ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Wednesday, March 20, 2024

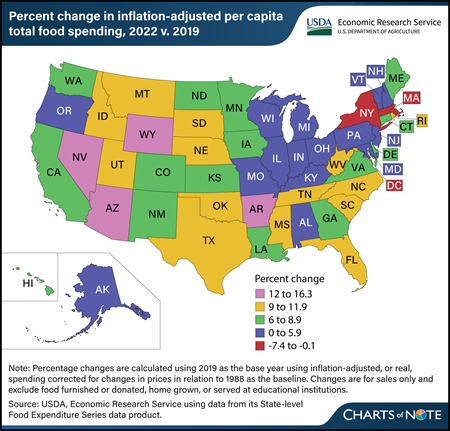

The U.S. food system experienced many changes since 2019, particularly during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Per capita total U.S. food spending increased 6.3 percent in 2022 compared with 2019 when adjusted for inflation. Inflation-adjusted food-at-home spending approached 2019 levels in 2022, while food-away-from-home spending remained high compared with prepandemic levels. However, this trend was not consistent across States. Washington, DC, had the largest decrease in total food spending between 2019 and 2022 (7.4 percent), mainly driven by a 12.9-percent decline in food-away-from-home spending. States with decreases or relatively small increases in total food spending were largely concentrated in the Northeast. Massachusetts and New York each saw decreases of 0.7 percent in inflation-adjusted, per capita total food spending between 2019 and 2022, while food spending in Vermont grew 1.6 percent. Many States with the largest increases in inflation-adjusted, per-capita food spending were concentrated in the West, with Nevada (16.3 percent), Wyoming (15.5 percent), and Arizona (13.9 percent) seeing the largest increases over the period. This chart is drawn from USDA, Economic Research Service’s State-level Food Expenditure Series, updated February 2024. For more on food spending, see the Amber Waves article U.S. Consumers Spent More on Food in 2022 Than Ever Before Even After Adjusting for Inflation, published September 2023.

Monday, January 22, 2024

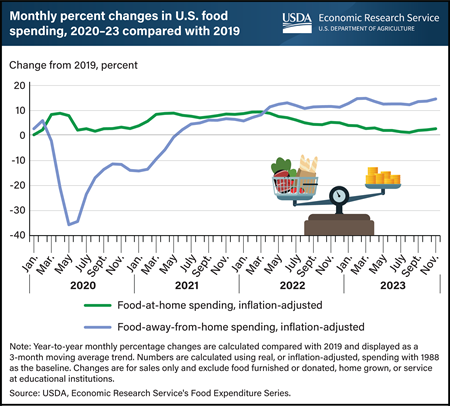

Following shifts in U.S. food spending during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, food-at-home (FAH) spending was only 2.7 percent higher in November 2023 compared with November 2019, while food-away-from-home (FAFH) spending remained elevated at 14.6 percent higher. After an initial jump in inflation-adjusted FAH spending in March through May 2020, FAH spending leveled off, averaging just 2.8 percent higher in December 2020 compared with 2019. Even as FAH prices increased throughout 2021 and 2022, inflation-adjusted FAH spending increased as well, with monthly FAH spending in these years averaging 7.2 percent higher than the corresponding months in 2019. FAH spending has trended back toward prepandemic levels since the peak difference of 9.5 percent in March 2022. By contrast, FAFH spending initially fell significantly during the pandemic but reversed quickly and outpaced 2019 spending starting in June 2021. From June 2021 through December 2022, monthly inflation-adjusted FAFH spending averaged 8.7 percent higher than the corresponding months in 2019. FAFH spending peaked at 14.8 percent higher in March 2023 compared with March 2019. This chart combines and updates two charts from USDA, Economic Research Service’s (ERS) Amber Waves article U.S. Consumers Spent More on Food in 2022 Than Ever Before, Even After Adjusting for Inflation using data from the ERS Food Expenditure Series data product, updated January 19, 2024.

