Child Poverty Heavily Concentrated in Rural Mississippi, Even More So Than Before the Great Recession

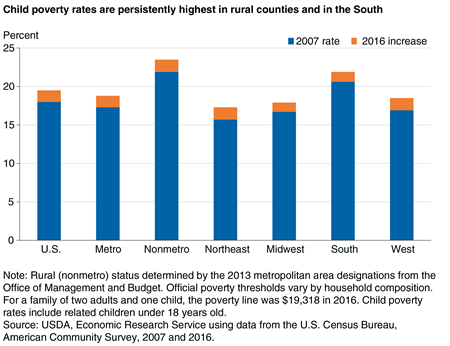

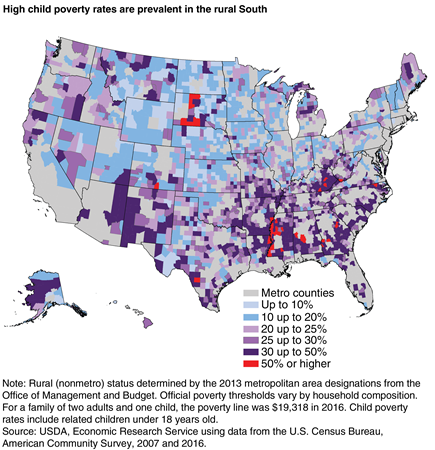

The share of children living in poverty in the U.S. remains higher than it was before the Great Recession. According to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), nearly 20 percent of children were living in poverty in 2016, compared with 18 percent in 2007. Also, the number of children in poverty increased over this period by 1 million, from 13,097,100 to 14,115,713. Child poverty rates continue to be highest in the South and Southwest, particularly in counties with concentrations of Native Americans and along the Mississippi Delta. Children in poverty tend to live in rural (nonmetro) counties—many with persistently high poverty—that were hard hit by the recession.

In 2016, 23.5 percent of rural children were poor, compared with 20.5 of urban (metro) children. Rural child poverty remained higher than pre-recession rates nearly a decade after the Great Recession (2007-09). That was also true of child poverty in urban areas and within all regions of the Nation.

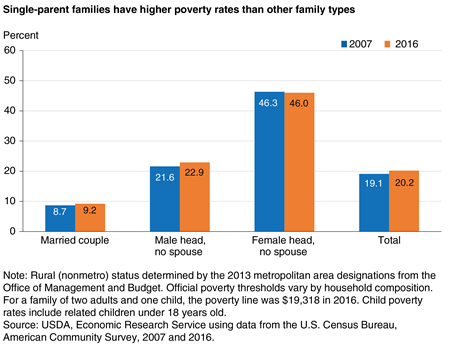

Research has linked poverty to low levels of well-being in childhood and adulthood, including health, economic, and behavioral problems. These problems can often drive increases in individual and family poverty over time. Child poverty is more sensitive to labor market conditions than is overall poverty. Scarcity of jobs, physical isolation, and lack of employment and transportation services often pose earnings challenges for rural parents, putting their children at risk of being poor. That risk is greatest among single-parent families, particularly those headed by a female. Research shows that among family types, single parents are less likely to have an education beyond high school and are more likely to be without employment or to work in a job that is not secure or does not pay a living wage.

In 2016, rural female-headed families with no spouse present made up 26 percent of all rural families with children and 60 percent of all rural families with children that were poor. The poverty rate for rural female-headed families was 46 percent, compared with about 23 percent for rural male-headed (no spouse) families and 9 percent for rural married-couple families with children. These rates were nearly unchanged from 2007, indicating the persistently high likelihood of living in poverty for rural children in single-parent families.

The number of children living in poor areas, regardless of their family economic standing, has risen over time. The share of all rural children residing in high child poverty counties (child poverty rate of 20 percent or more) was nearly 2 percentage points greater in 2016 than in 2007. That increase was almost entirely among nonpoor children. In total, about three of five nonpoor rural children and four of five poor rural children lived in high child poverty counties in 2016. Research has shown that growing up in poor areas increases the likelihood that children may experience the consequences of poverty, such as lack of access to healthy food, healthcare, quality education, and adequate housing. Furthermore, that exposure to areas with concentrations of extreme and persistent poverty increases their risk of negative outcomes.

