ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Friday, September 20, 2019

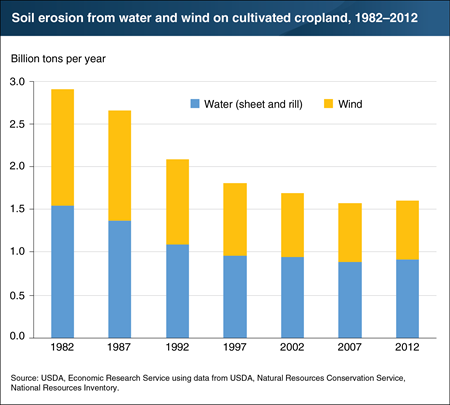

As farmers have adopted soil health and conservation practices like conservation tillage, they have helped reduce soil erosion on the Nation’s working lands. Data from USDA’s National Resources Inventory (NRI) show erosion on cultivated cropland due to water and wind has declined by 45 percent, from 2.9 billion tons in 1982 to 1.6 billion tons in 2012. Though part of this decline is due to less land being cropped over time, a larger portion is due to changes in farm management practices. Reducing erosion is an important first step toward improving soil health, which can increase yields in crop and forage production. Healthy soil also has a positive impact on water quality, decreasing nutrient runoff into streams and rivers. In addition, healthier soil tends to have a greater ability to hold water, which can give crops greater drought resilience. This chart appears in the May 2019 ERS report, Agricultural Resources and Environmental Indicators, 2019. It is also in the August 2019 Amber Waves feature, “Conservation Trends in Agriculture Reflect Policy, Technology, and Other Factors.”

Friday, September 6, 2019

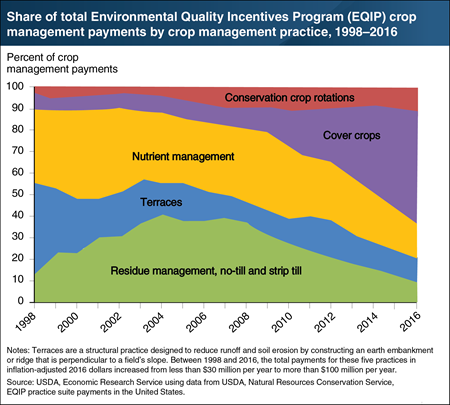

USDA conservation programs provide nearly $6 billion annually for financial and technical assistance to support the adoption of conservation practices on U.S. farms. This conservation effort relies mainly on voluntary incentive programs. The largest single conservation program (in terms of budget) is the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which provides funding for the retirement of environmentally sensitive land. However, the largest share of conservation funding goes toward incentivizing conservation practices on lands that remain in production, or “working lands.” The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) is one such program, which provides financial assistance to farmers who adopt or install conservation practices on land in agricultural production. EQIP expenditures for crop management practices focused on five categories of practices—conservation crop rotations, cover crops, nutrient management, terraces, and conservation tillage (residue management). Farmers who use cover crops grow a crop (often over the winter) that will be left in place as residue or incorporated into the soil to increase organic matter. Between 1998 and 2016, the share of EQIP expenditures going to nutrient management and terracing decreased, while the share of expenditures going to cover crops increased. This chart appears in the May 2019 ERS report Agricultural Resources and Environmental Indicators, 2019. Also see the August 2019 Amber Waves feature, “Conservation Trends in Agriculture Reflect Policy, Technology, and Other Factors.”

