and general aversion to acceptingassistance--are not readily measured in surveys and, therefore, are difficult to account for when analyzing the program’s impact.

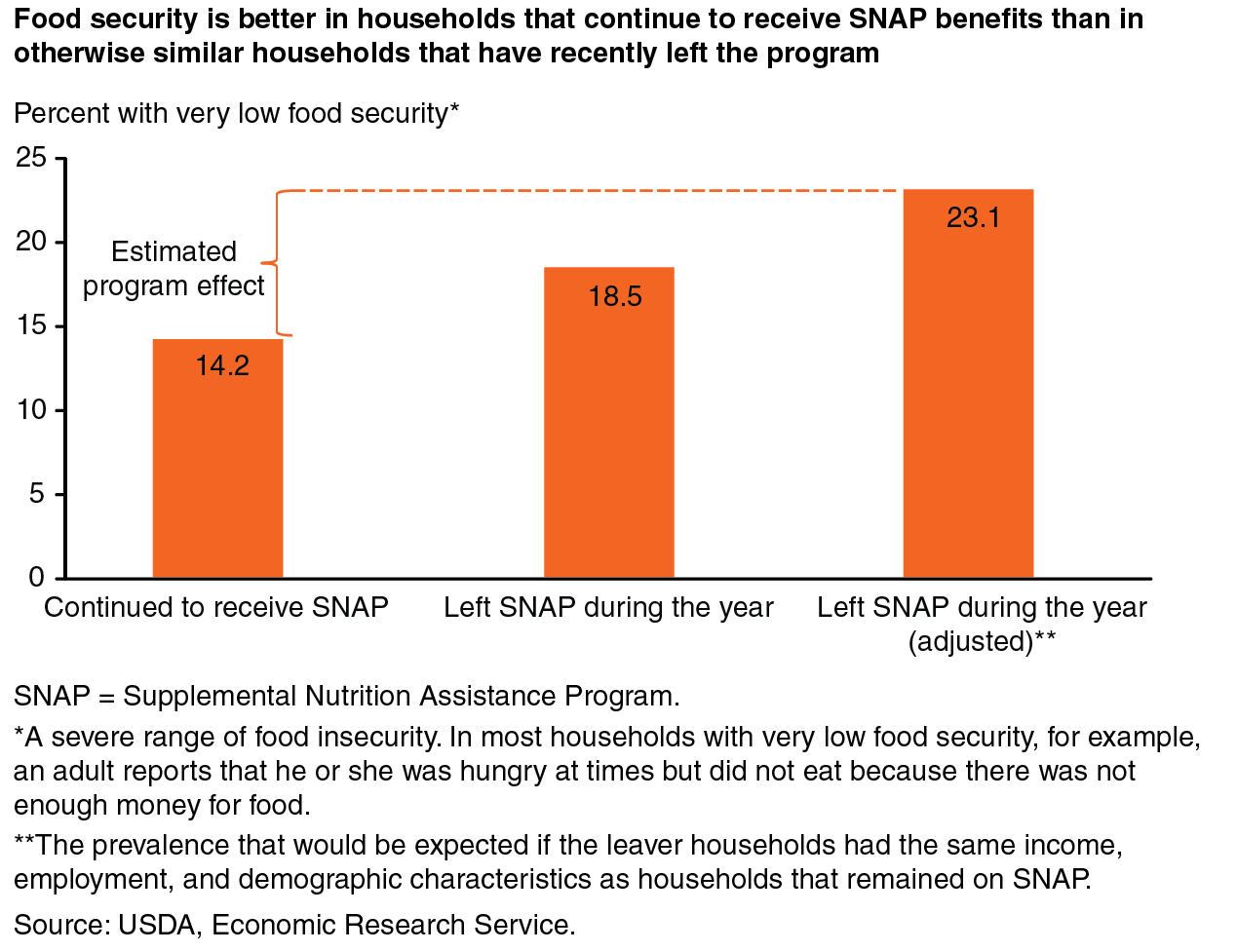

A recent ERS analysis sought to overcome the self-selection effect by comparing the food security status of current SNAP recipients with that of households that had recently left the program. This approach removes much of the self-selection effect because it inherently adjusts for unobserved characteristics that do not change at the time households leave the program. The difference of 8.9percentage points in prevalence of very low food security between households that continued to receive SNAP benefits (14.2 percent) and households that had recently left the program (23.1 percent, after adjusting for their higher incomes and other more favorable conditions) provides an estimate of SNAP’s effectiveness in improving the food security of participating households.

This article is drawn from:

- How Much Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Alleviate Food Insecurity? Evidence From Recent Programme Leavers. (2012). Public Health Nutrition. Vol. 15, No. 5, 2012, pp. 811-817.