Amber Waves in the Fertile Crescent: The Changing U.S. Role in Agricultural Markets in the Middle East and North Africa

Highlights:

-

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region accounts for a large and growing portion of the world’s import demand for several important agricultural commodities.

-

The MENA region’s demand for more calories and a more diversified diet is driven by its growing populations and rising incomes, two trends that translate into rising demand for food imports.

-

Some U.S. agricultural exports to the MENA have dropped due to rising competition from other countries, domestic demand for corn-based biofuels, and recent high commodity prices in global markets.

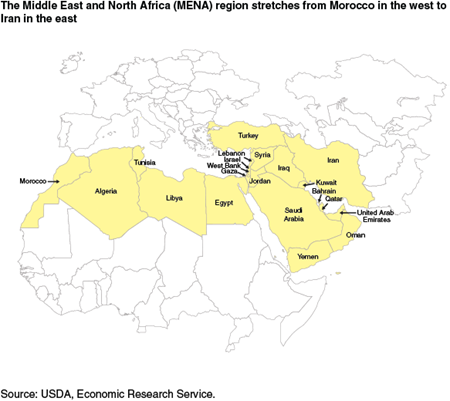

Home to history’s earliest agricultural producers, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region today does not produce enough food to feed its rapidly growing population. Facing production constraints imposed by its mostly arid climate and desert soils, the MENA has increasingly relied on the outside world to supply it with crop and meat commodities for food.

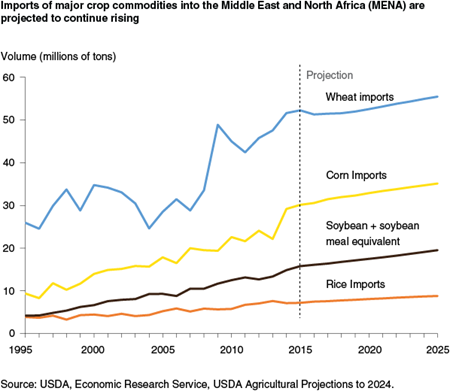

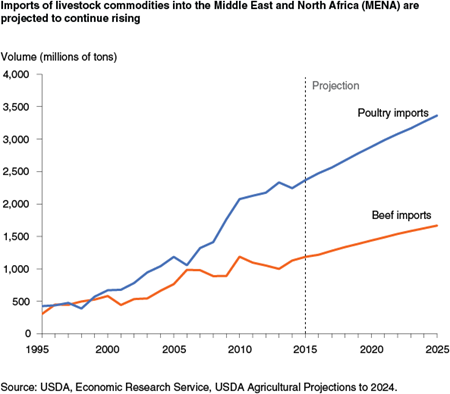

The MENA region’s rising food imports are projected to account for a sizeable portion of future growth in world agricultural trade. MENA’s shares of growth in total world imports of corn and wheat are 23 percent and 44 percent, respectively, and for poultry and beef, the shares are 31 percent and 30 percent, respectively. For these commodities and many others, MENA represents an increasingly important market for agricultural exporters, including the United States.

Historically, the United States has played an important role in meeting the MENA region’s food needs. But recently, U.S. grain exports to the region have declined due to new, competing suppliers from Latin America, Eastern Europe, and South Asia. Rising domestic demand for biofuel feedstock, particularly prior to 2010, further diverted U.S. grains away from export markets. Against this landscape of changing demographics, markets, and policies, U.S. agricultural shipments to the MENA have evolved in size and composition.

What’s happening in MENA today?

Like many developing and emerging economies, the MENA region is experiencing population and income growth. Home to nearly 500 million inhabitants—the most populous countries are Egypt, Turkey, and Iran—MENA’s population is growing faster than almost anywhere else in the world. Similarly, incomes are generally growing, but this masks considerable variability across the countries of the region. Incomes in the wealthy, oil-rich states of the Persian Gulf contrast starkly with resource-scarce countries such as Egypt, Morocco, and Yemen, where a sizeable fraction of the population lives in poverty. MENA’s income and population growth rates are projected to exceed the world’s growth rates over the next 10 years.

Against this backdrop of population growth and mixed economic performance, recent political instability in some parts of MENA, coupled with rising and volatile international agricultural commodity prices, have caused the region’s food imports to fluctuate and left some governments struggling to subsidize basic food staples. These developments have not only complicated the trade landscape, but also potentially jeopardized the food security of the region’s poorest consumers.