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

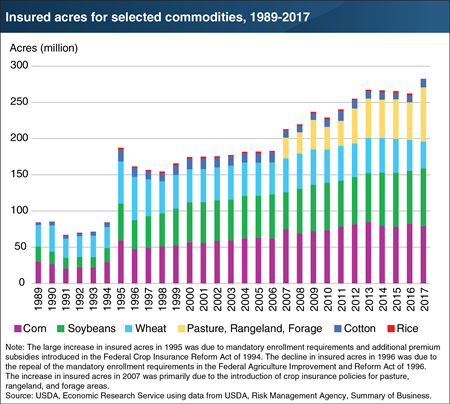

The 2018 Farm Act continues to emphasize support for farm risk management and to expand coverage within the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) that was established in the 2014 Farm Act. Since 2007, the largest growth in insured acres has come from the introduction of coverage for pasture, rangeland, and forage areas. The 2018 Farm Act introduces a catastrophic coverage option for these policies, which is likely to further increase the total acres insured for pasture, rangeland, and forage areas. Premiums for catastrophic coverage policies are fully subsidized (farmers pay no premium, only an administrative fee), while higher levels of coverage are only partially subsidized (farmers pay part of the premium). The availability of cheaper policies may induce additional participation in FCIP. However, the county base values that are used to assess the economic value of insured production covered by pasture, rangeland, and forage policies will be lower in the 2019 crop year than in previous years. In turn, this decrease lowers the value of insured hay and forage production and may reduce the demand for pasture, rangeland, and forage area policies. This chart appears in the ERS crop insurance topic page of The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018: Highlights and Implications, published February 2019.

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

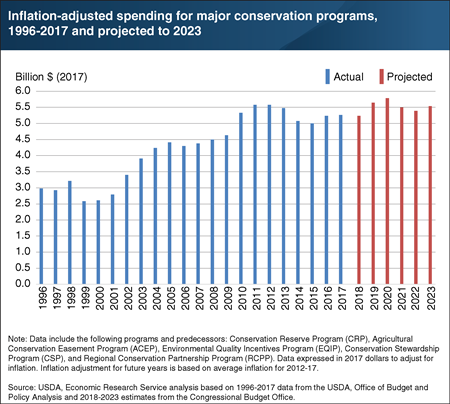

Voluntary conservation incentive programs are the backbone of U.S. agricultural conservation policy. For fiscal years 2019 to 2023, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects mandatory spending on conservation programs under the 2018 Farm Act would be $555 million higher than baseline (projected) spending if the previous 2014 Farm Act had remained in force. That represents an increase of about 2 percent. Nearly all of this spending will flow through five programs: the Conservation Reserve Program, Conservation Stewardship Program, Environmental Quality Incentives Program, Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, and Regional Conservation Partnership Program. For these programs and their predecessors, inflation-adjusted spending increased under both the 2002 and 2008 Farm Acts (2002-2013) but was lower under the 2014 Farm Act (2014-2018). CBO projections suggest that the 2018 Farm Act will provide slightly higher funding, on average, than the 2014 Farm Act. Although program funding is mandatory and does not require appropriations, spending in future years is subject to congressional review and has sometimes been reduced from levels specified in the Farm Acts. This chart appears in the ERS topic page The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018: Highlights and Implications, updated February 2019.

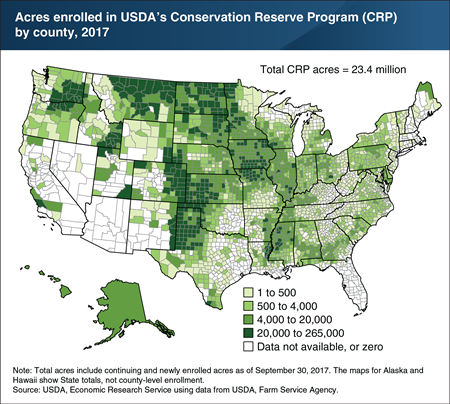

Monday, December 3, 2018

As of the end of fiscal year 2017, USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) covered 23.4 million acres of environmentally sensitive land. With an annual budget of $1.8 billion, CRP was USDA’s largest conservation program in terms of spending at that time. Enrollees receive annual rental and other incentive payments for taking eligible land out of production for 10 years or more. Program acreage tends to be concentrated on marginally productive cropland that is susceptible to erosion by wind or rainfall. A large share of CRP acreage is located in the Great Plains (from Texas to Montana), where rainfall is limited and much of the land is subject to potentially severe wind erosion. Smaller concentrations of CRP land are found in eastern Washington, southern Iowa, northern Missouri, southern Idaho, and the Mississippi Delta. This chart appears in the ERS data product Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials, updated October 2018.

