ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

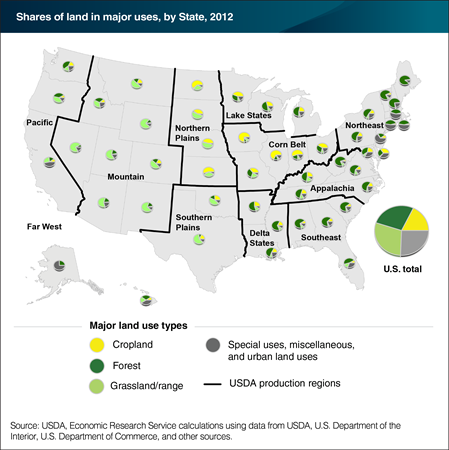

The ERS Major Land Uses (MLU) series is the longest running, most comprehensive accounting of all major uses of public and private land in the United States. The series was started in 1945, and has since been published about every 5 years using the latest data from the National Agricultural Statistics Service’s Census of Agriculture. In the 2012 MLU data (the latest available), grassland pasture and range was the most common land use in the United States, representing 29 percent of U.S. land. The second most common was forest-use—land capable of producing timber or covered by forest and used for grazing—at 28 percent. The distribution of land use varies substantially across the country, based on factors such as soil, climate, and Federal and local policies and programs. Cropland is concentrated in the Corn Belt and Northern Plains regions, where several States (including Iowa, Kansas, and Illinois) have more than half of their land base devoted to cropland. Grassland pasture and range accounted for a large share of land in the Mountain (60 percent) and Southern Plains (59 percent) regions. The share of forest-use land was highest along the eastern seaboard in the Southeast (62 percent), Northeast (59 percent), Delta States (58 percent), and Appalachia (57 percent) regions. This chart appears in the ERS report Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2012, released August 2017.

Monday, August 7, 2017

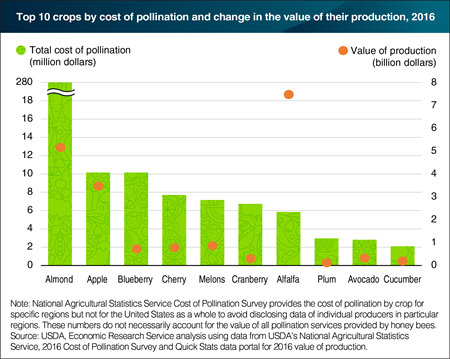

Farmers growing crops that depend on pollination can rely on wild pollinators in the area or pay beekeepers to provide honeybees or other managed bees, such as the blue orchard bee. In 2016, U.S. farmers paid $354 million for pollination services. Producers of almonds alone accounted for 80 percent of that amount—over $280 million. By comparison, producers of apples and blueberries paid about $10 million each. Pollination services helped support the production of these crops—which, in 2016, had a total production value of about $5.2 billion for almonds, $3.5 billion for apples, and $720 million for blueberries. Between 2007 and 2016, the production value of almonds grew by 85 percent in real terms, while the production value of both apples and blueberries grew by about 15 percent. Over the same period, the number of honey-producing colonies grew by 14 percent. This chart uses data found in the ERS report Land Use, Land Cover, and Pollinator Health: A Review and Trend Analysis, released June 2017.