Food and agriculture in the MENA

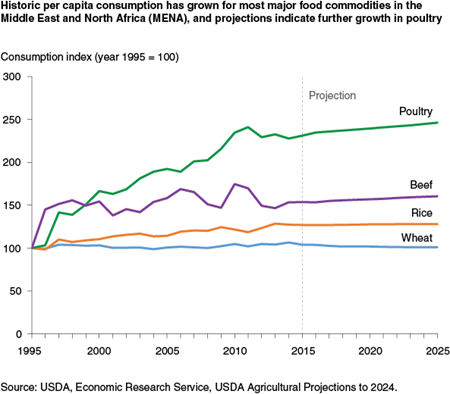

Like many parts of the developing world, growing populations and incomes in the MENA region have rapidly driven urbanization and the emergence of a middle class, leading to rising demand for food and evolving preferences for different and new foods. Over the past 50 years, calorie consumption has risen substantially, but the percentage of those calories coming from cereal grains has fallen while calories from meat have more than doubled. Wheat and rice consumption have remained flat while poultry and beef have grown. The trend towards rising meat and dairy product consumption is a common occurrence in developing and emerging economies.

At the same time, the MENA region’s ability to produce the crops and livestock needed to meet that demand is limited by its geography and climate. Across most of North Africa and stretching into the Arabian Peninsula, vast deserts cover the land, with small arable pockets concentrated in the same areas that comprised the original Fertile Crescent. Average rainfall levels for the region are not only among the world’s lowest but also highly variable, contributing to low yields that rise and fall unpredictably in areas such as Morocco. The main exception is Egypt, where irrigated production leads to high yields, but limited arable lands keep overall production low.

Whether due to low yields or limited arable lands, countries in MENA consequently rely heavily on imports to satisfy their food demands. MENA imports account for a large share of globally traded food commodities. The United States shipped about $10 billion worth of agricultural goods to the MENA region annually in 2011-13, accounting for about 7 percent of its total agricultural exports. The most important U.S. grown commodities exported to the MENA region are tree nuts, grains and feeds, and horticultural products. Major destinations include Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Morocco, and Tunisia.

Profile of U.S. agricultural exports to the MENA

While the MENA region’s import demand for crop commodities has steadily grown, the role of U.S. exports in satisfying this demand has been mixed. U.S. shipments of wheat and corn have fallen since the early 2000s. Soy products have grown sporadically over the same period, while U.S. rice and cotton exports have remained steady. In contrast to the crops picture, however, U.S. meat exports, particularly poultry, have grown consistently over the past 10 to 15 years.

A number of factors lie behind recent fluctuations in U.S. exports to MENA. Brazil and Argentina’s entry into world soybean markets has put significant price pressure on U.S. soybean shipments worldwide. Meanwhile, large-scale wheat and corn producers in Eastern Europe and Russian are taking advantage of their proximity to MENA buyers to compete for market share. Closer to home, the domestic biofuels boom, as well as growing worldwide demand for feed grains, has led some U.S. farmers to shift more land to corn, dampening wheat production and reducing supplies for export. Meanwhile in rice markets, the global food commodity price crises in 2007-08 and 2010-11 saw major rice-consuming (and producing) nations impose restrictive measures on rice exports. In response, not only did world rice prices jump even higher, but major importers, including several countries in the MENA, sought out new suppliers for the short term, presenting opportunities for U.S. rice exports to grow.

Projections for MENA’s imports of major crop and livestock commodities suggest that the crop commodities, particularly food grains, will grow at slower rates than in the past. In contrast, feed commodities, namely corn and soy products, are expected to continue their long-term historic rate of growth throughout the projection period. Similarly, beef and poultry products will experience continued strong growth.

Profiling the major U.S. export commodities to MENA

Wheat

In Egypt, the Arabic word “aysh,” meaning life, is commonly used in reference to bread, equivalence underscoring the importance of bread as a staple food throughout the MENA region. As its main ingredient, wheat represents the most important commodity consumed in the region, accounting for about 35 percent of the caloric intake for the average MENA inhabitant. While MENA diets have gradually diversified thanks largely to rising incomes, governments throughout the region continue to subsidize both wheat producers and bread consumers. These subsidies, along with a growing population, have sustained MENA’s wheat demand.

Despite the importance of wheat in the MENA diet, wheat cultivation in the region is limited by the region’s geography and climate. Most production in the region is rain-fed, and with highly variable annual rainfall levels, particularly in Morocco and Turkey, yield levels and overall production levels can fluctuate significantly.

Given these conditions, wheat consumption often exceeds production by over 80 percent, and thus, the MENA relies heavily on imports to meet its needs. Historically, much of this supply originated in the United States, but U.S. exports have gradually fallen over the past 20 years, due primarily to the gradual shift among U.S. producers towards more profitable corn and soybean rotations. Simultaneously, increased imports from wheat growers in Black Sea countries as well as the European Union have pushed the U.S. share of MENA’s total imports down to around 10 percent.

Egypt, with the region’s largest population, is the largest wheat importer, accounting for slightly more than half of all U.S. exports to the region, though year-to-year volumes have fluctuated. Other important buyers include Turkey, Algeria, Israel, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia, where recent policies have de-emphasized domestic wheat production and created opportunities for American producers.