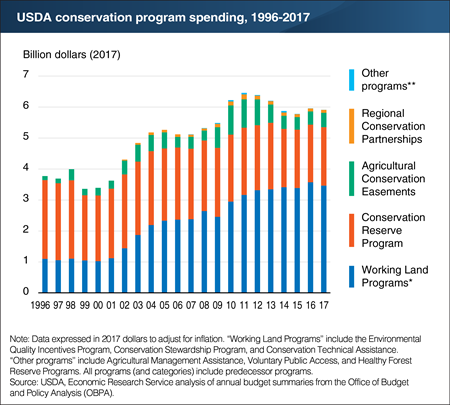

Friday, May 4, 2018

USDA agricultural conservation programs provide technical and financial assistance to farmers who adopt and maintain practices that conserve resources or enhance environmental quality. Although USDA implements more than a dozen individual conservation programs, nearly all assistance is channeled through six: the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), Conservation Technical Assistance (CTA), Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), and the Resource Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). EQIP, CSP, and CTA are often referred to as “Working Land Programs” because they focus primarily on supporting conservation on land in agricultural production (crops or grazing). The 2014 Farm Act continued to emphasize working land conservation. Between 2012 and 2017, combined funding for Working Land Programs accounted for more than 50 percent of spending in USDA conservation programs. This emphasis reflects a long-term trend—begun under the 2002 Farm Act—that increased annual spending in Working Land Programs. In 2017 dollars (to adjust for inflation), this spending increased from roughly $1 billion under the 1996 Farm Act to more than $3 billion under the 2014 Act. This chart updates data found in the May 2014 Amber Waves feature, "2014 Farm Act Continues Most Previous Trends In Conservation."

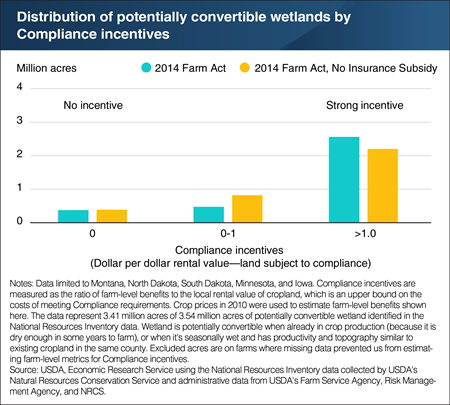

Wetland Compliance incentives are strong in Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa

Tuesday, February 27, 2018

Wetlands provide a wide range of ecosystem services in all parts of the United States. For most U.S. agricultural programs, farmers who receive benefits must refrain from draining wetlands on their farm. The 2014 Farm Act re-linked crop insurance premium subsidies to this provision, known as Wetland Compliance (WC), for the first time since 1996. ERS researchers examined the effect of premium subsidies on farmer’s compliance incentives under the 2014 Farm Act. (Because of data limitations, ERS researchers focused on States that include the Prairie Pothole region: Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa, where wetland habitat is critical to ducks and other migratory birds.) In Prairie Pothole States, WC incentives are strong. When the compliance incentive includes premium subsidies, an estimated 75 percent (2.6 million acres) of potentially convertible wetland is on farms where Compliance incentives (farm program benefits) are clearly large enough to offset revenue lost by not draining these lands for crop production. Severing the link between WC and crop insurance premium subsidies (while continuing the link between Compliance and other 2014 Farm Act programs) would reduce the number of potentially convertible wetlands with strong protection by 15 percent (from 2.6 to 2.2 million acres). This chart appears in the July 2017 report, Conservation Compliance: How Farmer Incentives Are Changing in the Crop Insurance Era.

