Food Insecurity Rates Are Relatively High for Participants in Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Assistance Programs

Highlights:

-

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) served more than 4.5 million low-income U.S. households in 2019 via three programs that help families obtain affordable housing.

-

A recent USDA, Economic Research Service study found that the prevalence of food insecurity was relatively high for participants receiving Federal housing assistance: across the three HUD programs, 37 percent of adult participants were food insecure over a 30-day period in 2011-12—almost double the national rate for low-income households over a 30-day period.

-

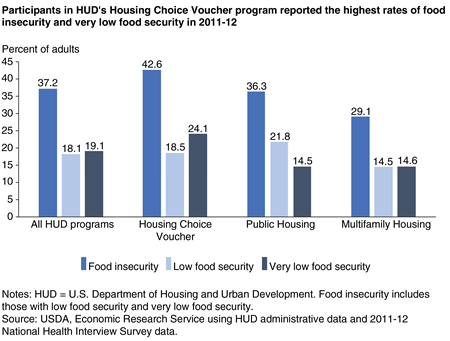

The prevalence of food insecurity varied across the HUD programs, with the highest rate occurring among households participating in the Housing Choice Voucher program.

Housing costs represent a significant expenditure for low-income families, with some research finding that more than half of low-income families with children spend more than 50 percent of their incomes on housing. For low-income households, the burden of high housing costs is a chronic issue that reduces housing stability and increases the risk of food insecurity, which is defined as the inability to provide all household members at all times with enough food for active, healthy lives. Housing assistance may be a resource that helps low-income families avoid food insecurity. Alternatively, families that qualify for housing assistance may have such limited resources that they risk food insecurity even when they receive housing assistance.

Public assistance programs, even those that do not explicitly target food insecurity, may improve a household’s food security by reducing the household’s overall financial burden. Two Federal agencies—USDA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—operate rental assistance programs that seek to reduce the housing-cost burden for low-income families. USDA operates multifamily housing programs in rural towns and small cities in all 50 States and outlying U.S. territories. Rental assistance helps keep participating families’ monthly rental bills to an amount that does not exceed 30 percent of income. In 2019, a total of 252,319 families received $1.3 billion in rental assistance from USDA (see box, “USDA Provides Housing Assistance in Rural Towns and Small Cities”).

HUD helped more than 4.5 million low-income U.S. households, mostly in urban areas, receive affordable housing in 2019 via three rental assistance programs: Public Housing, Multifamily Housing, and the Housing Choice Voucher program. However, because housing assistance is targeted to very low-income households, even with the assistance, many of these households were food insecure. A recent study, led by Economic Research Service (ERS) and HUD researchers, analyzed national administrative data for three of HUD’s largest programs and found that the prevalence of food insecurity varied across HUD programs, with the highest rate occurring among households participating in HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher program.

HUD Provides Low-Income Families With Rental Assistance Via Three Programs

Food insecurity is a serious public health concern affecting many low-income households in the United States. A food-insecure household is one that reports having times when, because of insufficient resources, it is unable to acquire adequate food for one or more household members. In 2019, an estimated 10.5 percent of U.S. households were food insecure at least once during the prior year; among households with incomes below the poverty threshold, the prevalence was 34.9 percent.

One factor that can drain a low-income household’s resources for food is competing costs, such as those for medical care, childcare, transportation, and housing. For example, if funds must go to cover childcare or transportation, less money is available to be spent on food. Medical bills and higher-than-expected increases in energy prices also can strain the food resources of low-income households. A 2017 ERS report found that unexpected hikes in energy prices increase the likelihood of a low-income household becoming food insecure.

Housing costs typically are among a household’s larger expenses. HUD defines low-income households that spend 50 percent or more of their income on housing costs as having a severe rent burden. In 2015, 8.2 million U.S. households had severe rent burdens. HUD’s three major rental assistance programs (Public Housing, Multifamily Housing, and the Housing Choice Voucher program) are each made up of several sub-programs and are generally designed to reduce housing-cost burden. These programs have similar eligibility criteria but differ in terms of subsidy type, payment standards, and methods of paying utility bills—factors that influence housing-cost burden and potentially contribute to food insecurity.

The Public Housing and Multifamily Housing programs subsidize specific affordable apartments or houses owned by local housing authorities (Public Housing) or private owners (Multifamily Housing). This type of assistance is often referred to as “project-based assistance,” because the subsidy is linked to a specific unit. In the Housing Choice Voucher program, participants lease housing of their own choosing from private owners who agree to participate in the program. In general, participants in the Housing Choice Voucher and Multifamily Housing programs contribute approximately 30 percent of their household incomes to rent. This is also true for Public Housing, but some tenants in this program have the option to pay a fixed rent (often set at $50 per month), which typically falls well below 30 percent of total household income. The HUD-provided subsidy pays the remaining rent amount up to a specified limit that varies by program.