Rural child poverty concentrated and persistent in the South

Overall, 56 percent of all 3,142 U.S. counties had high child poverty rates in 2016. That included about 61 percent of all 1,976 rural counties and 86 percent of the 830 rural counties in the South. Extreme child poverty (child poverty rate of 50 percent or higher) existed in 41 of the high child poverty counties in 2016, of which 38 were rural counties almost entirely in the South (31 in the South, 6 in the Midwest, and 1 in the West). The highest rural child poverty rates were in Mellette County, South Dakota (about 71 percent); Issaquena County, Mississippi (69 percent); and East Carroll Parish, Louisiana (68 percent). Furthermore, 13 of the rural counties with extreme child poverty were in Mississippi, mainly along the Mississippi Delta region. Eight of these counties had extreme child poverty prior to the recession, and the remaining five moved from high child poverty before the recession to extreme child poverty at present.

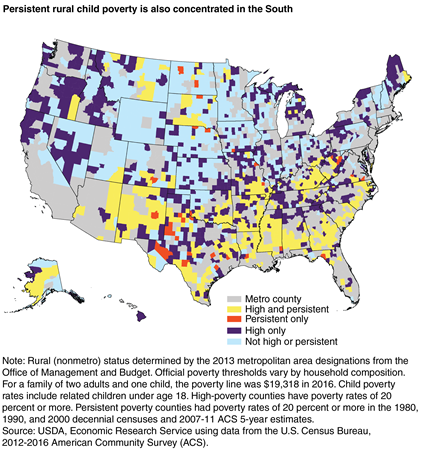

Many high child poverty counties in rural areas had concentrations of poor racial/ethnic minorities, such as African-American populations in the Mississippi Delta and Native Americans on tribal lands. High child poverty counties made up of predominantly White populations were found mainly in central Appalachia. The difference between rural counties with high child poverty and rural counties without high child poverty can largely be characterized by the prevalence of single-parent families and young adult high school dropout rates, and the extent to which these factors co-exist. For most high child poverty counties, these characteristics did not arise as a result of the 2007-09 economic recession but rather from long-term economic distress that limits economic opportunity and investment in education. This is reflected in persistently high poverty rates over multiple decades. However, as with past recessions, the most recent recession exacerbated these conditions, making it harder for vulnerable populations to recover.

Persistent child poverty counties are defined as those with poverty rates of 20 percent or more over the last 30 years (measured by the 1980, 1990, and 2000 decennial censuses and 2007-11 American Community Survey 5-year estimates). Persistent poverty tends to be a rural county phenomenon that is often tied to physical isolation, exploitation of resources, limited assets and economic opportunities, and an overall lack of human and social capital. There are currently 708 persistent child poverty counties (23 percent of all U.S. counties), and they are disproportionally rural. About 79 percent (558 counties) of persistent child poverty counties are in rural areas. Among all rural counties, 27 percent (523 counties) had persistently high child poverty up until the Great Recession and continued to have high child poverty in 2016. Another 38 percent (673 counties) had high child poverty in 2016 but not persistently high child poverty. Rural counties in the South accounted for 80 percent of the former group (416 counties), and 44 percent (299 counties) of the latter group.

Nationwide, Mississippi had the greatest concentration of rural child poverty in 2016. Rural counties make up nearly 80 percent of the 82 counties in Mississippi. Among these rural Mississippi counties, 82 percent (53 counties) were persistently poor and continued to have high child poverty in 2016. Another 17 percent (11 counties) had high child poverty in 2016 but not persistently high child poverty. Nearly all rural Mississippi counties had child poverty rates of 20 percent or more in 2016, including those that did not have high child poverty prior to the Great Recession. By comparison, 65 percent of all rural counties and 56 percent of all U.S. counties had child poverty rates of 20 percent or more in 2016.

Rural Poverty & Well-Being, by Tracey Farrigan, USDA, Economic Research Service, November 2023

Understanding the Rise in Rural Child Poverty, 2003-14, by Thomas Hertz and Tracey Farrigan, ERS, May 2016