Friday, June 30, 2017

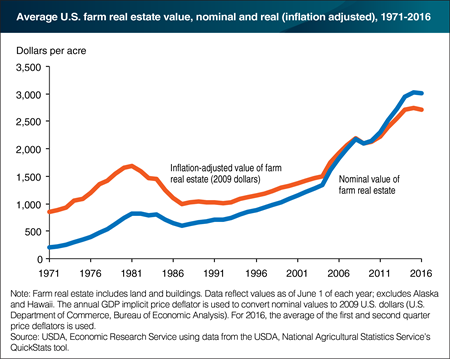

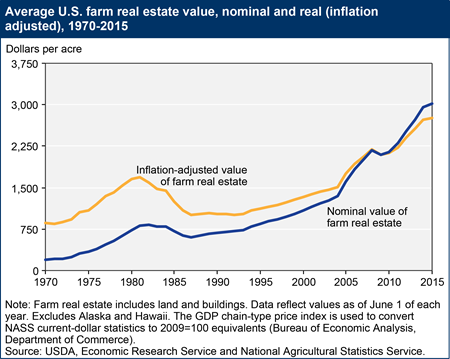

In recent years, farm real estate (including farmland and buildings) has accounted for about 80 percent of the value of U.S. farm assets—amounting to about $2.4 trillion in 2015. Strong farm earnings and historically low interest rates have supported the increase in farmland values since 2009. Since 2014, farm real estate values in many regions have leveled off; and, in 2016, the national average per-acre value declined slightly. This is partly a response to the recent declines in farm income, which may temper expectations of future farm earning potential. In addition, the 2016 USDA 10-year commodity outlooks suggest that the prices of major commodities will all stabilize at, or grow modestly from, their current price levels—which are significantly lower than those in 2011. Expectations of interest rate increases, which have been noted in some U.S. farm regions, also put downward pressure on land values. Given that farm real estate makes up such a significant portion of the balance sheet of U.S. farms, changes in its value can affect the financial well-being of individual farms and the farm sector. Over 60 percent of U.S. farmland was owner-operated in 2014; for these owners, increases in real estate values make it easier to obtain credit and service debt. For the farmers who rent the remaining 39 percent of farmland, higher real estate values can lead to higher rent expenses. This chart appears in the ERS topic page for Farmland Value, updated April 2017.

Friday, April 28, 2017

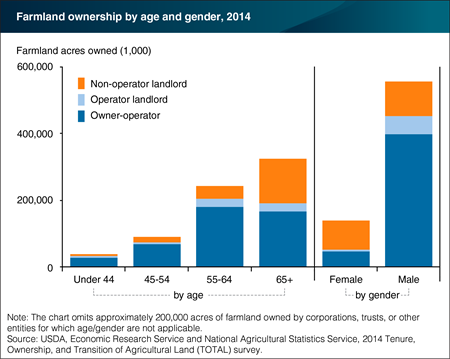

The Tenure, Ownership, and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) survey provides demographic information that can reveal trends about who owns and rents U.S. farmland. In 2014, for example, 61 percent of U.S. farmland was owned by the farm operator (or owner-operated); those aged 55 and older accounted for nearly 80 percent of that land. By comparison, out of the 39 percent of farmland that was rented out, 80 percent was owned by non-operator landlords; nearly 70 percent of that land was owned by someone aged 65 or older. Building up the financial capacity to purchase farmland takes time, which contributes to the relatively advanced age of landowners. Farmland ownership also varies by gender, with male principal operators accounting for the majority of land (90 percent) owned by both owner-operators and operator landlords. However, land owned by non-operator landlords was more equally divided by gender, with women owning 46 percent of that land. This chart appears in the ERS data visualization 2014 Tenure, Ownership, and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) survey, released March 2017.