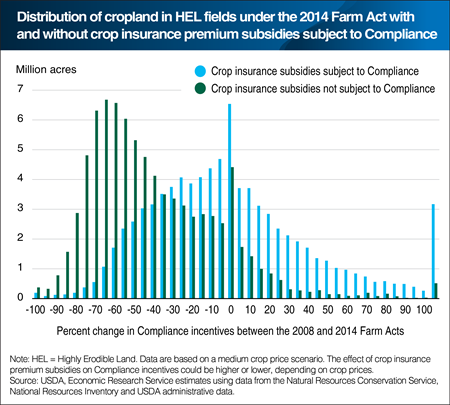

Wednesday, November 1, 2017

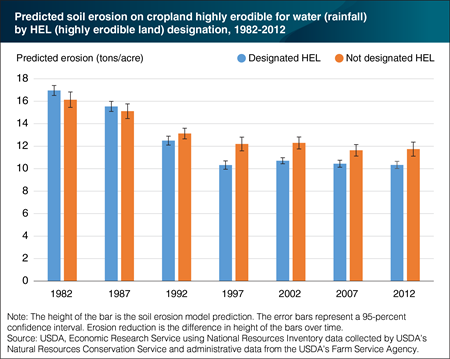

To be eligible for most U.S. farm program benefits, participating farmers must apply soil conservation systems on cropland that is particularly vulnerable to soil erosion. The 2014 Farm Act re-linked crop insurance premium subsidies to this provision, known as Highly Erodible Land Compliance (HELC), for the first time since 1996. These premium subsidies account for a significant share of Compliance incentives—typically between 30 and 40 percent, depending on crop prices. The 2014 Act also included major changes in other Compliance-linked programs, including the elimination of Direct Payments, a large program under the 2008 Farm Act. On individual farms, Compliance-linked benefits could be higher or lower than they would have been under a continuation of the 2008 Act. Under the 2014 Act (blue bars), ERS researchers estimated that less than 10 million acres are on farms that would have experienced a 50-percent or larger decline in Compliance incentives between the two Farm Acts given crop prices similar to 2010 levels. If premium subsidies were not subject to Compliance (green bars), more than 40 million acres of cropland in HEL fields would be on farms where Compliance incentives would decline by 50 percent or more. This chart appears in the July 2017 Amber Waves feature, "Conservation Compliance in the Crop Insurance Era."

Friday, September 15, 2017

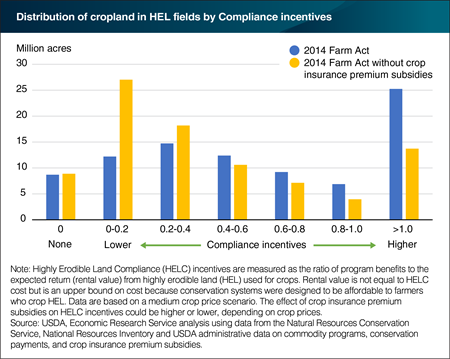

Most U.S. agricultural programs that provide payments to farmers require participating farmers to apply soil conservation systems on cropland that is particularly vulnerable to soil erosion. ERS research shows that this provision, Highly Erodible Land Compliance (HELC), is effective in reducing soil erosion when the farm program benefits that could be lost due to noncompliance exceed the cost of meeting conservation requirements. Under the 2014 Farm Act, some programs previously linked to HELC were eliminated, while new ones were created. In addition, crop insurance premium subsidies were re-linked to HELC for first time since 1996. Twenty-five million acres of highly erodible cropland are estimated to be in farms with relatively strong Compliance incentives (rightmost bars) under the Act. Without premium subsidies, farms with this level of HELC incentive would include only 14 million acres of highly erodible cropland. By comparison, farms with relatively weak Compliance incentives (the second and third sets of bars) include an estimated 27 million acres of highly erodible cropland. Without premium subsidies, farms with this level of HELC incentive would include an estimated 45 million acres of highly erodible cropland. A version of this chart appears in the ERS report, Conservation Compliance: How Farmer Incentives Are Changing in the Crop Insurance Era, released July 2017.