Monday, August 14, 2023

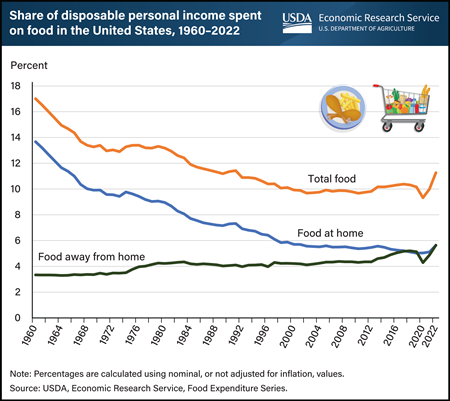

Errata: On August 16, this chart was updated with the correct year for when a similar level of income was previously spent on food. No other data were affected.U.S. consumers spent an average of 11.3 percent of their disposable personal income (DPI) on food in 2022, a level not observed since 1991. DPI is the amount of money U.S. consumers have left to spend or save after paying taxes. Consumers spent 5.62 percent of their incomes on food at supermarkets, convenience stores, warehouse club stores, supercenters, and other retailers (food at home) in 2022 and 5.64 percent on food at restaurants, fast-food establishments, schools, and other places offering food away from home. In 2022, the share of DPI spent on total food had the sharpest annual increase (12.7 percent). This followed an 8.2-percent decline, the sharpest annual drop in total food spending since 1967, during the first year of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020. The recent volatility in spending was driven by consumers’ sudden drop in eating out at the beginning of the pandemic followed by a return to food-away-from-home purchases as pandemic-related restrictions and concerns eased. The chart is drawn from USDA, Economic Research Service’s Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials and Food Expenditure Series data product, updated July 2023.

Monday, July 17, 2023

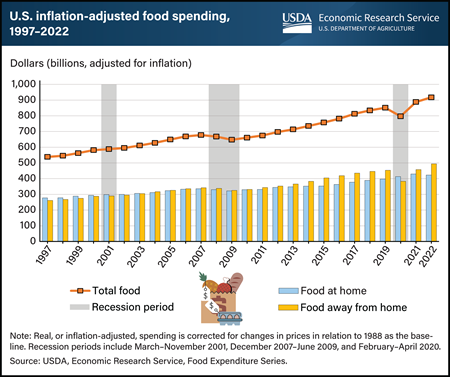

Real, or inflation-adjusted, annual food spending in the United States increased steadily from 1997 to 2022, except in 2008 and 2009 during the Great Recession and in 2020 during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Food spending includes food at home (FAH), described as food intended for off-premises consumption from retailers such as grocery stores, and food away from home (FAFH), described as food purchased at outlets such as restaurants or cafeterias. Total food spending increased 70 percent from 1997 to 2022. During this period, FAH spending increased at a slower rate (53 percent) than for FAFH (89 percent). Total food spending increased on an annual basis by 7.2 percent in 2021 and 4.5 percent in 2022. FAFH spending increases (19 percent in 2021 and 8 percent in 2022) drove overall increases in food spending. FAH spending increased by 4 percent in 2021 but fell by 2 percent in 2022. The data for this chart come from the USDA Economic Research Service’s Food Expenditure Series data product, updated in June 2023.

-FAH-Spending-by-Race_450px.png?v=9802.7)

Monday, July 10, 2023

U.S. households shifted away from buying foods at restaurants and other food service venues to food-at-home (FAH) outlets such as grocery stores and other retail establishments in 2020. The largest FAH shifts came from a category designated by USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) as “all other FAH,” which includes prepared meals and salads, desserts, and foods not elsewhere classified such as soups, savory snacks, candy, sweeteners, margarine, and butter. “All other FAH” was by far the largest FAH category before 2020, and its share of the household food budget increased by 2.6 percentage points in 2020 compared with the period from 2016 to 2019. However, this increase was unevenly distributed across racial and ethnic populations and among subcategories within “all other FAH.” All U.S. racial and ethnic subpopulations except Hispanic households increased their total food budget share for “all other FAH” during this period. Black households increased their budget shares for “all other FAH” the most, followed by Asian households. The increase by Asian households on “all other FAH” was driven by a 1.6-percentage-point rise in prepared meals and salads and a 1.8-percentage-point increase in other, not elsewhere classified foods, such as snacks. In contrast, Black households had a larger increase in other, not elsewhere classified foods (2.0 percentage points) and desserts (1.4 percentage points). This chart appears in the ERS Amber Waves article, New Analysis Approach Illuminates Differences in Food Spending Across U.S. Populations, published in May 2023.