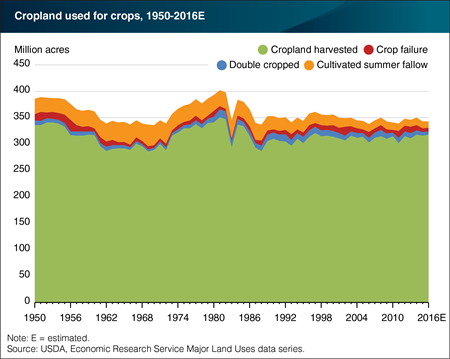

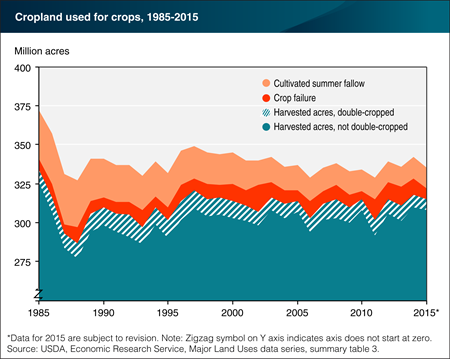

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

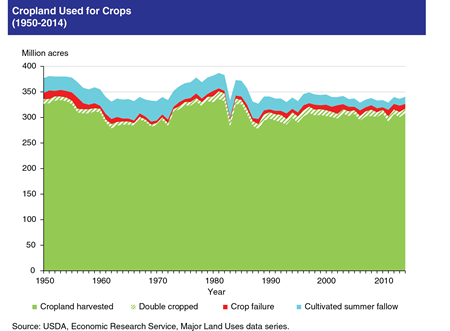

The ERS Major Land Uses (MLU) series estimates land in various uses, including the acres devoted to crop production in a given year. These acres, collectively referred to as “cropland used for crops,” include acres of cropland harvested, acres on which crops failed, and cultivated summer fallow. At 318 million acres, cropland harvested in 2016 is estimated to have increased by 2 million acres from the previous year—returning to levels in 2014 and matching the highest cropland harvested area since 1997 (321 million acres). The area that was double cropped (two or more crops harvested) declined by 1 million acres, while land that experienced crop failure held constant at 7 million acres in 2016—remaining well below its 20-year average of 10 million acres. Cultivated summer fallow, which primarily occurs as part of wheat rotations in the semiarid West, continued its long-term decline and reached its lowest level (12 million acres) since the start of the MLU series. The larger historical fluctuations seen in cropland used for crops are largely attributable to Federal cropland acreage reduction programs, such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Initiated in 1985, the CRP pays farmers to keep idle environmentally sensitive land that could otherwise be used in crop production. This chart uses historical data from the ERS MLU series, recently updated to include 2016 estimates.

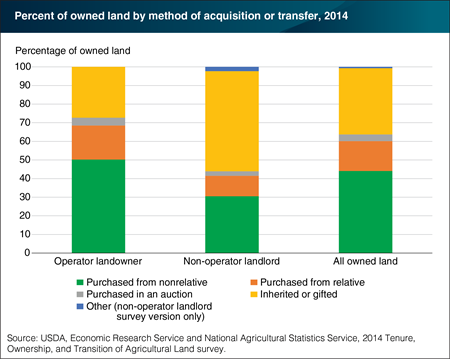

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

Land may be acquired in a number of ways, including sales, gifts, and inheritances. Arms-length purchases from nonrelatives are a traditional method for acquiring land, particularly for those without family or personal connections to agricultural landowners. In 2014, operating landowners—those who own farmland and operate some or all of it—purchased half of their land from nonrelatives. This group acquired another 27 percent of land through inheritances or gifts. In contrast, non-operator landlords—those who own and rent farmland but are not actively involved in its operation—acquired 30 percent of their land in purchases from nonrelatives. The majority of non-operator land (54 percent) was inherited or received as a gift. Since most farming operations are family farms, it is not surprising that a larger share of operator landowners’ land (18 percent) was purchased from a relative compared to non-operators (11 percent), as this suggests that land is being sold from one family generation to the next. This chart appears in the August 2016 Amber Waves feature, “Land Acquisition and Transfer in U.S. Agriculture.”