Monday, August 7, 2017

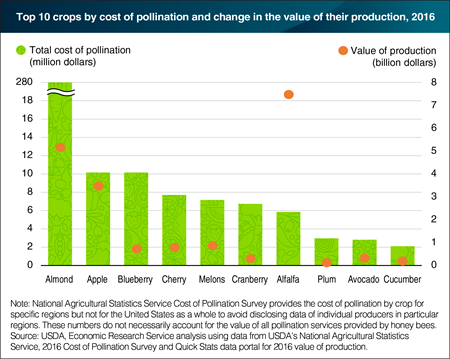

Farmers growing crops that depend on pollination can rely on wild pollinators in the area or pay beekeepers to provide honeybees or other managed bees, such as the blue orchard bee. In 2016, U.S. farmers paid $354 million for pollination services. Producers of almonds alone accounted for 80 percent of that amount—over $280 million. By comparison, producers of apples and blueberries paid about $10 million each. Pollination services helped support the production of these crops—which, in 2016, had a total production value of about $5.2 billion for almonds, $3.5 billion for apples, and $720 million for blueberries. Between 2007 and 2016, the production value of almonds grew by 85 percent in real terms, while the production value of both apples and blueberries grew by about 15 percent. Over the same period, the number of honey-producing colonies grew by 14 percent. This chart uses data found in the ERS report Land Use, Land Cover, and Pollinator Health: A Review and Trend Analysis, released June 2017.

Friday, July 28, 2017

Conservation Compliance ties eligibility for most Federal farm program benefits to soil and wetland conservation requirements. Under Highly Erodible Land Conservation (HELC), for example, farmers who grow crops in fields designated as highly erodible land (HEL) must apply an approved conservation system—one or more practices that work together to reduce soil erosion. ERS researchers used a statistical model to compare water (rainfall) erosion on cropland in HEL fields to similar cropland not in HEL fields. Between 1982 and 1997, soil erosion reductions were significantly larger in HEL fields (39 percent, or 6.6 tons per acre) than in those not designated as HEL fields (24 percent, or 3.9 tons per acre). The difference—about 2.7 tons per acre—is statistically different from zero, suggesting that HELC did make a significant difference in soil erosion reduction. During 1997-2012, after the initial implementation of HELC was complete, ERS analysis finds that these soil conservation gains were maintained. This chart appears in the July 2017 Amber Waves feature, "Conservation Compliance in the Crop Insurance Era."

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

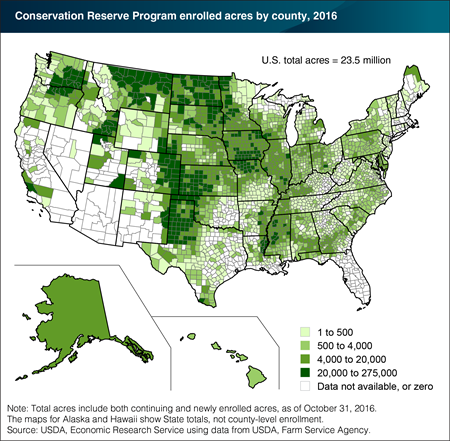

As of the end of 2016, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) covered about 23.5 million acres of environmentally sensitive land in the United States. With a $1.8 billion annual budget, CRP is currently USDA’s largest conservation program in terms of spending. Farmers who enroll in CRP receive annual rental and other incentive payments for taking eligible land out of production for 10 years or more. Program acreage tends to be concentrated on marginally productive cropland that is susceptible to erosion by wind or rainfall. A large share of CRP land is located in the Plains (from Texas to Montana), where rainfall is limited and much of the land is subject to potentially severe wind erosion. Smaller concentrations of CRP land are found in eastern Washington, southern Iowa, northern Missouri, and the Mississippi Delta. This chart appears in the ERS data product Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials, updated March 2017.

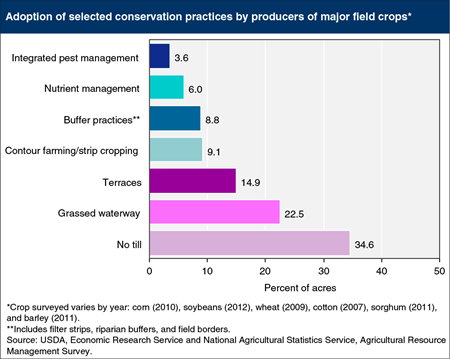

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

The environmental effects of agricultural production, e.g., soil erosion and the loss of sediment, nutrients, and pesticides to water, can be mitigated using conservation practices. Some practices are more widely adopted than other practices; no conservation practice has been universally adopted by U.S. farmers. Variation in conservation practice adoption is due, at least in part, to variation in soil, climate, topography, crop/livestock mix, producer management skills, and financial risk aversion. These factors affect the onfarm cost and benefit of practice adoption. Presumably, farmers will adopt conservation practices only when the benefits exceed cost. Government programs can increase adoption rates by helping defray costs. The potential environmental gain also varies—ecosystem service benefits (such as improved water quality and enhanced wildlife habitat) depend both on the practice and on the location and physical characteristics of the land. This chart is based on data from ARMS Farm Financial and Crop Production Practices.