Monday, June 5, 2023

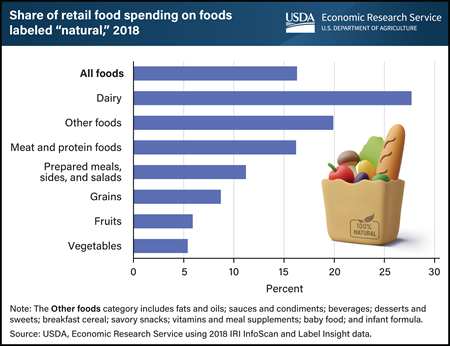

In 2018, food products labeled “natural” accounted for slightly more than 16 percent of all consumer retail food purchases. USDA and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration require producers to adhere to specific standards or processes to use certain label claims, such as USDA Organic. The “natural” claim, however, has minimal requirements and using the claim on a food product’s packaging does not require that the product provide any health or environmental benefits. Regulatory agencies treat the claim as meaning nothing artificial was added and the product was minimally processed. Even so, consumers sometimes attribute benefits to products labeled “natural,” research studies show. The share of products labeled “natural” varies by food category. The share of spending on “natural” products in 2018 was highest for dairy products (27.7 percent) and lowest for fruits (5.9 percent) and vegetables (5.4 percent). The data in this chart appear in the USDA, Economic Research Service report The Prevalence of the “Natural” Claim on Food Product Packaging, published in May 2023.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

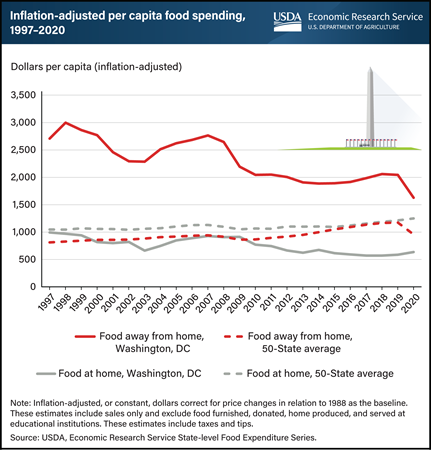

Food spending estimates for Washington, DC, differ widely from the 50-State average estimates. From 1997 to 2020, Washington, DC, had higher inflation-adjusted per capita sales at food-away-from-home (FAFH) establishments, such as restaurants, than the State average, although the gap narrowed over time. In 1997, FAFH spending in Washington, DC, was more than 3 times the 50-State average and 1.7 times the 50-State average in 2019 and 2020. The difference could be attributed to nonresident workers commuting into Washington, DC, and spending more at FAFH establishments. FAFH spending per capita in 2019 was 24 percent higher in Washington, DC, than in the highest State (Hawaii). Meanwhile, sales at food-at-home (FAH) outlets, such as grocery stores and supercenters, across the 50 States have steadily increased, with an average annual growth rate of 0.8 percent since 1997. However, FAH spending in Washington, DC, has been more volatile and has trended downward over time. Inflation-adjusted per capita spending on FAH in Washington, DC, was 40.8 percent lower in 2019 than in 1997, before increasing 8.2 percent in 2020 during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. FAH spending in Washington, DC, was roughly equal to the 50-State average in 1997 but fell to approximately half the average from 2017 to 2020. FAH spending per capita in Washington, DC, in 2019 was 37 percent lower than the lowest State (Arkansas). This chart is drawn from the USDA, Economic Research Service’s State-level Food Expenditure Series, which launched in May 2023 and provides annual data on food spending for each State and Washington, DC, from 1997 to 2020.