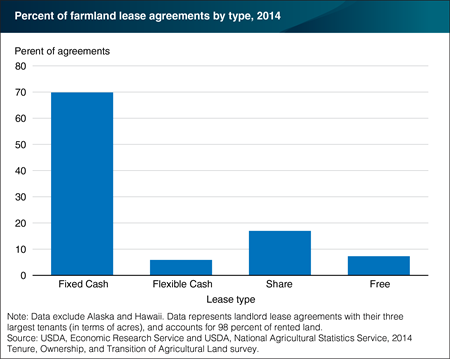

Thursday, November 3, 2016

In the contiguous 48 States, about 354 million acres (or 39 percent) of U.S. farmland were rented in 2014. Eighty percent of that rented land was owned by non-operator landlords who are not actively engaged in a farm operation, while the remainder was rented from one farm operator to another. Farmland may be rented out under a fixed rental rate per acre (fixed cash), a rate that depends on post-harvest crop prices or yields (flexible cash), or an agreement where the landlord receives a portion of produced output (share). A landlord may also let a tenant use the land for free. In 2014, approximately 70 percent of leases used a fixed cash rent payment. Share-based agreements were the second most common contract type, used in 17 percent of leases. Both flexible cash and free agreements accounted for less than 10 percent of agreements. Fixed cash made up the majority of agreements across different U.S. regions and landlord subtypes, such as individual and corporate ownership entities. This illustrates the broad shift from share to cash agreements in recent years: in 1999, 57 percent of leases used a fixed cash agreement and 21 percent a share agreement. A version of this chart appeared in the ERS report U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer, released on August 25, 2016.

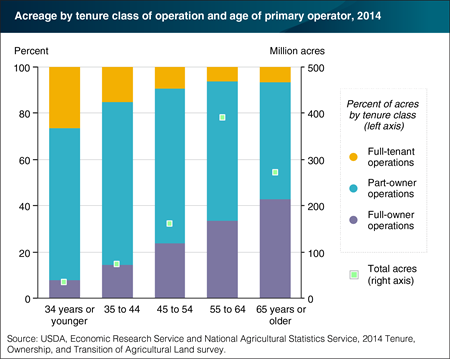

Monday, September 12, 2016

Farms can be classified as full-owner, part-owner, or full-tenant operations based on whether the farmer owns all, some, or none of the land in the operation. In 2014, 60 percent of farmland acres in the United States were found in part-owner operations, 32 percent in full-owner operations, and 8 percent in full-tenant operations. Acreage in full-tenant operations make up a much higher share—27 percent of acres operated—for younger farmers, and much less—7 percent—for farmers 65 or older. It can take time for farmers to build up the financial capacity to purchase land outright; rental agreements can help young farmers and ranchers gain access to land during this time. The majority of farmland, nearly three-fourths of U.S. acreage, is operated by farmers 55 and older, who account for 83 percent of all land in full-owner operations. A version of this chart is found in the ERS report, U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer, released on August 25, 2016.

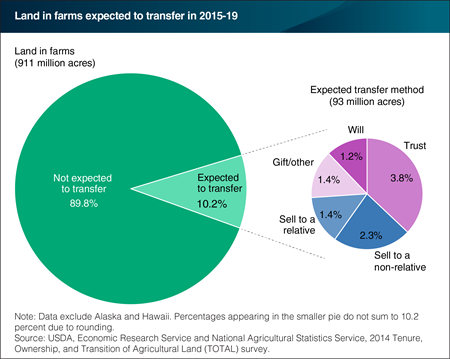

Friday, August 26, 2016

The relatively advanced age of the U.S. farming population—about a third of principal farm operators in 2014 were at least age 65 compared with 12 percent of self-employed workers in nonagricultural businesses—has sparked interest in the manner in which land will be transferred to other landowners, including the next generation of farm operators. Farmland owners planned to transfer 93 million acres in the next 5 years (2015-19)—10 percent of all land in farms—through a variety of means. Landowners anticipated selling 3.8 percent of all farmland, with just 2.3 percent planned to be sold to non-relatives. A larger share of land (6.5 percent) is expected to be transferred through trusts, gifts, and wills. The share of farmland available for purchase by non-relatives during 2015-19 will likely rise above 2.3 percent as some individuals (or entities) that inherit land may choose to sell it. And, those who inherit land but don’t sell it may decide to rent it out to farm operators. In 2014, 39 percent of all farmland was rented and 61 percent was owned by farm operators. This chart comes from the ERS report U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer, released on August 25, 2016.