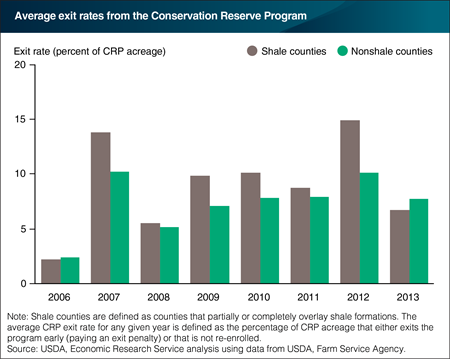

Thursday, September 1, 2016

Hydraulic fracturing for natural gas and oil trapped in shale formations has diverse impacts on agriculture. Farmers in shale regions have the potential to receive lease or royalty payments, but may face competition with energy companies for labor, water, and transportation infrastructure, and may also have an increased risk of soil or water contamination. In addition, shale energy development may affect farmers’ participation in certain USDA programs, such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). CRP covered about 27 million acres of environmentally sensitive land at the end of 2013, with enrollees receiving annual rental and other incentive payments for taking eligible land out of production for 10 years or more. About 28 percent of CRP land is located in counties that overlay shale formations (“shale counties”). From 2007 to 2012, the CRP exit rate (including early exits and non-reenrollments) was greater, on average, in shale counties than in non-shale counties. Early exits and decisions not to re-enroll could be due to a number of factors, including the placement of oil or natural gas wells, pipelines, and access roads through CRP land. For acres that exit the CRP, landowners must pay an early-exit penalty, which is the sum of all CRP payments received since enrollment plus interest. This chart is found in the ERS report, Trends in U.S. Agriculture’s Consumption and Production of Energy: Renewable Power, Shale Energy, and Cellulosic Biomass, released on August 11, 2016.

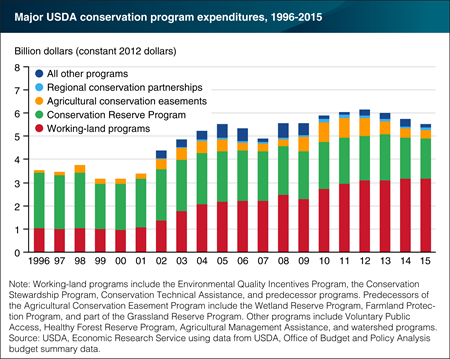

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

USDA relies mainly on voluntary programs providing financial and technical support to encourage farmers to conserve natural resources and protect the environment. In inflation adjusted terms, USDA conservation program expenditures increased by roughly 70 percent between 1996 and 2012. Much of the increases in real spending over this period occurred in working land programs and agricultural easements. Working land programs provide assistance to farmers who install or maintain conservation practices (such as nutrient management, conservation tillage, and the use of field-edge filter strips) on land in crop production and grazing. Agricultural easements provide long-term protection for agricultural land and wetlands. The Conservation Reserve Program—which pays farmers to remove environmentally sensitive land from production and encourages partial-field practices such as using grass waterways and riparian buffers—is still USDA’s largest conservation program, but has slowly ebbed in prominence. While real spending on USDA conservation programs rose under the 2002 Farm Act (2002-07) and the 2008 Farm Act (2008-13), the 2014 Farm Act reduced mandatory spending, and expenditures over 2014 and 2015 appear to be leveling off. This chart is found in the Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials data product on the ERS website.