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

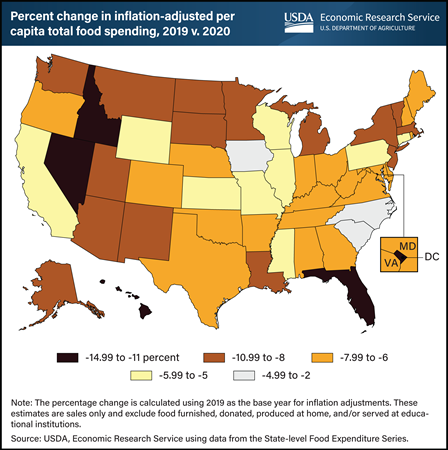

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States disrupted the food industry in 2020. Inflation-adjusted total U.S. food expenditures were 6.6 percent lower in 2020 than in 2019. However, individual States experienced varying degrees of food spending decline during this period. The USDA, Economic Research Service’s (ERS) newly developed State-level Food Expenditure Series helps to illustrate annual food spending changes across States since 1997, including Washington, DC. From 2019 to 2020, each State saw decreases in inflation-adjusted, per capita total food spending. The smallest decreases in food spending were in Iowa (2.2 percent), South Carolina (2.6 percent), and North Carolina (4.1 percent). The States that saw the largest decreases in inflation-adjusted, per-capita food spending were Hawaii (15 percent), Washington, DC (13.9 percent), Florida (11.8 percent), and Nevada (11.6 percent). These States typically have large out-of-State population inflows from nonresident workers and tourists. The median change of total food spending occurred in Delaware, with a decrease of 7.2 percent. These spending changes occurred as health concerns and mobility restrictions during the first year of the pandemic led consumers to spend less at restaurants and other eating out establishments in favor of relative cost-efficient outlets, such as grocery stores and supercenters. This chart is drawn from ERS’ State-level Food Expenditure Series, which launched in May 2023 and provides annual data on food spending for each State and Washington, DC, from 1997 to 2020.

-Market-Concentration-by-Area_450px.png?v=9802.7)

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

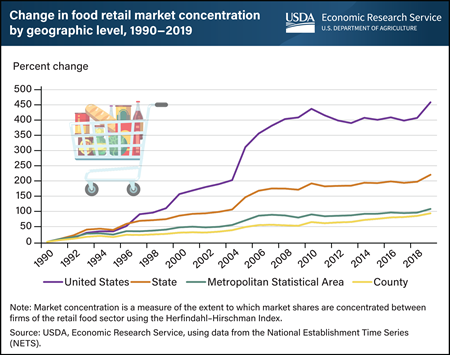

The food retail market comprises individual firms, such as grocery stores and supercenters, that sell food products to consumers. The concentration of these retailers’ shares of the market, as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), increased over the last three decades at the national, State, Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), and county levels in the United States. HHI values range from 0 to 10,000, with higher values reflecting higher levels of market concentration, fewer firms, or increasing disparity between the size of the firms in the market. On average, food retail concentration is higher at the MSA level than at the national level, and concentration is even higher once the market is defined at the county level. As the geographic market area shrinks, the market concentration in 2019 increased from 593 (national) to 1,332 (State) to 1,881 (MSA) to 3,737 (county). Trends in localized markets are likely most relevant for consumers, food-retail competitors, and policymakers. This chart appeared in the USDA, Economic Research Service report A Disaggregated View of Market Concentration in the Food Retail Industry, which uses data from the National Establishment Time Series (NETS) to calculate and examine the market conditions of food retailing from 1990 to 2019.

-FAFH-monthly-outlets_450px.png?v=9802.7)

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

In April 2020, as effects of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the U.S. economy unfolded, spending at full-service restaurants declined 71 percent compared with April 2019. Spending at limited-service—or fast-food—restaurants fell 32 percent, and spending at all other food-away-from-home establishments, such as drinking places, hotels, and motels, dropped 41 percent over the same period. Full-service restaurants typically offer food and alcohol to seated customers who pay after eating and include amenities such as ceramic dishware and non-disposable utensils. Limited-service restaurants prioritize convenience and have limited menus, sparse dining amenities, and no waitstaff. The limited physical interaction with customers made it easier for fast-food establishments to adapt to COVID-19 restrictions, and by the second half of 2020, they managed to recover to pre-pandemic spending levels. Despite efforts by many full-service restaurants to expand takeout and delivery services, these outlets took slightly longer to bounce back, and returned to pre-pandemic spending in March 2021. By December 2021, both full-service and limited-service restaurant spending had fully recovered and were each about 10 percent higher than in December 2019. The data for this chart were first included in the USDA, Economic Research Service’s Food Expenditure Series data product in February 2023 and will be updated with 2022 data in June 2023.