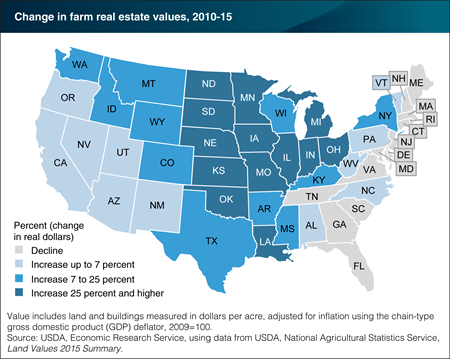

Wednesday, July 20, 2016

Between 2010 and 2015, change in inflation-adjusted average farm real estate values (the value of farmland and buildings) varied widely across the 48 contiguous States. The value of farm real estate is expected to change over time to reflect changes in expectations for income streams from future use—including both agriculture and nonagricultural uses. Over 2010-15, the largest State percentage increases in farm real estate values occurred in the Northern Plains and Midwest regions, presumably based on expectations of high farm-based earnings. In contrast, while farmland values in the Northeast region are typically among the highest in the country, this is largely due to urban proximity rather than agricultural returns, and declines in farm real estate values generally reflect regional impacts from the downturn in the residential housing market. This map is based on the data visualization, Charts and Maps of U.S. Farm Balance Sheet Data, in the Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, February 2016.

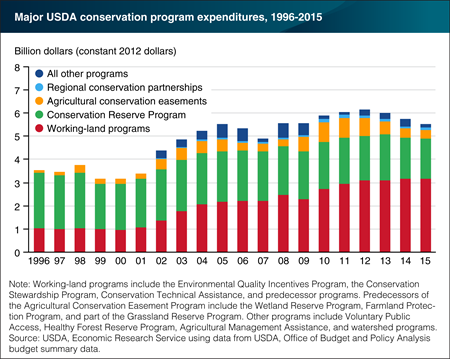

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

USDA relies mainly on voluntary programs providing financial and technical support to encourage farmers to conserve natural resources and protect the environment. In inflation adjusted terms, USDA conservation program expenditures increased by roughly 70 percent between 1996 and 2012. Much of the increases in real spending over this period occurred in working land programs and agricultural easements. Working land programs provide assistance to farmers who install or maintain conservation practices (such as nutrient management, conservation tillage, and the use of field-edge filter strips) on land in crop production and grazing. Agricultural easements provide long-term protection for agricultural land and wetlands. The Conservation Reserve Program—which pays farmers to remove environmentally sensitive land from production and encourages partial-field practices such as using grass waterways and riparian buffers—is still USDA’s largest conservation program, but has slowly ebbed in prominence. While real spending on USDA conservation programs rose under the 2002 Farm Act (2002-07) and the 2008 Farm Act (2008-13), the 2014 Farm Act reduced mandatory spending, and expenditures over 2014 and 2015 appear to be leveling off. This chart is found in the Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials data product on the ERS website.

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

The ERS Major Land Uses (MLU) data series provides a snapshot of land use across the United States. While much of the MLU series is updated roughly every 5 years, cropland used for crops, the category representing the acres of land in active crop production, is updated on an annual basis. Cropland used for crops has three main components: cropland harvested (including acreage double-cropped), crop failure, and cultivated summer fallow. In 2015 (the most recent estimate), the total area of cropland used for crops in the United States was 335 million acres, down 6 million acres from the 2014 estimate and about 5 percent below the 30-year average. In 2015, cropland harvested declined by 1 percent (3 million acres) over the previous year. The area that was double-cropped—land from which two or more crops were harvested—declined by 1 million acres, a 13-percent decline from the 2014 double-cropped area of 8 million acres. Acres on which crops failed declined by 30 percent over the past year to 7 million acres, the lowest level since 2010. This chart is based on ERS’s Major Land Uses, summary table 3: Cropland used for crops, updated March 25, 2016.