Prior research shows that rent burden is generally lower for households receiving assistance through the Public Housing program than it is for households receiving assistance through the Housing Choice Voucher and the Multifamily Housing programs. Due to limited funding and resource availability, only 25 percent of eligible households receive housing assistance.

Prevalence of Food Insecurity Varies For the Three HUD Programs

Researchers from ERS and HUD linked National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2011 and 2012 to HUD administrative—or program—data to examine the relationship between household food insecurity and the three major HUD rental assistance programs. (The years 2011 and 2012 were the only years for which both linkable HUD administrative data and NHIS food security data were available at the time of the study.)

Food-insecure households were identified through a series of 10 questions in the NHIS about food-related conditions experienced by adults. In each of the questions, resource constraints were acknowledged as the reason for the food-insecure condition. Questions probed the severity of the problem, ranging from anxiety about the household food supply to going a whole day without eating. For example, one of the questions in the middle of that range is: “In the last 30 days, did you or other adults in your family ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn't enough money for food?” An NHIS participant who responded affirmatively (“often,” “sometimes,” or “yes”) to three or more questions was classified as living in a food-insecure household. Food-insecure households can be further separated by the severity of the food insecurity they experienced into either having “low food security” or the more severe “very low food security.” Food-insecure participants who affirmed three to five questions relating primarily to reduced dietary quality or variety were classified as experiencing low food security. Food-insecure participants who affirmed six or more questions, including reporting reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns such as skipped meals, were classified as experiencing very low food security.

Among adults participating in any of the three HUD programs at the time of their NHIS interview, 37.2 percent reported household food insecurity in the previous 30 days—18.1 percent had low food security and 19.1 percent had very low food security. The prevalence of low food security and very low food security sum to the prevalence of food insecurity. Prevalence of food insecurity varied by HUD program. In 2011-12, 42.6 percent of Housing Choice Voucher recipients, 36.3 percent of residents of Public Housing, and 29.1 percent of residents of Multifamily Housing reported being food insecure. Adults in the Housing Choice Voucher program reported a rate of very low food security (24.1 percent), which was almost 10 percentage points higher than rates found in the other two programs.

Several household-level characteristics were associated with food insecurity among HUD participants: poverty level, the presence of an elderly person in the household, whether any family member reported fair or poor health, whether any family members were working in the week prior to the survey, and whether the family reported trouble paying medical bills in the past 12 months. For example, households without elderly adults were more likely to be food insecure than were households that included elderly members. This is consistent with national data that show the overall food insecurity rate for all households is higher than the food insecurity rate for elderly households. Elderly people may have pensions or Social Security payments that provide stable household income. Households with family members in fair or poor health and households having problems paying medical bills were more likely to be food insecure than were households that did not report those conditions.

Family type (number of adults and children) and the highest level of education attained by an adult in the household had a smaller but still significant association with food insecurity. For example, the presence of children was associated with somewhat lower household rates of food insecurity for all three programs than rates seen in households that include no children. This finding for the population of HUD-assisted households is different from what we find in the Nation overall, where households with children generally have higher food insecurity rates than those without children. This study could not explain why HUD-assisted households without children faced higher food insecurity rates.

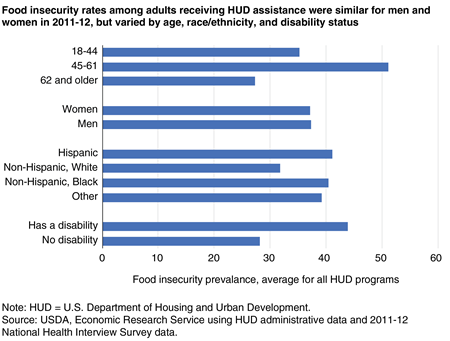

Looking at individual-level characteristics, the researchers found that age, race/ethnicity, and disability were associated with food insecurity, but gender was not. Among adults receiving HUD assistance, food insecurity was more prevalent for those 45 to 61 years of age and for those with a disability. This finding that adults with disabilities in HUD-assisted housing had higher food insecurity rates than those without disabilities is consistent with national food insecurity trends: Households that include adults with disabilities are more likely to be food-insecure than households that do not include adults with disabilities. The higher risk for food insecurity among those with disabilities holds even after controlling for differences in income and other characteristics.