Rice

Rice is another important cereal grain in the MENA diet. Major rice producers in the region include Egypt, Turkey, and Iran, but as with other crops, production lags far behind consumption and is not expected to rise appreciably due to climate and land constraints. The MENA consumed an average of 13 million tons of rice annually over the period 2011-13, of which around 7 million tons were imported. The U.S. share of the MENA import market has hovered around 10 percent, as emerging competitors in South Asia and Thailand have gradually made inroads due to lower prices and closer geographic and cultural proximity.

Turkey, Libya, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia are major buyers of U.S. rice. Some of these markets emerged in the wake of the recent food price crisis when the usual suppliers, namely Egypt and India, imposed export bans. While trade policies remain unpredictable, rising incomes and populations in the region remain certain and are expected to sustain rice demand going forward, leaving the door open for a growing U.S. role in this market.

Corn

Used primarily as livestock feed, corn is cultivated primarily in Turkey, Egypt, and Iran. While most production is irrigated, corn remains subject to the same climate and geography constraints that limit wheat production, leaving relatively little room for growth. MENA corn consumption has grown steadily over the past 20 years, primarily owing to growing poultry production. As the capacity for large-scale poultry operations has grown, so has the demand for animal feed, for which corn is a main ingredient. Again, rising incomes are driving demand for poultry and meats, but whether this translates into more demand for imported feed for domestically produced poultry or imported poultry itself will likely vary within the region.

While total corn imports into the MENA have steadily risen, the U.S. share of imports into the region have declined from about 70 percent during the mid-1990s to around 10 percent in recent years, partially due to U.S. biofuels markets as well growing competition from South America, Ukraine, and Russia, all of which enjoy transport cost advantages to the MENA region. Meanwhile, China remains a large variable, where sudden changes in demand can immediately divert corn shipments away from traditional markets. As with other commodities, rising incomes and growing populations mean that MENA’s corn demand will continue to grow and likely sustain future shipments of U.S.-grown corn. Major buyers of U.S. corn include Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

Soy products

Despite recent years of volatility, MENA soy products consumption has risen over the past 20 years, almost entirely due to rising demand for poultry and other meat products. Demand for soybean and soymeal imports varies across the region, depending on each country’s domestic crushing capacity. Egypt’s government-protected domestic crushing capacity orients the country’s import demand towards soybeans, while other markets in the region purchase U.S. soymeal.

U.S. shipments of soybeans to MENA have been variable, but have trended upward over the past 10 years, generally tracking consumption. Major destinations for U.S. soy products include Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, and Israel. The U.S. share of the MENA import market has recently declined as price-competitive producers Brazil and Argentina have claimed a greater portion of this expanding market.

Poultry

MENA poultry production has grown rapidly but has not kept pace with consumption growth, resulting in rising imports. In fact, MENA is the largest regional importer of poultry products in the world, and within the region, Saudi Arabia is the largest buyer. U.S. poultry shipments, mainly broilers, saw rapid growth over the past 10 years, with the biggest customers being Iraq and the United Arab Emirates.

U.S. poultry shipments to MENA have more than doubled over the past 10 years, reaching 364,000 million tons (mt) in 2013. Despite this growth, however, the U.S. share of the MENA import market has hovered around 15 percent, due mainly to the expansion of imports from other source countries. The largest competitor to the United States is Brazil, which has seen its world exports more than double over the past decade; Turkey has also emerged as a large local supplier to the MENA region.

Other products

Other commodities that figure prominently in U.S. exports to MENA include cotton, beef and veal, and tree nuts. U.S. cotton primarily supplies Turkey’s textile industry. Beef and veal shipments to the region have grown in recent years, but this sector has been dominated by producers in South Asia. Meanwhile, tree nuts, mainly almonds, were the second-highest value U.S. commodity shipped to the region, nearly surpassing wheat in 2012. The largest markets for this specialty crop originating in California are the United Arab Emirates and Turkey.

Conclusion

The Middle East and North Africa region’s population growth and rising incomes have pushed demand for agricultural commodities upward. This demand is expected to continue rising in the face of flat domestic production, despite uncertainties posed by trade policies and, increasingly, regional political instability. While emerging competition from South America, Eastern Europe, and South Asia have lowered the U.S. market share in MENA, the region’s growth is expected to continue lifting the demand for imports, affecting not only global commodity trade, but also the opportunities available to U.S. producers.

International Baseline Data, by Baseline Team, USDA, Economic Research Service, February 2024

Middle East and North Africa Region: An Important Driver of World Agricultural Trade, by Getachew Nigatu and Mesbah Motamed, USDA, Economic Research Service, July 2015

USDA Agricultural Projections to 2024, USDA, Economic Research Service, December 2022