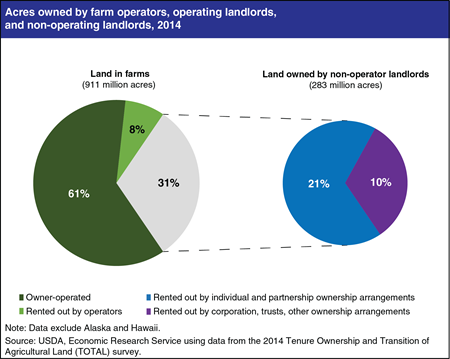

Monday, December 28, 2015

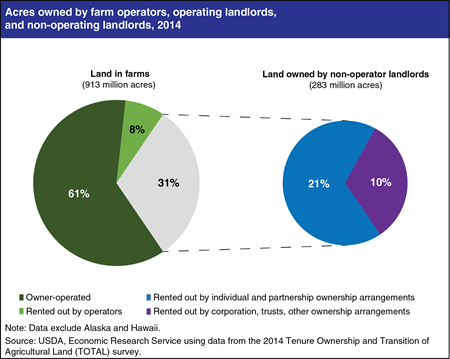

Of the 911 million acres of land in farms, 61 percent is operated by the land owner, according to the 2014 Tenure Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) survey. Another 8 percent (70 million acres) of land in farms is rented from other farm operators. The remaining land in farms (31 percent or 283 million acres) is rented from “non-operating landlords,” or landlord entities that are not currently farmer operators. The majority of acres owned by these non-operating landlords is held by individuals or in partnerships (191 million acres or 21 percent of land in farms). Corporations, trusts, or other ownership arrangements also rent out 92 million acres (about 10 percent of land in farms) to operators. Even though some agricultural land is owned by non-operating landlords, many of these landlords have prior farming experience. Of the 191 million acres owned in individual or partnership arrangements, nearly half were held by a retired farmer or rancher in 2014. Six percent of the acres owned in individual and partnership arrangements by non-operating landlord entities had a principal landlord that reported spending greater than 50 percent of their work time in farm or ranch work, but not as a farm operator. More information can be found on the ERS Land Use, Land Value & Tenure topic page.

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

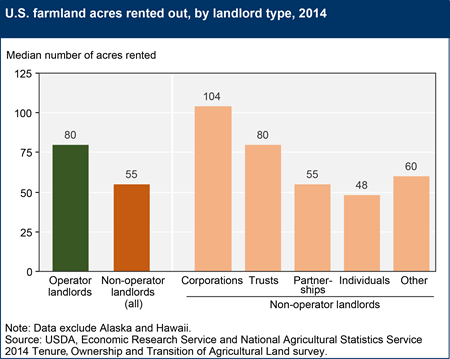

According to the Tenure, Ownership and Transition of Agriculture Land (TOTAL) survey, 354 million acres of farmland in the lower 48 States were rented to farmers by 2.13 million landlords in 2014. The average amount of land rented out per landlord yields insights into whether rented farmland is concentrated amongst particular types of landlords. Operator landlords—farm operators who rent land to other farmers—typically rented out more acreage than non-operator landlords. Among non-operator landlords, the acres held in corporate, trust, and other types of non-operator ownership arrangements are more concentrated (proportionately more land in fewer hands) than individual and partnership non-operator landlords. The median rented acreage for farmers who rent land from others was 111 acres in 2014—larger than the median acreage rented to farmers by each landlord type. This means that most farm operators looking to rent farmland must instead piece together holdings from multiple landlords. This chart is found in the November 2015 Amber Waves data feature, “Tenure, Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) Survey 2014: A New ERS/National Agricultural Statistics Service Data Product.”