Understanding Differences in the Likelihood of Food Insecurity Between HUD Programs

To identify whether differences in the characteristics of the people served by each HUD program explained differences in food insecurity rates between the programs, the researchers controlled for these individual- and household-level characteristics. After controlling for these characteristics, the researchers found that among adults in the Housing Choice Voucher program, the probability of residing in a food-insecure household was 41 percent, while among adults in the Public Housing and Multifamily Housing programs, the probability of living in a food-insecure household was 37 percent and 31 percent, respectively. These adjusted predicted probabilities are very similar to the uncontrolled prevalence rates. This suggests that differences in characteristics of households across the three HUD programs do not explain the variation in food insecurity rates among the programs.

Adults participating in the Housing Choice Voucher program may face higher rates of household food insecurity than demographically similar adults in the Public Housing and Multifamily Housing programs for a couple of reasons. First, participants in these two programs generally spend less of their household income on housing than do those in the Housing Choice Voucher program. Theoretically, Housing Choice Voucher tenants should not spend more than 30 percent of their household income on rent; in reality, Housing Choice Voucher tenants may experience housing cost burdens that exceed 30 percent of income. Spending more than 30 percent of income on rent is less likely in the other two programs.

Second, previous studies suggest that it can be difficult for families who pay rent and utility bills separately to manage overall finances and to adapt accordingly. While Multifamily Housing and Public Housing tenants typically pay one flat amount that covers rent and utilities, Housing Choice Voucher tenants must manage these bills separately. Financial management challenges associated with paying rent and utility bills separately could be another reason for higher rates of household food insecurity among Housing Choice Voucher tenants.

Differences in the likelihood of food insecurity across HUD programs could also stem from other factors, including whether the apartment or house is assigned (Public Housing and Multifamily Housing) or is independently selected by the household (Housing Choice Voucher), as well as differences in characteristics of the neighborhoods where a HUD program participant lives. The local food environment may also play a role. If, for example, a household receiving HUD assistance lives in a neighborhood lacking well-stocked, low-price grocery stores, its food security could be compromised.

While understanding how types of housing assistance may be linked with food insecurity is important, it is also important to note that food insecurity rates are relatively high for all three HUD programs. Linking HUD administrative data with other data sources has the potential to provide insight into the complex relationship between poverty, housing burden, and food insecurity.

USDA Provides Housing Assistance in Rural Towns and Small Cities

by John Cromartie

USDA’s Multifamily Housing programs provide direct loans, guaranteed loans, and grants for construction, repair, and renovation that currently maintain more than 13,500 rental properties in rural towns and small cities across the country. Two-thirds of the 385,579 households living in these properties also received USDA rental assistance in 2019, keeping their monthly bill to no more than 30 percent of their income. The average income of tenants receiving USDA rental assistance was $11,557 in 2019, less than one-fifth the national average. Rental assistance totaled $1.3 billion in 2019, just over $5,000 per household. More than one-third of properties are set aside for household heads 62 years old or older or persons with disabilities regardless of age. Elderly, disabled, and handicapped households make up 67 percent of households receiving USDA rental assistance.

When the USDA loans to the owners of these rental properties reach their final payment, tenants no longer qualify for rental assistance. Most USDA multifamily rental properties were built before 1990 and many of these properties need refinancing to keep them in the program. USDA efforts are now directed primarily to the rehabilitation and preservation of these older properties. For instance, the Multi-Family Rental Preservation and Revitalization program obligated 208 loans and grants totaling $131 million in 2019. USDA also funded 130 grants totaling $14.5 million through the Housing Preservation Grant program.

The statistics reported in the two paragraphs above come from:

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2019 Rural Development Multi-Family Housing Annual Occupancy Report. Washington, DC: USDA, December 5, 2019.

Housing Assistance Council, USDA Rural Development Housing Activity: Program Obligation Report Through September FY 2019. Washington, DC: Housing Assistance Council.

Household Food Insecurity and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Federal Housing Assistance, by Veronica E. Helms, Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Regina Gray, and Debra L. Brucker, ERS, November 2020

The Effects of Energy Price Shocks on Household Food Security in Low-Income Households, by Charlotte Tuttle and Timothy K. M. Beatty, ERS, July 2017

Household Food Security in the United States in 2019, by Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Matthew P. Rabbitt, Christian A. Gregory, and Anita Singh, ERS, September 2020

Food Insecurity Among Households With Working-Age Adults With Disabilities, by Alisha Coleman-Jensen and Mark Nord, USDA, Economic Research Service, January 2013