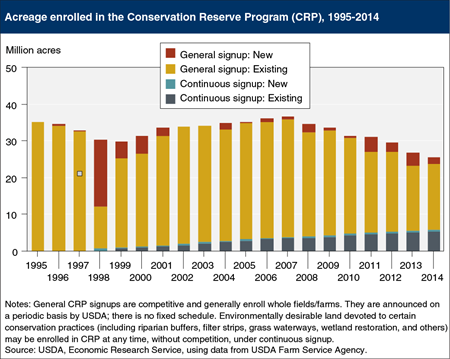

Thursday, June 25, 2015

The Agricultural Act of 2014 gradually reduces the cap on land enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) from 32 million acres to 24 million acres by 2017. CRP acreage declined 34 percent since 2007, falling from 36.8 million acres to 24.2 million by April 2015. Environmental benefits may not be diminishing as quickly as the drop in enrolled acreage might suggest. While initially enrolling mainly whole fields or farms (through periodically announced general signups), CRP increasingly uses “continuous signup” (which has stricter eligibility requirements than general signup) to enroll high-priority parcels that often provide greater per-acre environmental benefits. Conservation practices on these acres include riparian buffers, filter strips, grassed waterways, and wetland restoration. Riparian buffers, for example, are vegetated areas that help shade and partially protect a stream from the impact of adjacent land uses by intercepting nutrients and other materials, and provide habitat and wildlife corridors. Enrollment under continuous signup increased by about 50 percent, from 3.8 million acres in 2007 to 5.7 million acres in 2014. A version of this chart is found on the ERS web page, Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications (Conservation).

Monday, June 1, 2015

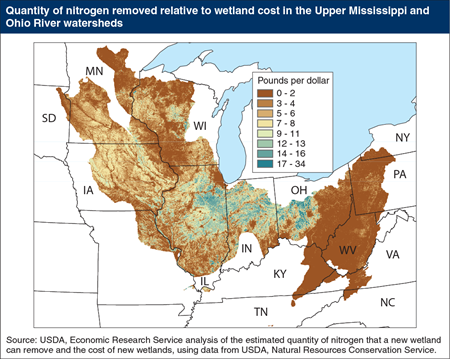

Every year, agriculture contributes an estimated 60-80 percent of delivered nitrogen and 49-60 percent of delivered phosphorous in the Gulf of Mexico. Nitrogen in waters can cause rapid and dense growth of algae and aquatic plants, leading to degradation in water quality as found in the hypoxic zone of the Gulf of Mexico, where excess nutrients have depleted oxygen needed to support marine life. Nitrogen removal is one of the many benefits of wetlands. An ERS analysis found that on an annual basis, the amount of nitrogen removed per dollar spent to restore and preserve a new wetland ranged from 0.15 to 34 pounds within the area of study (the Upper Mississippi/Ohio River watershed), or a range of $0.03 to $7.00 per pound of nitrogen removed. Restoring and protecting wetlands in the very productive corn-producing areas of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio tends to be more cost effective than elsewhere in the study area. The study suggests that if nitrogen reduction was the only environmental goal, these corn-producing areas would be a good place to restore wetlands. Hydrologic conditions in the Upper Mississippi and Ohio River watersheds are unique, so the cost effectiveness of wetlands elsewhere is uncertain. This map is found in the ERS report, Targeting Investments To Cost Effectively Restore and Protect Wetland Ecosystems: Some Economic Insights, ERR-183, February 2015.