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

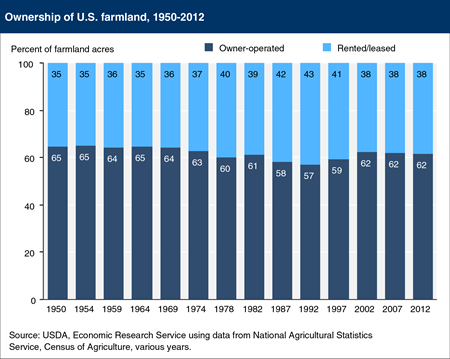

Because land is a critical input to farming and farm real estate represents such a large portion of the value of farm sector assets (around 80 percent), the ownership of agricultural land is a topic of interest to farmers, lenders, policymakers and others concerned with the farm sector. Issues surrounding production practices and conservation, farm credit, land values, farm succession, land use, and farm structure, all require an understanding of land ownership and tenure. A majority of U.S. land in farms (62 percent) is operator-owned, according to the 2012 Census of Agriculture. The balance of farmland is rented, and the portion of rented land in farms has ranged from 35 percent to 43 percent over the 1950-2012 time period. Some farmland is rented from other farm operations—nationally about 8 percent of all land in farms in 2012. The majority of rented land in farms is rented from nonoperating landlords. In 2012, 30 percent of all land in farms was rented from someone other than a farm operator. This chart is found on the ERS topic page, Land Use, Land Value & Tenure.

Thursday, September 3, 2015

The ERS Major Land Uses (MLU) series estimates land in various uses, including the acres devoted to crop production in a given year. These acres, collectively referred to as “cropland used for crops,” include acres of cropland harvested, acres on which crops failed, and cultivated summer fallow. In 2014 (the most recent estimate), the total area of cropland used for crops was 340 million acres, up 4 million acres from the 2013 estimate but in line with the 30-year average. In 2014, cropland harvested increased by 2 percent (6 million acres) over the previous year. The 317 million acres of cropland harvested represents the highest harvested acreage since 1997, when cropland harvested was 321 million acres. The area double cropped—land from which two or more crops were harvested—declined by 1 million acres, a 10 percent decline from the 2013 double-cropped area of 10 million acres. Acres on which crops failed declined by 25 percent over the past year to 9 million acres, the lowest level since 2010. Cultivated summer fallow, which primarily occurs as part of wheat rotations in the semiarid West, has remained relatively stable over the last 10 years, although its use has been declining since the late 1960s. Larger historical fluctuations seen in cropland used for crops are largely attributable to Federal cropland acreage reduction programs. This chart is based on ERS’s Major Land Uses, Summary table 3: Cropland used for crops, updated August 31, 2015 to include 2014 estimates.

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

Of the 911 million acres of land in farms in the continental U.S., 61 percent is operated by the land owner, according to the 2014 Tenure Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) survey. Another 8 percent (70 million acres) of land in farms is rented from other farm operators. The remaining land in farms (31 percent or 283 million acres) is rented from “non-operating landlords”, or landlord entities that are not currently farmer operators. The majority of acres owned by these non-operating landlords is held by individuals or in partnerships (191 million acres or 21 percent of land in farms). Corporations, trusts, or other ownership arrangements also rent out 92 million acres (about 10 percent of land in farms) to operators. Even though some agricultural land is owned by non-operating landlords, many of these landlords have prior farming experience. Of the 191 million acres owned in non-operator individual or partnership arrangements, nearly half were held by a retired farmer or rancher in 2014. About 6 percent of the acres owned in individual and partnership arrangements by non-operating landlord entities had a principal landlord that reported spending greater than 50 percent of their work time in farm or ranch work, but not as a farm operator. More information can be found on the ERS Farmland Ownership and Tenure topic page.

