Dietary Guidelines Have Encouraged Some Americans To Purchase More Whole-Grain Bread

- by Lisa Mancino and Fred Kuchler

- 12/3/2012

Since its inception in 1980, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans have provided consumers with science-based nutritional principles and advice for making healthy food choices. So far, there is little evidence that Americans' overall diet quality has improved in response to updated Dietary Guidelines issued every 5 years. However, a recent study by ERS finds that, for whole grains, the 2005 Guidelines were able to nudge consumption patterns in the direction desired by the public health community--at least for some consumers.

The 2005 Guidelines recommended that half of all grains consumed be whole grains. A comparison of grocery store bread purchases before and after the release of the 2005 Guidelines shows that the quantity of whole-grain bread purchased rose nearly 70 percent, while refined-grain bread purchases fell 13 percent. Of course, these purchase shifts cannot be fully attributed to the Dietary Guidelines. While overall bread prices were rising over this period, whole-grain bread prices relative to refined-grain bread prices were falling.

Demand analysis by ERS, which separated the impact of the Dietary Guidelines from other economic factors affecting purchase decisions, shows that falling relative prices of whole-grain bread accounted for much of the shift toward whole-grain bread purchases. Nonetheless, after accounting for relative prices, changing consumer incomes, seasonality in bread demand, and regional differences in food preferences, there are additional changes in purchasing behavior that can reasonably be attributed to the Dietary Guidelines. The 2005 Guidelines appear to have encouraged Americans to reduce purchases of refined-grain breads by 3 percent and increase purchases of whole grain bread by 14 percent.

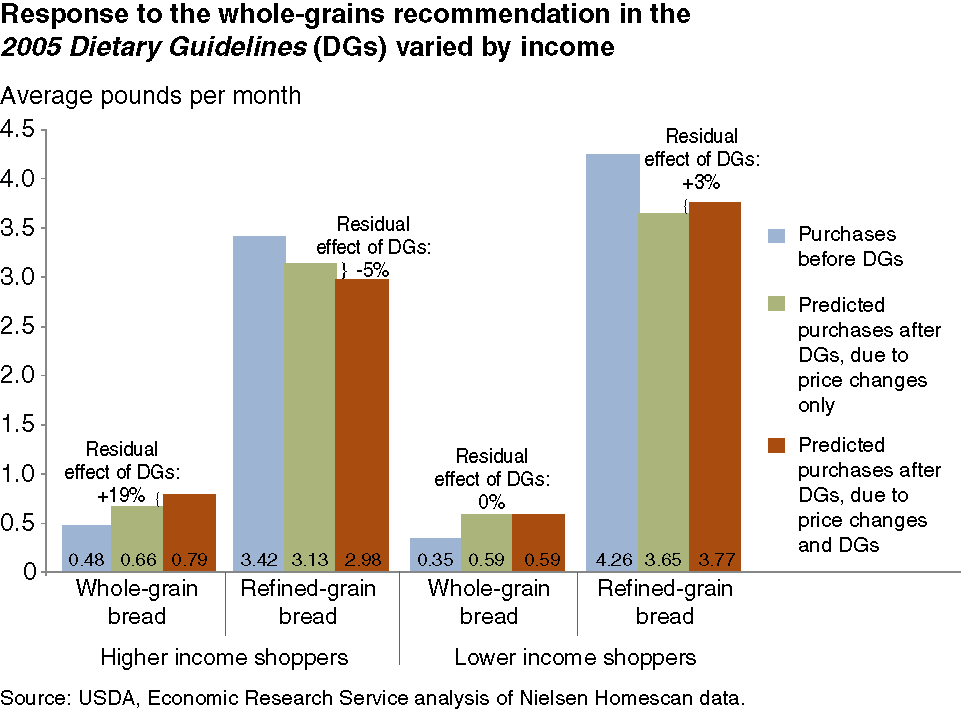

After accounting for price effects and other factors influencing demand, ERS finds that the 2005 Guidelines were responsible for households with incomes above 185 percent of the Federal poverty level increasing their whole-grain bread purchases by 19 percent (from 0.66 to 0.79 pounds per month) and decreasing refined-grain purchases by 5 percent (from 3.13 to 2.98 pounds per month). When looking at lower income households, there was no evidence that the Dietary Guidelines provided much of a nudge. While lower income households also increased their purchases of whole-grain bread, this was found to be almost entirely due to declining relative prices of whole-grain bread.

The 2005 whole-grain recommendation may owe its positive impact to a couple factors. The advice on healthy substitutes was specific and relatively easy to follow--buying a loaf of whole-grain bread is very much like buying a loaf of refined-grain bread. At the same time, the 2005 Dietary Guidelines may have provided manufacturers with incentives to reformulate their products in anticipation of increased demand for whole-grain products, and this may have created a spillover benefit. When manufacturers ramped up their whole-grain production, they likely created some scale economies, lowering per unit production costs and thereby lowering the relative price of whole-grain bread for all consumers.

This article is drawn from:

- 'Demand for Whole-Grain Bread Before and After the Release of the Dietary Guidelines'. (2012). Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. Spring, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 76-101..