New Regulations Will Inform Consumers About Calories in Restaurant Foods

Highlights:

-

Menu-labeling regulations released by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration require chain restaurants to post the calorie content of menu items at the point of sale.

-

ERS research shows that consumers who already have healthier diets are more likely to use nutrition information provided by restaurants.

-

ERS research reveals that, although “rules of thumb” can help consumers identify large calorie differences, they are not much help when trying to distinguish between foods that differ by less than 200 calories.

Because of menu-labeling regulations developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), consumers across the country will soon be seeing calorie contents for foods, beverages, and meals when they eat out at larger chain restaurants. Fast-food restaurants must post the number of calories in burgers, sandwiches, and other foods on their menu boards; in full-service restaurants with wait staff, calories must be noted in the menus. For items that are self-service or on display for purchase, calories must be declared on signs adjacent to the foods. Restaurants have until December 1, 2015, to comply with these new regulations.

The underlying premise of the new regulations is that providing consumers with nutrition information will enable them to make informed and healthful dietary choices. ERS research shows that Americans typically make less healthy choices when eating out, including by consuming more calories. Two ERS studies in 2010 found that each away-from-home meal that replaced a meal at home increased the average daily calorie intake of adults by 134 calories and of teenagers by 108 calories.

Providing consumers with calorie information on menus could help consumers choose lower calorie meals when they eat out and encourage them to consume fewer calories throughout the day. Menu labeling may even prompt restaurants to improve the nutritional quality of the menu items they offer.

Years of Debate Preceded Menu-Labeling Regulations

Prior to the new regulations, Federal law only required restaurants to have nutrition information available upon request when making a nutrient-content or health claim. For example, if a menu listed an entrée as being low in fat, information about the amount of fat in the entrée had to be available upon request. Nutrition and calorie information disclosure was otherwise voluntary and did not necessarily appear on menus or menu boards. In a study conducted in Atlanta, GA, in 2004-05, researchers found that only 6.9 percent of fast-food outlets chose to place calorie information on their menu boards, and just 5.2 percent of full-service restaurants chose to print it in their menus. Many restaurants instead provided consumers with nutrition information online, in pamphlets, on tray liners, and elsewhere, requiring consumers to do the necessary research before ordering their food.

Debate over mandatory menu labeling grew in the 2000s as it became clear that eating out is associated with less healthful food choices. Opponents and proponents debated the costs for requiring restaurants to provide the information, as well as the benefits to consumers. Proponents pointed to studies showing that consumers typically underestimate the calories in restaurant foods and agreed with the American Heart Association that menu labeling was “an important part of a comprehensive approach to addressing our Nation’s obesity epidemic.” However, other organizations opposed new regulations partly on the argument that consumers can already identify more and less healthy meals. The Center for Consumer Freedom argued that, “We don’t need government to tell us the difference between salad and a 12-piece bucket of chicken.”

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, a number of State, county, and municipal governments were debating policies that would require restaurants to provide consumers with calorie and other nutrition information at the point of purchase. The first to implement such a law was New York City in 2008. This law was followed by similar laws in King County, WA; Philadelphia, PA; Montgomery County, MD; the State of California; and other jurisdictions. Many eating places in other localities without menu-labeling regulations continued to voluntarily provide nutrition information, though not always on menus. In an analysis of data from the 2007-08 and 2009-10 Flexible Consumer Behavior Survey (FCBS) modules of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), ERS researchers found that 21 percent of fast-food patrons and 17 percent of full-service restaurant patrons reported seeing nutrition information on menus.

The National Restaurant Association advocated for Federal labeling regulations, arguing that a uniform, national standard is better than “a patchwork of state and local requirements.” In 2011, the FDA issued a set of proposed rules. After considering approximately 900 comments from consumers, consumer groups, industry, and other organizations, the FDA published its final regulations in the Federal Register on December 1, 2014. FDA’s menu-labeling regulations will supersede State and local menu-labeling provisions.

Regulations Cover Restaurants and Similar Retail Food Establishments

FDA’s new calorie-labeling regulations apply to fast-food and full-service restaurants that are part of a chain with 20 or more locations doing business under the same name and offering substantially the same menu items. The regulations also apply to other chains of 20 or more locations that sell restaurant-type foods. Retail food chains such as ice cream shops, mall cookie counters, cafeterias, coffee shops, convenience stores, delicatessens, grocery stores, and food service counters at amusement parks, bowling alleys, and movie theatres are all included under the new regulations.

However, menu-labeling regulations do not cover smaller chains and independent restaurants, so Americans should not necessarily expect to see calorie information at all eating places. In addition, the regulations define 'location' to mean a fixed position or site. Therefore, foods served on trains, airplanes, and other transportation modes are not subject to the regulations. Schools are also not covered.

Menu-labeling regulations cover “standard menu items”—defined by FDA as restaurant-type foods and beverages that are routinely included on a menu or menu board or routinely offered as a self-service item or a food or beverage on display for purchase. Condiments, daily specials, temporary menu items, custom orders, and foods and beverages being test-marketed are exempt.