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

The U.S. food retail sector experienced substantial consolidation and structural change over the last three decades. Market concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), is a measure of the extent to which market shares are concentrated between firms of the retail food sector at the national, State, Metropolitan Statistical Area, and county levels in the United States. This analysis includes all establishments with a significant portion of food sales that are likely substitutes for each other: supermarkets and other grocery (except convenience) and warehouse clubs and supercenters. Although the national market is less concentrated than the average State level, according to the HHI, national market concentration increased substantially between 1990 and 2019 (458 percent). In comparison, average county-level market concentration has remained relatively constant over the past 30 years, increasing only 94 percent. While national measures provide information about larger trends, trends in localized markets are likely more relevant for consumers, food-retail competitors, and policymakers. This chart was drawn from the USDA, Economic Research Service economic research report A Disaggregated View of Market Concentration in the Food Retail Industry, which uses data from the National Establishment Time Series (NETS) to calculate and examine the market conditions of food retailing from 1990 to 2019. The report published in January 2023.

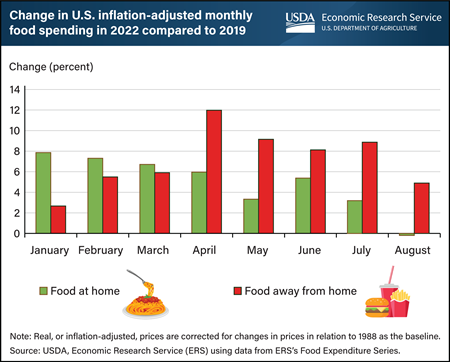

Friday, October 21, 2022

Real, or inflation-adjusted, monthly food spending in the United States has increased in 2022 as compared to the same period in 2019, before the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Inflation-adjusted food spending measures the quantity of food spending after removing price increase effects. Real monthly food at home (FAH) spending, or food intended for off-premise consumption from retailers such as grocery stores, increased each month through August 2022 as compared to 2019 except in August, with the highest increase in January at almost 8 percent. This increase may be the result of U.S. consumers purchasing more foods or choosing more expensive grocery store options, such as pre-cut vegetables and fruits, imported out-of-season foods, organic products, and prepared dishes, than they did in 2019. Real monthly food away from home (FAFH) spending, or food consumed at outlets such as restaurants or cafeterias, also increased each month so far in 2022, with the highest increase in April at 12 percent. Similarly, the increase seen in 2022 in real FAFH spending may be the result of U.S. consumers purchasing more FAFH in general or shifting toward more expensive options, such as foods at full-service restaurants. The data for this chart come from the ERS’s Food Expenditure Series data product.

_450px.png?v=9802.7)

Thursday, August 4, 2022

The share of U.S. consumers’ disposable personal income (DPI) spent on food was relatively steady from 2000 to 2019, rising from 9.93 percent in 2000 to 10.27 percent in 2019. DPI is the amount of money that U.S. consumers have left to spend or save after paying taxes. During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the share of income spent on food dropped to a new low of 9.4 percent in 2020. Food spending rebounded in 2021, however, and the share of income spent on food jumped to 10.27 percent, equaling the share in 2019. Between 2000 and 2019, consumer spending trended toward food away from home (restaurants, fast-food places, schools, and other dining establishments). From 2019 to 2020, this trend reversed as consumers spent more of their incomes on food at supermarkets, convenience stores, warehouse club stores, supercenters, and other retailers (food at home). As COVID-19 vaccines were distributed and many mobility restrictions were lifted in 2021, the share of food-away-from-home spending bounced back to just shy of the food-at-home spending share, signaling a return towards pre-pandemic spending trends. The data for this chart come from the USDA, Economic Research Service’s Food Expenditure Series data product.