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

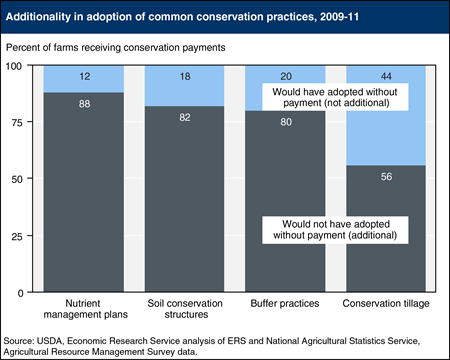

Under the Agricultural Act of 2014, Congress provided an estimated $28 billion in mandatory 2014-18 funding for USDA conservation program payments that encourage farmers to adopt conservation practices. If farmers would have adopted the practice even without financial incentive, however, the practices are not “additional,” and the payments provide income for farmers without improving environmental quality. Some farmers have adopted specific conservation practices without receiving payments because doing so reduces production costs or preserves the long-term productivity of their farmland (e.g., conservation tillage). Many other farmers have not adopted conservation practices, presumably because the cost of doing so exceeds expected onfarm benefits, the value of which can vary based on many factors, including soil, climate, topography, crop/livestock mix, producer management skills, and risk aversion. Since the value of onfarm benefits can vary widely across practices and farms, identifying which farmers will adopt a conservation practice only if they receive a payment is not straightforward. Additionality tends to be high for practices that are expensive to install, have limited onfarm benefits, or onfarm benefits that accrue only in the distant future (e.g., soil conservation structures, buffer practices, and written nutrient management plans). Practices that can be profitable in the short term are more likely to be adopted without payment assistance and tend to be less additional (e.g., conservation tillage). Research indicates that the likelihood a payment will result in additional environmental benefit increases as the implementation cost of the conservation practice increases (such as soil conservation structures) and its impact on farm profitability declines. This chart is based on data from the ERS report, Additionality in U.S. Agricultural Conservation and Regulatory Offset Programs, ERR-170, July 2014.

Friday, April 10, 2015

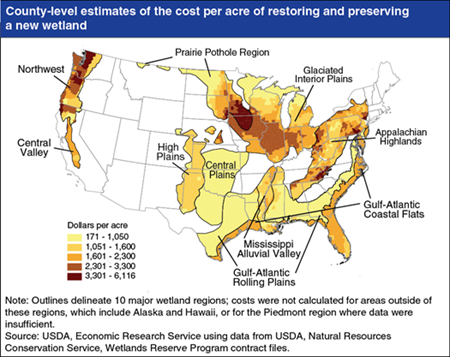

USDA’s costs of restoring and preserving new wetlands across the contiguous United States range from about $170 to $6,100 per acre, with some of the lowest costs in western North Dakota and eastern Montana and the highest in major corn-producing areas and western Washington and Oregon. To analyze conservation program expenditures, ERS researchers generated county-level estimates of wetland costs for each of the major wetland regions as designated by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (outlined in black in the map), using primarily NRCS Wetland Reserve Program contract data. Variations in costs are driven by differences in land values and the complexity of restoring hydrology and wetland ecosystems. Information about how the costs of restoring and preserving wetlands vary spatially (together with the relative benefits) can inform wetland targeting policies within States/regions and across the U.S. This map is found in the ERS report, Targeting Investments to Cost Effectively Restore and Protect Wetland Ecosystems: Some Economic Insights, ERR-183, February 2015.

Thursday, August 21, 2014

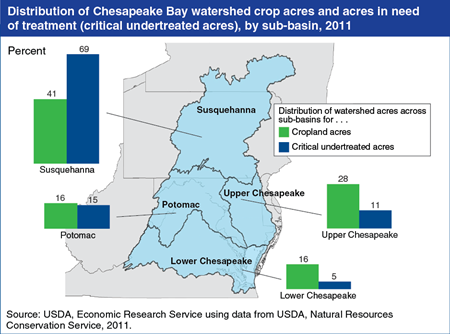

The Chesapeake Bay is North America’s largest and most biologically diverse estuary, and its watershed covers 64,000 square miles across 6 States (Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia. In 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency established limits for nutrient and sediment emissions from point (e.g., wastewater treatment plants) and nonpoint (e.g., agricultural runoff) sources to the Chesapeake Bay in the form of a total maximum daily load (TMDL). Agriculture is the largest single source of nutrient emissions in the watershed. About 19 percent of all cropped acres in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are critically undertreated, meaning that the management practices in place are inadequate for preventing significant losses of pollutants from these fields. Critically undertreated acres are not distributed among the four sub-basins in the same way as cropland. For example, the Susquehanna watershed contains 69 percent of critically undertreated acres but only 41 percent of cropland. Targeting conservation resources to highly vulnerable regions could improve the economic performance of environmental policies and programs. This chart displays data found in the ERS report, An Economic Assessment of Policy Options To Reduce Agricultural Pollutants in the Chesapeake Bay, ERR-166, June 2014.