For foods and establishments that are subject to regulations, consumers will be seeing calorie information displayed in a clear manner, such that ordinary consumers can likely read and understand the information under customary conditions of purchase and use.

Along with this calorie information, consumers will also be seeing the following succinct statement about an individual’s daily calorie needs: '2,000 calories a day is used for general nutrition advice, but calorie needs vary.” This statement is designed to allow consumers to compare the calorie declaration for a menu item to their daily energy requirements. However, because children and adults have very different nutritional needs, FDA will also allow restaurants to use the statement, '1,200 to 1,400 calories a day is used for general nutrition advice for children ages 4 to 8 years, but calorie needs vary,' on a menu or menu board targeted to children.

While calorie information must be clearly and prominently displayed, it is not the only sort of nutrition information consumers will now have access to. Menus and menu boards must also inform consumers that additional information, such as saturated fat, carbohydrate, and sodium content, is available upon request. Such information must be available in written form and include most of the nutrition information currently provided on packaged food labels.

Menu-Labeling Information May Need To Surprise Consumers To Change Food Choices

Will the new calorie-labeling laws cause Americans to behave differently? Will they make different choices when eating out or alter their food choices at home later that day or week? How will restaurants respond to the new regulations? In two recent studies, ERS researchers began to explore these questions. One study examined the characteristics of consumers who say they currently use available nutrition information in eating places, as well as the characteristics of consumers who say they would use such information if it were available. The second study focused on whether calorie labeling of restaurant items is likely to surprise consumers with new information.

Using data from the 2007-08 and 2009-10 FCBS module of NHANES, ERS researchers found that people who already have healthier diets and practice healthy dietary habits, such as reading nutrition information on food labels in grocery stores and keeping healthy foods in their homes, were more likely to use calorie information when eating out. For example, FCBS respondents who rarely or never had dark green vegetables stored at home were as likely to go to a full-service restaurant as people who always or most of the time had dark green vegetables at home. However, the “rarely or never” group was 36 percentage points less likely to use the nutrition information on the menus as the “always or most of the time” group.

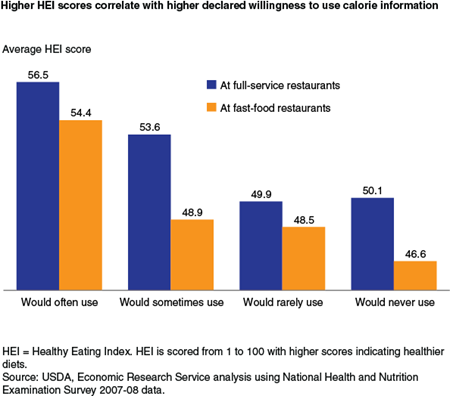

Strongly correlated with a person’s declared willingness to use nutrition information was his or her Healthy Eating Index (HEI) score, a measure of an individual’s diet quality that assesses conformance to Federal dietary guidance. People who said that they would use nutrition information “often” in both fast-food and full-service settings have the highest average HEI scores, followed by those who said they would use it “sometimes.” Both of these groups had higher HEI scores than those who said that they would “never” use nutrition information.

Menu labeling could motivate consumers to make different food choices at restaurants by reminding them about the importance of calories when eating out, but research shows that it is most likely to influence behavior when consumers learn new, surprising information. Several studies have shown that menu labeling reduces the likelihood that a consumer purchases an item if its actual calories exceed expectations but has little impact if its actual calories are consistent with expectations.

For example, in a study conducted at Oklahoma State University, researchers found that health-conscious consumers were less likely to change their behavior in response to menu labeling. They theorized that health-conscious consumers are more knowledgeable and already understand fairly well which foods are low and high in calories. These consumers are less likely to be surprised by menu labels and, indeed, may learn relatively little new information.

Given evidence that a consumer’s prior knowledge of nutrition may affect his or her response to menu labeling, a recent ERS study asked what consumers could likely figure out on their own in the absence of menu labeling. The study built on research in behavioral economics, which shows that consumers typically rely on “rules of thumb” to make inferences about products when they are not provided with explicit information. For example, a consumer may know to seek out meals rich in fruits and vegetables and to avoid side dishes like French fries and onion rings to lessen the amount of calories consumed.