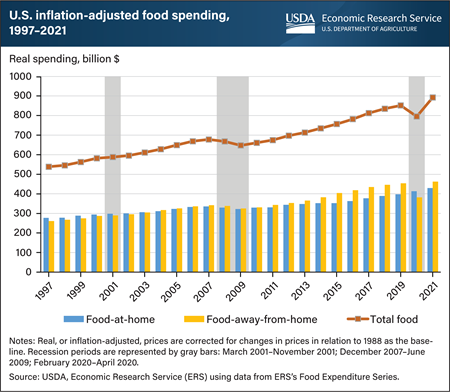

Monday, June 13, 2022

Real, or inflation-adjusted, annual food spending in the United States has increased every year since 1997 except in 2008, 2009, and 2020. Sales increased from 1997 to 2019 for both food at home (FAH), food intended for off-premise consumption from retailers such as grocery stores, and food away from home (FAFH), food consumed at outlets such as restaurants or cafeterias. Over this period, real FAH spending increased at a slower rate (43.5 percent) than for FAFH (73.9 percent). In 2020, during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, real total food expenditures fell 6.6 percent from 2019. U.S. consumers’ food-spending patterns changed as efforts were made to limit the spread of COVID-19, which included stay-at-home orders. FAFH spending decreased by 15.8 percent in 2020, while FAH spending increased by 3.9 percent. In 2021, real total food expenditures increased 12.2 percent from 2020. With increased household income during the economic recovery and relaxed safety measures around indoor dining and social distancing, FAFH spending increased by 21.1 percent in 2021 from the previous year and was the primary driver of the overall food spending increase. FAH spending increased by 4 percent. The data for this chart come from the ERS’s Food Expenditure Series data product.

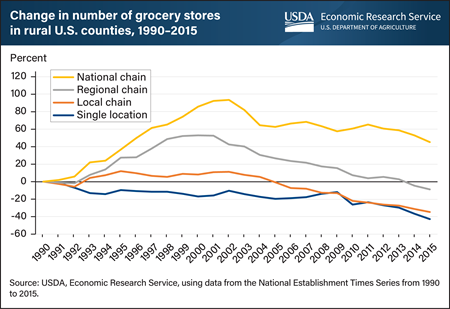

Friday, December 3, 2021

From 1990 to 2015, rural U.S. counties saw a noticeable change in the numbers and types of food retailers serving consumers, according to a recent USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) report. Researchers separated grocery stores—the most common type of food retailer—into four categories: single location, local chain, regional chain, and national chain. In rural counties, national chains were the only grocery stores that increased in numbers over the 25 years, rising by 45.2 percent. While single location grocery stores outnumbered the three other types in rural counties, they demonstrated the deepest decline with a 42.7 percent drop. The sharpest decline happened after 2009. The reduction in the number of single location stores drove an overall decline in the total number of grocery stores. Local chains decreased by 34.7 percent, and regional chains by 8.9 percent. This chart appears in the ERS report The Food Retail Landscape Across Rural America, released June 2021.

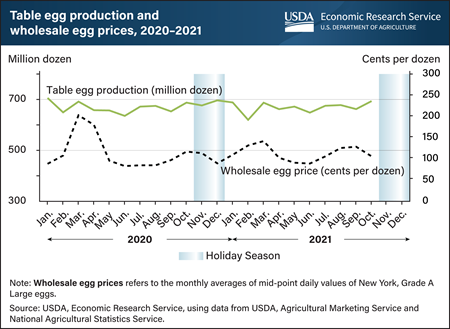

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Demand for table eggs tends to increase when holiday gatherings and cold weather encourage home baking and cooking. In accordance, wholesale table egg prices—the prices retailers pay to producers for eggs—tend to increase ahead of holidays such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter. Leading up to the 2021 holiday season, however, wholesale prices of table eggs in the United States have fallen as effects of Coronavirus (COVID-19)-linked flock adjustments linger. In normal years, producers anticipate seasonal demand by adjusting the size of the table-egg laying flocks and the rate at which they produce eggs. In 2020, COVID-19-related disruptions in the demand for eggs led producers to reduce flock sizes. Flock sizes have slowly rebuilt since the summer of 2020 but remain smaller than the same time in 2019. However, the younger flocks produce more eggs per hen. The higher productivity can offset the effects of the small flock size and support increased production. At the beginning of October 2021 the size of the U.S. laying flock was just above the October 2020 levels and the rate of lay was 1.1 percent higher. This productivity bump is predicted to support about a 1 percent increase in October 2021 table egg production compared with a year ago, leading to a 9.6 percent price reduction compared to October 2020. This chart is drawn from the USDA, Economic Research Service Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Monthly Outlook, published November 2021.