Friday, August 28, 2015

With a value of $2.38 trillion, farm real estate (land and structures) accounted for 81 percent of the total value of U.S. farm sector assets in 2014. Because it comprises such a significant portion of the U.S. farm sector’s asset base, change in the value of farm real estate is a critical barometer of the farm sector's financial performance. On average, U.S. (excluding Alaska and Hawaii) farm real estate values increased 2.4 percent (in nominal terms) to $3,020 per acre over the 12 months ending June 1, 2015. Growth in average values has slowed substantially relative to the previous three year mid-year to mid-year periods, when nominal farm real estate values increased over 8 percent annually. National averages mask wide regional variation. Based on nominal values, farm real estate in the Southern Plains and Pacific regions experienced the highest rates of appreciation of 6.1 percent and 5.8 percent (to $1,900 and $4,780 per acre), respectively, over the 12 months ending June 1, 2015. In contrast, farm real estate in the Corn Belt declined 0.3 percent (to $6,350 per acre). This chart is found on the ERS topic page on Land Use, Land Value & Tenure, updated August 2015.

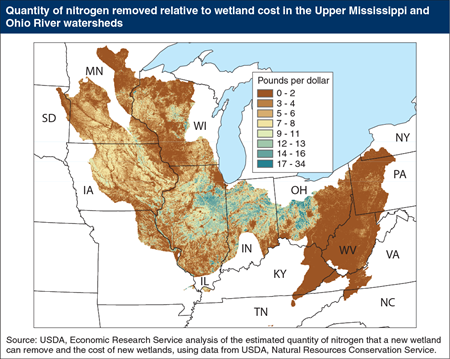

Monday, June 1, 2015

Every year, agriculture contributes an estimated 60-80 percent of delivered nitrogen and 49-60 percent of delivered phosphorous in the Gulf of Mexico. Nitrogen in waters can cause rapid and dense growth of algae and aquatic plants, leading to degradation in water quality as found in the hypoxic zone of the Gulf of Mexico, where excess nutrients have depleted oxygen needed to support marine life. Nitrogen removal is one of the many benefits of wetlands. An ERS analysis found that on an annual basis, the amount of nitrogen removed per dollar spent to restore and preserve a new wetland ranged from 0.15 to 34 pounds within the area of study (the Upper Mississippi/Ohio River watershed), or a range of $0.03 to $7.00 per pound of nitrogen removed. Restoring and protecting wetlands in the very productive corn-producing areas of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio tends to be more cost effective than elsewhere in the study area. The study suggests that if nitrogen reduction was the only environmental goal, these corn-producing areas would be a good place to restore wetlands. Hydrologic conditions in the Upper Mississippi and Ohio River watersheds are unique, so the cost effectiveness of wetlands elsewhere is uncertain. This map is found in the ERS report, Targeting Investments To Cost Effectively Restore and Protect Wetland Ecosystems: Some Economic Insights, ERR-183, February 2015.

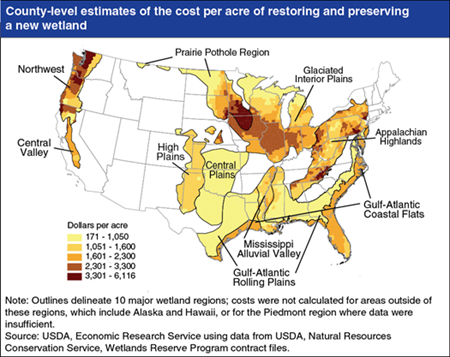

Friday, April 10, 2015

USDA’s costs of restoring and preserving new wetlands across the contiguous United States range from about $170 to $6,100 per acre, with some of the lowest costs in western North Dakota and eastern Montana and the highest in major corn-producing areas and western Washington and Oregon. To analyze conservation program expenditures, ERS researchers generated county-level estimates of wetland costs for each of the major wetland regions as designated by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (outlined in black in the map), using primarily NRCS Wetland Reserve Program contract data. Variations in costs are driven by differences in land values and the complexity of restoring hydrology and wetland ecosystems. Information about how the costs of restoring and preserving wetlands vary spatially (together with the relative benefits) can inform wetland targeting policies within States/regions and across the U.S. This map is found in the ERS report, Targeting Investments to Cost Effectively Restore and Protect Wetland Ecosystems: Some Economic Insights, ERR-183, February 2015.