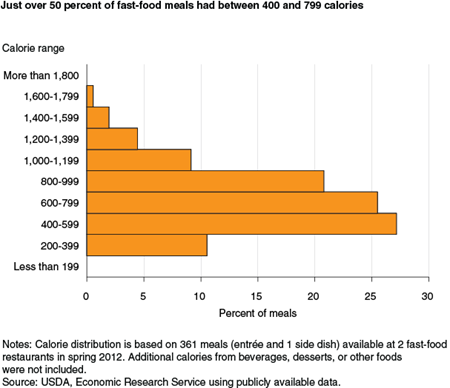

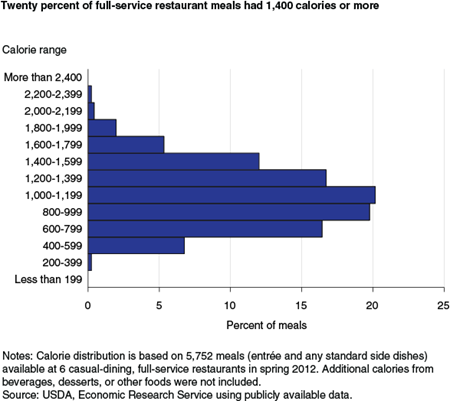

For the study, ERS researchers collected detailed information on 361 meals sold by 2 fast-food chains and 5,752 meals sold by 6 casual-dining, full-service restaurant chains in Montgomery County, MD. Meals at fast-food restaurants generally included one entrée and a side dish. Those at full-service restaurants included one entrée and any standard side dishes that come with the meal, such as a steak entrée accompanied by a choice of two sides (e.g., French fries, steamed vegetables, a baked potato, or rice). In this case, ERS researchers treated each of the six possible combinations of the entrée and two sides as a separate meal. Calorie counts for meals at both types of restaurant did not account for any additional calories consumers might order from beverages or desserts. The full-service restaurant meals were often more calorie dense; full-service restaurant meals contained between 219 and 2,350 calories, while fast-food meals ranged from 215 to 1,710 calories.

ERS researchers then measured a representative consumer’s ability to discriminate among these meals using rules-of-thumb nutrition knowledge provided by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Results show that consumers who understand the information outlined by these organizations can discriminate fairly well between substantially lower and higher choices. When comparing any 2 fast-food restaurant meals that differ by 200 calories or more, these consumers would be able to correctly identify the lower calorie option 84 to 91 percent of the time. Similarly, when comparing any 2 full-service restaurant meals with a 200-calorie-or-more difference, consumers using the AHA and NHLBI guidelines would be able to identify the lower calorie meal between 73 percent and 80 percent of the time.

However, rules of thumb were less effective for discriminating between foods that differed modestly in calorie content. For meals at fast-food and full-service restaurants that differed by less than 200 calories, consumers that draw on the same AHA and NHLBI guidelines would only have about a 50-percent chance of identifying the lower calorie option, suggesting that the rules have little or no discriminatory value in this range. Moreover, without the help of menu labeling, consumers may still underestimate the total calorie content of restaurant meals or not know how that number relates back to their daily energy needs. While many Americans may already be making choices between low- and high-calorie foods based on their current nutrition knowledge, menu labeling will allow them to refine their choices.

Menu Labeling Could Impact Consumer Behavior in a Variety of Ways

Obtaining calorie information and using it are two separate actions. Food choices made while eating out reflect a variety of factors: taste, desire to indulge, time constraints, and the economists' favorite—price. In interviews conducted in Philadelphia, PA, in 2011 at a full-service restaurant subject to local menu-labeling requirements, 76 percent of interviewees noticed the calorie labels, and 26 percent reported that this influenced their ordering decisions. In Pierce County, WA, 71 percent of customers interviewed at full-service restaurants participating in voluntary menu labeling in 2009 noticed the calorie information, and 20.4 percent claimed to have chosen a lower calorie entrée. Other studies have found that responses to calorie disclosure on menus and menu boards varied from consumers ordering foods with an average of 155 fewer calories to no decrease in calories ordered.

If consumers are not swayed by menu labeling to choose lower calorie foods and beverages when they eat away from home, could it still motivate them to reduce their calorie consumption elsewhere throughout the day? The statement about an individual’s daily calorie needs that is required to be displayed on menus and menu boards may have an impact on total daily calorie consumption. A study by researchers at Yale University found that consumers whose menus included a similar statement did reduce their calorie intake over the course of the entire day, including foods consumed after leaving the restaurant.

Recipe adjustments offer another avenue for dietary improvements. Mandatory labeling of menu items and dishes could encourage restaurants to introduce new, lower calorie foods and reformulate existing menu items to be lower in calories. Many restaurant chains are offering “skinny” menus, with foods that have been sautéed rather than fried, less rich sauces, and smaller portions. Such changes to restaurant menus could ultimately benefit all consumers. New low-calorie entrees and side dishes and “lighter” traditional favorites will offer all consumers—not just those who read and use nutrition labels—healthier options when dining out.

Menu Labeling Imparts New Information About the Calorie Content of Restaurant Foods, by Hayden Stewart, Jeffrey Hyman, and Diansheng Dong, USDA, Economic Research Service, December 2014

Consumers' Use of Nutrition Information When Eating Out, by Christian A. Gregory, Ilya Rahkovsky, and Tobenna D. Anekwe, USDA, Economic Research Service, June 2014

How Food Away From Home Affects Children's Diet Quality, by Lisa Mancino, Jessica E. Todd, Joanne Guthrie, and Biing-Hwan Lin, USDA, Economic Research Service, October 2010

The Impact of Food Away From Home on Adult Diet Quality, by Jessica E. Todd, Lisa Mancino, and Biing-Hwan Lin, USDA, Economic Research Service, February 2010

Nutrition Labeling in the Food-Away-From-Home Sector: An Economic Assessment, by Jay Variyam, USDA, Economic Research Service, April 2005