Monday, August 16, 2021

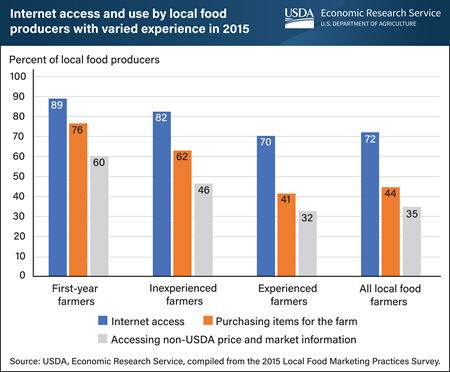

Local food producers had high levels of internet access in 2015 according to a recently released report by USDA, Economic Research Service researchers. They found that 72 percent of local food producers had internet access, either at the farm or at the principal farm operator’s residence. A local food producer is defined as a farming operation that produces and sells edible agricultural products directly to consumers, retailers, institutions, or intermediate markets. Geographic proximity of local food producers to urban areas may account for high levels of internet access. Less-experienced local food producers had greater internet access than those with more farming experience. Eighty-nine percent of first-year farmers had internet access, compared with 82 percent of inexperienced farmers (2 to 10 years of farming experience) and 70 percent of experienced farmers (more than 10 years of farming experience). In 2015, the most popular use of the internet by all local food producers was to buy items for the farm (44 percent of producers), including input supplies, commodities, and equipment. A larger share of first-year farmers used the internet to buy farm inputs (76 percent) and access price and market information from non-USDA sources (60 percent), followed by inexperienced farmers (62 percent and 46 percent, respectively) and experienced farmers (41 percent and 32 percent, respectively). This information is drawn from the ERS report, “Marketing Practices and Financial Performance of Local Food Producers: A Comparison of Beginning and Experienced Farmers,” released August 10, 2021.

Friday, August 13, 2021

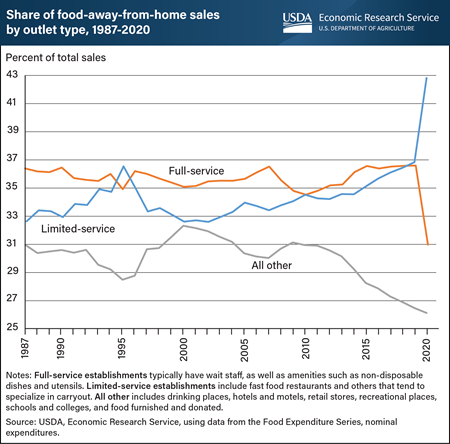

Full-service and limited-service restaurants (fast food restaurants)—the two largest segments of the commercial foodservice market—accounted for 70 percent of all food-away-from-home (FAFH) spending on average from 1987 to 2020. Consumers spent the other 30 percent at places such as hotels and schools. Full-service restaurants had the highest share of FAFH sales in every year of that period except 1995, 2010, 2019, and 2020. In 2020, the share of sales at full-service restaurants dropped from 36.5 percent in 2019 to 31 percent, resulting from a 29.4 percent decline in sales, partly because of safety closures during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Full-service establishments typically have wait staff and other amenities such as ceramic dishware, non-disposable utensils, and alcohol service. In contrast, limited-service restaurants, use convenience as a selling point; they have no wait staff, menus tend to be smaller, and dining amenities are relatively sparse. Given their minimal physical interactions with customers, fast food restaurants adapted to COVID-19 restrictions more quickly during 2020 and assumed a larger share of total FAFH sales at 42.7 percent, compared with 36.8 percent in 2019. Despite the increase in the relative share of FAFH sales, fast food sales decreased by 3.6 percent in 2020 compared with 2019. All other FAFH establishments, such as school and college cafeterias, reported a 17.9 percent decline in sales in 2020 and accounted for 26.3 percent of total FAFH sales. This chart appears on the USDA, Economic Research Service’s Market Segments topic page and its data come from the Food Expenditure Series data product.

Wednesday, August 4, 2021

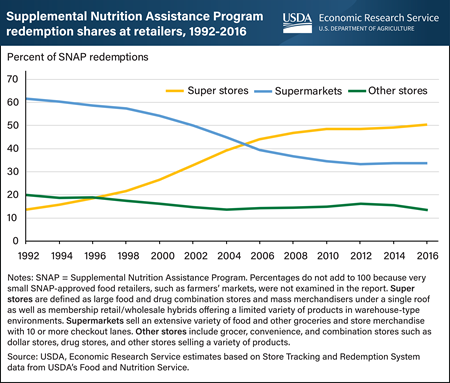

Since 2006, super stores received more USDA, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) redemptions than any other type of store, totaling half of all redemptions in 2016. SNAP participants can redeem benefits to buy food items at super stores, supermarkets, grocery stores, and other types of approved food retailers. Super stores are defined as large food and drug combination stores and mass merchandisers under a single roof as well as membership retail/wholesale hybrids offering a limited variety of products in warehouse-type environments. USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) researchers examined the effects of entrant super stores on the survival of existing SNAP-approved stores and their revenue from redeemed benefits. Researchers found that when one super store entered a market area from 1994 to 2015, about 0.25 supermarkets and 0.05 other smaller food retailers on average left over the first three years after entry. Overall store availability did not decline though, as the entry of one super store more than offset the loss of supermarkets and other smaller food retailers in the markets. The ERS researchers estimated that from 1994 to 2005, local supermarkets and other smaller food retailers annually lost $191,000 on average in SNAP redemptions for each super store entrant into their local market. That loss increased to $213,000 on average from 2005–15. At the same time, super stores gained much more in SNAP redemptions than was lost at local food retailers, leading the researchers to conclude that SNAP beneficiaries shifted purchases to super stores. Based on previous research showing that food is about 3 percent less costly at super stores, the researchers estimated that a shift of SNAP redemptions to super stores expanded the purchasing power of SNAP participants’ benefits by $108.6 million in 2015 (0.15 percent of total SNAP benefits and costs in 2015).This chart appears in the ERS’ Amber Waves article, “New Super Stores Slightly Expanded Purchasing Power for Participants in USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” June 2021.

Friday, July 2, 2021

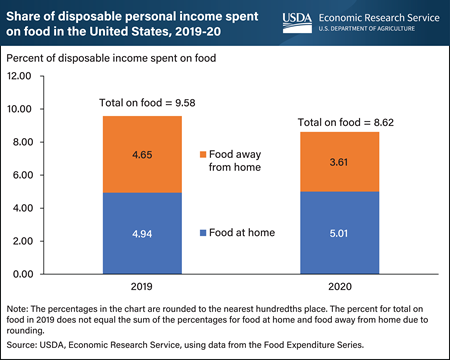

During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and economic recession in 2020, the share of U.S. consumers’ disposable personal income (DPI) spent on food decreased 10.1 percent from the previous year to 8.62 percent, the lowest share in the past 60 years. DPI is the amount of money that U.S. consumers have left to spend or save after paying taxes. The share of DPI spent on food in the United States was relatively steady over the last 20 years, decreasing from 9.95 percent in 2000 to 9.58 percent in 2019. Consumers spent 1.4 percent more of their incomes on food at supermarkets, convenience stores, warehouse club stores, supercenters, and other retailers (food at home) from 2019 to 2020, while they spent 22.2 percent less of their incomes on food at restaurants, fast-food places, schools, and other places offering food away from home over the same period. Changes in the shares of income spent on food in 2020 resulted, in part, from pandemic-related closures and restrictions at food-away-from-home establishments, as well as from the largest annual DPI increase in 20 years. The increase in DPI was driven by additional Government assistance to individuals in 2020, including stimulus payments to households and increased unemployment insurance benefits. The data for this chart come from the Economic Research Service’s Food Expenditure Series data product. See also the Amber Waves article Average Share of Income Spent on Food in the United States Remained Relatively Steady from 2000 to 2019, published in November 2020.